Guy of Warwick features in medieval romance and legend as a questing knight fighting dragons and rescuing fair damsels – which may have led to his legend being confused with the West Midlands slant on St George. But where does the Green Man fit in?

First published in White Dragon, no. 57, Lughnasa 2008

Dragon slaying, rescuing princesses, two of Britain’s most legendary heroes in the mediaeval romance genre have faded in the memory of modern times. How they overlap and relate to a common theme may still be possible to discern through the cobwebs of time. This essay takes a whimsical look at the local legends and possible connections with a land based energy, perhaps the Green Man himself. The local links with names that history once regarded as great include Guy of Warwick, and the most recent patron Saint of England, George. Were these names attached to local tutelary spirits who once resided deep in Shakespeare’s county, Warwickshire?

How did the familiar national figurehead of St George, patronised towards the end of the 14th Century, become embroiled in local English folk legend from his Eastern origins? One of the earliest sources of information about St George is the Golden Legend [1] (circa 1275 CE) in which George is born in Cappadocia, Asia Minor (now in modern Turkey). However, by the 16th Century, another popular text states:

The ancient city of Coventry gave birth to the first Christian hero of England and the first who ever sought adventures in a foreign land; whose name is… St George of England. [2]

The writer has not been able to find a satisfactory source as to what prompted the introduction of this foreign soldier saint into English folk custom. Perhaps he was grafted onto older mythological stock in the knowledge that the story would take due to the popularity such tales had, historically, received. The question remains, by whom? Richard Johnson’s Famous Historie of the seven Champions of Christendom (1596) would purport to be the earliest record which references St George as originating from English soil.

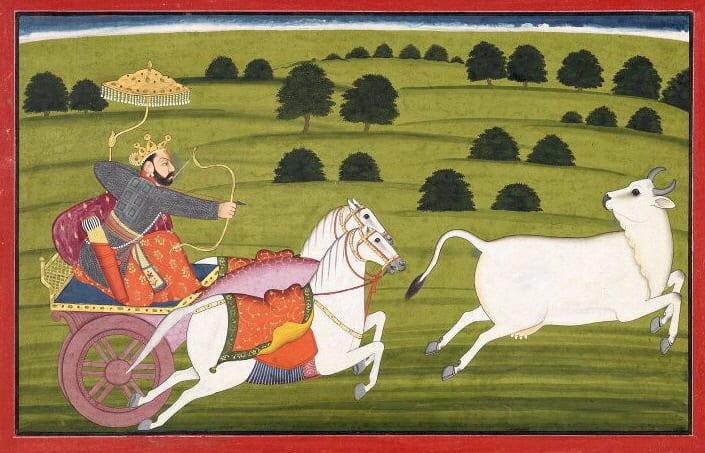

In the legend of Guy of Warwick that we are familiar with, brave Sir Guy endeavours to persuade the Earl of Warwick’s daughter that he, a lot born man, is an appropriate suitor for her hand. in the more common versions, he performs deeds in order to actually convince her, rather than her father (which is customary in such mythologies), that he is a candidate for her betrothal. He variously gallivants and, in the exaggerated tales we have received over time, travels Europe, enters several major battles, and kills a few giants, dragons before returning home to Warwickshire.

After all his impressive actions, he is still deemed unsuitable and the question of marriage inappropriate while a large and savage cow ravishes the countryside of the county. Guy dutifully faces off with the Dun Cow, slays it, restoring peace, and weds the Earl’s daughter.

Unusually in this type of tale, Guy then rejects all of his past glories and retired to live as a hermit in a cave, now on property occupied by the remains of a large house and chapel owned by the Freemasons. When his wife learns of Guy’s death, she locates the cave and throws herself to her death from the overlooking cliff – an area now called Guys Cliffe and a pure invention by the late Medieval and early Modern Earl’s of Warwick to legitimise heritage inherited from a folk hero.

What does this story tell us and how is it related to St George? What of these folk tales, loved of the common man and noble alike, often paraded as mummer’s plays, festivals and revelries at key times of the year? What did they convey to the populace that has been forgotten or misplaced? Why does Warwickshire require two folk heroes of such renown, or may we speculate a connection in mythology that has become separated by time? This might be taken one step further and reveal a Green Man, or vegetation spirit, within these comparable tales.

