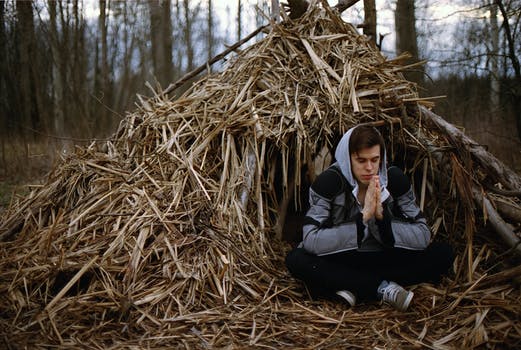

Being able to meditate in solitude is fine. Being able to meditate in a crowd is bliss.

One of the fundamental practices which constitutes a foundation of any successful magician’s toolkit is meditation. In his seminal work, Sorcerer’s Secrets, professional sorcerer Jason Miller advocates the incorporation of meditation techniques within basic daily routines. Similarly, the topic of meditation is one that arises quite frequently among pagans, witches, druids, Thelemites and those who practice magic, and with good reason. In our interview with traditional witchcraft magister, Stuart Inman similarly indicates the one of the fundamental practices we can incorporate, and which can be beneficial, is mindfulness:

I do think that the basic practice of mindfulness is very useful for anybody, even in its modern, secular and rather sanitized version, as long as it is not too resolutely corporate, and many modern pagans could do with that, or else a kick up the arse, or possibly both.

Indeed, as practicing pagans, or simply as individuals with a secular worldview and a desire to attain a profound sense of peace, there are few alternatives to meditation. Whilst there are many methods to attain altered states of consciousness, precious few can achieve this at will and with an element of control, as well as our involvement and engagement.

Within glib works which passingly refer to meditation practices fleetingly, with a casual mention that it is something one should do, while deferring to Buddhist or alternative spiritual authorities, we can not be expected to aspire to any proficiency of application. However, many writings do make mention of altered states of consciousness, as though these abstract doors of perception are the grail itself, whilst furnishing the reader with limited, confusing and often confused concepts.

Without professing to any proficiency myself, nor with any credible authority upon the subject, there are a few key things that I have learnt over the years which may be of use to others.

What are we practicing for?

Firstly, it is necessary to understand that meditation is a practice, that is it is something we do. The elusive Eastern concept of Nirvana, that bliss of pure consciousness without thought, oneness with the universe and a cessation of the chattering monkey mind, should not be the goal here. Any Eastern teacher worth their salt will tell you that meditation itself is the goal and practice, object and subject being one.

To unpack that previous paragraph a little, we need to consider what we mean by a practice. The Oxford English Dictionary online has this definition:

Practice: The actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method, as opposed to theories relating to it.

So we can see immediately that we are not using practice to indicate a rehearsal, or something that which requires an ending or final performance. Indeed, meditation is a practice with the end in and of itself; it is something we do. The transcendental state of Nirvana, a release from suffering and desire, sublimation of the ego self, may be attained through the practice of meditation but it should not be the aim. Indeed, one might contest that the person who meditates to experience the bliss of Nirvana will never achieve it. This could be because the ego which aspires to that heightened state will be the very wall which will prevent its realisation.

Altered States of Consciousness – A Trance-lation

Altered States of Consciousness are everywhere, and they’re always changing. We enter altered states of consciousness frequently and fluidly throughout each day, and night when we sleep, every day and every night.

Most of us are aware of, or have heard mention, the different brainwaves, measured in Hertz, from Delta to Gamma which range in frequency from <.5Hz up to 42Hz (interesting side note: the national grid operates at a frequency of 50Hz). The human brain at rest is operating in the Alpha Wave frequency, permitting a slow and steady flow of thoughts around 8 to 12 Hz. Our more common brainwave state is Beta Wave, within a frequency of 12 to 38 Hz. Needless to say, there are divisions within the range of this state as we spend most of our time occupying this range. This is where we perform most of our cognitive tasks and are most aware of the world around us. This high frequency range allows for a heightened brain function, as well as excitement and anxiety, and is responsible for making grey matter such a power hungry organ.

When we meditate, we are directly engaged in lowering our brainwave frequency, hence ‘altered states of consciousness’. As we enter these altered states, where brainwave frequency moves from Alpha, a state of calmness, presence, integration of mind and body, to Theta, the threshold state which is where hypnagogic experiences occur, to Delta, which is present during deep dreamless sleep and the deepest levels of meditation such as Buddhist monks might experience after years of dedicated practice.

Our states of consciousness can be varied in many different ways and, aside from deliberate manipulation, we are shifting through a spectrum of frequencies throughout the day. Methods to induce altered states include pharmacological (the use of drugs), spontaneously (daydreaming), physiological (fasting and sex, for example), pathological (epilepsy, infection, psychosis, etc.) and psychological. This last identification is where we might most readily ascribe meditation as a technique of altering consciousness.