Relating to the Characters

The first obvious relationship between Guy and George is that they are both historic and important legendary dragon slayers, represented in tales, poems, genealogies and Chop Books of the past. More interestingly, Guy later becomes one of the legendary St George of Coventry’s three sone, who later inherits the Earldom of Warwick [3]. Indeed, in a later rendering of The Seven Champions of Christendom, a mediaeval romance about the more prominent saints and their acts of gallantry, in 1616 CE, St George kills a second dragon on Dunsmore Heath, the reputed site of Guy’s slain Dun Cow. Seemingly, the two myths became conflated in symbolism and relevance, united through a local landscape apparently infested with monstrous beasts.

What’s in a name?

When we look at themes of our two protagonists, we find that, commonly, George originates from the Classical Greek georgios, the meaning of which may be broken down to signify ‘earth worker’ from the element ge, meaning earth, soil, and ergon, to work. From this, we might draw a conclusion that the name started life as a descriptive, possibly denoting an agricultural labourer or farmer.

The 13th Century text, The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints (1275 CE) has this to say on the etymology of the name George:

George is said of geos, which is as much to say as earth, and orge that is tilling. So George is to say as tilling the earth, that is his flesh. And S. Austin sith, in libro de Trinitate that, good earth, is in the height of the mountains, in the temperance of the valleys, and in the plain of the fields. The first is good for herbs being green, the second to vines, and the third to wheat and corn. Thus the blessed George was high in despising low things, and therefore he had verdure in himself, he as attemperate by discretion, and therefore he had wine of gladness, and within he was plane of humility, and thereby put he forth wheat of good works. [4]

All this talk of wine and corn sounds terribly familiar. Interestingly, the above quote states that George has “…verdure in himself…” and closer inspection reveals a dual meaning of freshness and greenness, allegorically that of plants and vegetation.

When we look at the name of Guy, it is a little more complex due to having arrived to England’s shores with the Norman nobility. It would appear to be the Norman French short form of a Germanic original that starts with the element widu, which in Old English denotes ‘wood’. Guy can also stem from the Old French gui, as an occupation name denoting a ‘guide’. It was more popular among the Normans from the former being borrowed from Germanic roots. Interesting to note here that much of Warwickshire at the time was covered by the dense forest of Arden. Further, it is also curious to observe the significance between Guy and the Green Man as representative of the woods and former folk traditions which venerated deities and spirits in the form of trees. As the etymology of George may direct us to a farmer, as worker of the earth, and Guy suggests possible connections with trees and woodland, perhaps there is more going on than meets the eye.

George

In looking at the figure of George, we have elected to pay particular attention to the rendition promulgated by Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765 CE). Worked from an older manuscript which Percy rescued from a colleague’s maid who was using its pages to light the fire. This later retelling of the story provides a more modern, popular version, but also holds some interesting references and ideas in relation to the folkish English George that we shall try to extract.

Surprisingly, from the outset, unborn George is the cause of much strife for his parents and, indeed, his birth is fatal for his mother. We find, at the start, that George’s father Lord Albert resides in Coventry and is High Steward of this Noble Realm [5]. It is worth noting here that Guy of Warwick’s father is also a Steward but to the Earl of Warwick. George’s mother is given as a virtuous and beautiful lady who as a dreadful dream:

She dreamt a dragon fierce and fell,

Conceiv’d within her womb;

Whose mortal fangs her body rent

Ere he to life could come [6]

Here, we might be surprised to note that the hero is first conceived as being a dragon within the womb. Nor is this the first time we see George compared with, or symbolised as, a dragon himself.

Knowing that his wife has had this terrible dream, Lord Albert seeks some unusual counsel. He bids his wife farewell and sets off to find the ‘weird lady of the woods’. Frequently, we are given the impression of a witch living in the woodland and, in part, this would be correct. The word ‘weird’ is highly suggestive and it is perhaps significant that Albert attempts to penetrate the abode of the Lady of the Woods three times before he is successful [7].

The modern word ‘weird’ derives from the pagan past, coming from Old English wyrd, referring to, in its simplest sense, Fate. The concept of wyrd is a little more complex than our common usage, however, and is a subject within itself. together with its meaning and relevance to our ancestors [8]. In its Old English form, wyrd can be condensed to derive from the Latin root wert, meaning ‘to turn’ and, in a more sophisticated understanding, ‘turning into’ or ‘becoming’.

An Encounter with Fate

As a concept, wyrd is the ceaseless flow and ebb of life, the changing tides of time and space. Our predecessors would imagine a great weave in which all things are interrelated in a complex tapestry. Mythologically, this is the product of he Norns who preside over the warp and weft, cognate with the Greek moirai or Fates.

Among the things that Albert encounters at the ‘weird lady of the woods’ realm are dismal yews, associated with death and are commonplace in British church graveyards. Belledonna or Deadly Nightshade also grows at the Lady’s domain, a psychotropic often associated with witches and poisoners. This plant can be seen in famous flying ointment receipts and, of course, modern chemistry has identified the poisonous element as being atropine. This is an hallucinogenic substance that takes its name from atropos, the Greek moirai, one of the three Wyrd Sisters in Greek mythology, who is metaphor for the inflexible finality of death.

Finally, Albert discovers the “…inchanted cave…”, symbolic of the chthonic realm of the sibyl and the earth’s womb/tomb, within which the ‘weird lady of the woods’ resides. The conclusion of the encounter comes when the lady confirms the oracular vision of the dream and announces that Albert’s wife carries a sone like “…a dragon bright…” and that she must die before it is born.

This episode in the story is rife with symbolism, indicating that the ‘weird lady of the woods’ is a weaver of wyrd, a sibyl, soothsayer and witch. It is also worth remembering that her domain, the cave beneath the cliff, is reminiscent of Guy’s Cliffe. In addition, it is not uncommon for fairies to dwell within the hollow hills through which many mortals are said to have passed and dined with the Queen of Elfame, dame Venus. Additionally, there are comparisons here with caves of admission to the Underworld, or realms of the dead in search of wisdom – as our found in Naples, Italy.

When Albert returns home, he finds that his wife has been dead for three days and George has three nursemaids. Here, once again, we see the repetition of triplicities which is significant in traditional British folklore and legend. Indeed, it wouldn’t be a stretch to see in the nursemaids the Norns once again, the ‘weird lady of the woods’ in her triple form. Furthermore, it subsequently transpires that the baby George is stolen by the ‘weird lady’ while the nursemaids were in a mysterious, magical summer. I think it is safe to say, the recognisable symbols of Fate have fingerprints across this entire section of the story. The stealing of the hero child is also analogous to several legends and romances of this type, including Mallory’s le morte d’Arthur, and it is likely assumed that the audience would recognise and understand the motif.

Here, George is then raised in the woods by the ‘weird lady of the woods’ and trained in “feats of arms, and every martial play…”. The comparison with legendary Arthur, who similarly symbolises a dragon (pen-dragon), is taken by the magician Merlin who trains the future King. In the mediaeval romance genre, this theme is indicative of a hero type [9].

Several early symbols mentioned about the actual babe of George should now be mentioned. The first is his reference to being “…fair as the sweetest flower in spring…”. We can see here the beginning of an obvious relationship with the spring season and, consequently, his feast day in April. This poetic device informs, using the language of symbolism, that George is at the earliest part of his journey or cycle. Furthermore, George is noted as having three wondrous marks upon him: A dragon emblazoned on his breast, a blood-red cross upon his arm, and a garter of gold around his leg.

Looking at the garter first, most easily associated with the Order of the Garter, formed in 1348 CE by King Edward III. Queen Elizabeth II is currently the sovereign of the Order and Prince Charles is a senior member. It is believed that Edward III was the first to appoint George as a patron of England, supplanting its earlier Saxon saints, with the incumbent symbols of his newly formed Order. The Tudor period saw an increase in the popularity of Georgian myth and folklore, perhaps as the Tudors were fond of mythologising as a way to establish national identity and legitimise sovereignty.

However, the occult has also laid claim to the garter, Ranging from the Freemasons to Rosicrucians and modern Wicca. The origins of the garter in romance takes us, once again, to King Arthur – this the in the mediaeval romance Gawain and the Green Knight. This anonymously written poem is a tale which references the Green Man and purports to be concerned with themes of annual cycles, self-sacrifice and chivalric virtue. The symbolism of the garter can readily be coupled with the deflowering of a maid and, in this sense, is associated with early spring festivals in the folk calendar where the May Queen, as virginal aspect of the land, becomes fertile and brings forth the harvest in the coming months. In Gawain, we see the hero tempted three times by the wife of his host and he accepts, as a gift, the garter that will subsequently protect his life and reveal his weakness in this morality tale.