Whilst any of the techniques for altering consciousness are effective, there are obvious constraints and side-effects which make many of them undesirable as a means of achieving such a state. For example, certain psychotropics are known to induce certain states of consciousness. However, the results can often be unpredictable, uncontrolled and have associated health risks. Whilst psychoactive drugs may be a most immediate method of bringing tangible and verifiable results in changes to brain function, brainwave frequency and experience, the variables outweigh the real uses for a consistent and sustained spiritual practice. Meditation may bring more subtle results, the sustained practice yields profound and important developments in awareness and our relationship with our states of consciousness throughout alternating frequencies. Indeed, this development of a relationship between our brainwave states and our awareness thereof introduces new avenues to explore our consciousness itself. Indeed, the very task of meditation is to focus the mind upon the mind and subject and object become one – whereby the object of meditation and the subject who meditates are united in stillness.

Resources – OK, so what do I need to do?

In the past, a handful of people have, somewhat coyly, approached me with the delicate subject of meditation and asked if there is a particular practice, book or video. In all cases, there is one particular book which I have found singularly the most helpful. It was the first book upon meditation that I owned and read, and it is still the one to which I refer people. Teach Yourself To Meditate by Eric Harrison has a dreadful and off-putting title, but approaches the subject in an erudite and succinct manner. It is not a particularly long read, which is apt as meditation is something you do not something you read. In the book, Harrison discusses the benefits of meditation, introductory techniques, some methods you can use throughout the day, and methods for more proficient meditators. Importantly, Harrison teaches from a non-religious place.

It is inevitable that, when you enter into the subject, Eastern teachings tend to creep in. As the most reliable and dedicated texts and teachings upon meditation come from Asia, it seems rather churlish to ignore them. Indeed, the first part of Aleister Crowley’s magnum opus, Magick Liber ABA, discusses the work of yoga, including asana, pranayama and pratyahara to an approach to mysticism.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a term that has gained in popularity over the years and has entered common parlance. Indeed, it has been used ad nauseam to the extent where adult colouring books are readily available on every high street under the banner ‘mindfulness’. This is a practice that has been incorporated into many different mystical and magical traditions over the years in one way or another. It is impossible, really, to consider a system of magic that has not held, as part of its oral teachings, some way of conveying the importance of maintaining a mental clarity and focus which, in turn, develops the ritual capability required of a successful magician. Whilst discussing similar topics, an initiate of Maxine Sanders said in passing that she was instructed by Maxine to focus on making the tea, being aware only of each aspect of the process. Making the whole a ritual, she was astonished at her tutor’s ability to discern when the pupil’s mind wandered and chastised her with the command, ‘focus’!

The popularity that mindfulness has gained has evidently come from the acceptance, and adaptation, of Buddhism to the West in the last century. The Buddhist practice of mindfulness is nowhere better exemplified than in the work of Thich Nhat Hahn, a Vietnamese Zen Buddhist. In his 1975 work, The Miracle of Mindfulness, the reader is introduced to the fundamental concepts and practice that enable the meditator to incorporate mindfulness into their daily lives, whilst observing awareness and the changing nature of self, and the natural environment.

Another of my favourite writers on meditation from the Buddhist worldview is Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, who himself teaches through his own experiences as a reluctant and poor meditator. Using his own memories as a struggling meditator, Mingyur Rinpoche is able to direct his teachings to the western mind which finds some of the more esoteric language and methods difficult. In one video, Mingyur Rinpoche delivers the most simple and beautiful techniques of mindfulness, providing us with a meditation technique which we can take with us throughout our day and from which we can establish a regular practice.

Practice

Sometimes, we can run the risk of over complicating what is essentially, and necessarily, a simple thing. Meditation is one such subject which we are all guilty of overthinking and which could not be simpler. There are myriad books, writers and techniques out there, but they boil down to a fundamental practice which can be utilised by anybody.

I am no authority on meditation and am still a beginner, with twenty something years practicing. Sometimes, I have meditated morning, noon and night. At other times, I have gone days, or weeks, without meditating. We are human beings and we are fallible, none of us are perfect. Fortunately, meditation is something we can pick up again and continue wherever we left off.

Whenever someone has asked me if I could give them some technique or practice, I always encourage the same thing: take the time to sit and watch your breath. Nothing could be simpler. That being said, a very wise person once said to me that the ability to achieve stillness meditation in a mountain cave retreat in a Buddhist monastery is fine in itself. But the person who can calm the mind and meditate on a busy tube or subway train at peak rush hour has truly achieved a level of mastery. Therefore, our practice should be relevant to our path and lives. Almost all instructions suggest that it is better to sit at the same time, and in the same place, every time you meditate. This is excellent for building a practice, introducing your mind to a challenging and revelatory system of self exploration. However, I do feel that variety is the spice of life and by introducing some novelty to our experiences, we may hone our skill and develop meditation as a muscle. If we use ritual, we can better apply these foundations in our work. Necessity is the mother of invention and, like the wise lesson above, we can build a meditation practice into our lives in creative and valuable ways.

After all, mindfulness whilst walking, washing the dishes, or making a pot of tea, are excellent ways to develop our ritual skills.