The image of the Red Cross upon George’s arm can be explained as the emblem adopted for England’s ensign, associating him with the land [10]. In addition, we see George himself confirmed as the dragon by the image upon his breast. There is no mistaking, at this point, that George is synonymous with the dragon.

In understanding this, we must look at the Arthur as Pendragon. The etymology of Pendragon renders it of a part Welsh and Latin origin. The suffix pen, we are told, denotes ‘head’, while draco is the Latin form of ‘dragon’. It is conventional to understand the title to signify a chief warlord and the symbol fo the dragon is still used as the emblem of Wales. In addition, the draco is a late Roman military standard and, given the mix of sources for the Arthur legends, it is not inconceivable that the dragon theme in the context of the hero indicates a character of martial leadership. Like Arthur, George is a soldier and a leader, so the motif is familiar.

In the language of symbolism, the dragon can also be taken to represent the earth, the ophidian current, taken from the likeness of the snake or wyrm whose holds the earth to its breast. When taken in this context, and given the meaning of the name George as ‘earth worker’, perhaps we can interpret the image of slaying the dragon as representative of the farmer ploughing the earth. Since the earliest myths of dragon-slaying, the dragon or serpent has been synonymous with primal forces, the unmanifest, the untamed and undifferentiated chaos and untamed nature . In the West, the dragon is chthonic, guardians of treasures and wisdom, autochthonous ‘masters of the ground’. In overcoming the dragon, the hero brings order, both in terms of manifesting rites and culture and carving out a place in the land. Additionally, the boon of knowledge is attained, the knowledge of chaos, untamed nature, and the mastery therein. This mastery is the ability to work with the chthonic energies of the dragon, within cultural body enabling sustenance and ‘law’.

Green Man

The association with George and the Green Man begins with a name: Green George. In Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, we hear of a festival rite carried out in Carinthia on the 23rd April, St George’s Day, and among several Eastern European nations a similar ritual is enacted as the principal spring celebration:

… the young people deck with flowers and garlands a tree which has been felled on the eve of the festival. The tree is then carried in procession, accompanied with music and joyful acclamations, the chief figure in the procession being Green George, a young fellow clad head to foot in green birch branches.

There is a song that Frazer describes as accompanying a ritual in some places whereby:

Green George we bring,

Green George we accompany,

He feeds our herds well,

If not, to the water with him [10]

The culmination of these festivals usually conclude with Green George going in the river as a warning to the spirit that the people will follow through with the poorly concealed threat.

In one mention of fertility rites celebrated upon St George’s Day, in the Ukraine Frazer describes how a priest blesses the village crops that are beginning to show green, after which young married couples lie on the ground and roll over the crops in the belief that “…This will promote growth of the crops” [11].

In conclusion, we can see a similarity in both symbolism and character of the Green Man in Spring and the essence of fertility that was attributed to the folk spirit of St George. In a broader mythical sense, we can see that St George is representative of the cycle of the seasons. It is significant that so much of his birth is given up to the ‘weird lady of the woods’, who raises him after his mother’s death. In this sense, he is twice born like Dionysus.

Guy of Warwick

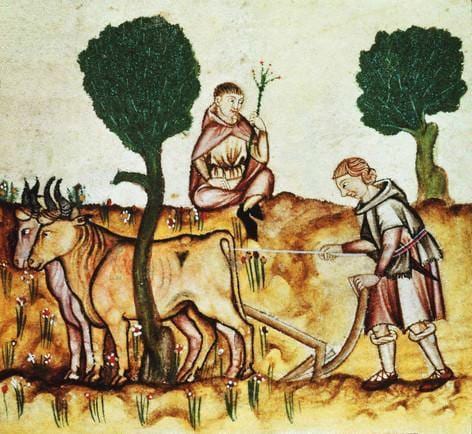

In Guy, it is true that we have another dragon slayer, but it is more proper to look at his mythical beast: the cow. The cow, or bull, has long had a place among religions as an archaic symbol for the natural forces from which life and order emerge, the Great Mother, and the productive powers of the earth. As a chthonic energy, the cow is contested by the bull of heaven, while both give the cron of lunar horns. In similar fashion, the giant dun cow of Guy’s myth provides inexhaustible milk and is clearly emblematic of the Great Mother.

In Norse mythology, that which first appeared in ginnungicap, the pregnant void, as Auðumbla, the divine or primeval cow from which four streams of milk flowed to sustain all that came after. In many ancient verses, we see references to offerings of milk and honey and, given the sustenance these provide, we can perhaps understand the reverence which the cow was afforded in terms of worship and taboo. Indeed, in some tribal cultures, the cow is valued so highly that its milk and blood is used to sustain the people and the animal itself is recognised as currency, itself only providing meat in times of extreme hardship. Indeed, humans are the only mammal to have evolved the specialism to digest milk into adulthood, demonstrating our long history with our bovine companions.

In the story of Guy of Warwick, our hero intends to marry the Earl of Warwick’s daughter, Phyllis, whose name originates in Classical Greek and meaning ‘foliage’. Already, then, we can see a verdant and earthly aspect of the myth in the hero striving to wed his counterpart, the green maiden. After being refused her hand on several occasions, like his predecessors in mythic hero deeds, the father of the betrothed sets a seemingly impossible task – to slay the dun cow.

Within the legend, the dun cow is a giant beast which freely gives of its milk to all the people [12] in stark imitation of ancient and ubiquitous life-sustaining aspects of the Great Mother, Hathor. However, the people, in characteristic greed, milked her dry and the cow became malevolent. In this, we can see the shift from bountiful harvest to barren winter. Equally, the perilous consequences of taking more than is needed are emphasised as the cow is synonymous with sovereignty and the earth.

In the instance of the cow not bringing forth milk, we can see the circumstances in which the chthonic cycle shifts in tide and the hero’s task is to tame nature and become wedded to the sovereignty of the land: becoming the sacrificial husband king of the Earth Mother in much the same way as Arthur. Both Arthur and Guy are representative of the fertility of the land, wedded, while Arthur must retrieve the Grail and restore the Wasteland. Guy, on the other hand, must bring the wild and untamed force to order so that the people might be once more sustained in health and spirit. This, he achieves and he wins the hand of Phyllis, the maid of thriving leaf and bloom.

There is, perhaps, a message within this story that we would do well to heed, as the cow that is Mother Earth has run dry through greed and selfishness, bringing great harm to everybody. A warning, perhaps, against the very situation we find ourselves in today…

In the story of Guy of Warwick, we see comparable themes with that of George, but this myth brings the whole full cycle and to a neat conclusion. Towards the end of Guy’s adventures, he retires to his cave at the foot of a cliff, mirroring in reverse the commencement of George’s story in an enchanted cave of the ‘weird lady of the woods’. Again, we can see the womb of the mother earth and the descent into the underworld, from whom we all proceed and unto whom we shall all return. As with Arthur on his voyage to the Isle of Avalon, Guy returns to the cave to end his days, the symbolic journey to the Otherworld to await rebirth. In folk custom, the sacred king awaits in a cave until a time comes when he is needed once more.

Upon hearing the news of her husband’s fate, Phyllis locates the cave and also descends, like a leaf in autumn, to the world below, to the maw of the opening to the hollow of the earth. We must assume, in the cycle of the seasons, this indicates the return of winter when the foliage that has bedecked the land is fallen and decays upon the woodland floor. Remember here the names Guy (wood) and Phyllis (foliage).

Does the legend of Guy take up where that of George leaves off, blending two branches of noble stock onto the same, common, and much older root which survived in the mind’s of a local folklore? As a central figure to the custom of the Godiva parades which once were celebrated in the entire county of Warwickshire, and now feature only in the city of Coventry, St George is the usual male companion of the naked maid upon the horse and is sometimes depicted in black [13]. However, a modern source links Guy of Warwick to George through Godiva by coupling the Lady with wells in the city that may once have been held sacred:

Guy of Warwick, slayer of dragons and giants, was also associated with Coventry where a large bone, said to have come from a gigantic boar killed by him at Swanswell (Swineswell), was long preserved in St George’s Chapel at Gosford Gate. [14]

(Curious that the boar is also a fertility and harvest symbol to the ancient English…)

Furthermore, we are told that Guy and George could be associated with a cult of Godiva, citing Robert Graves, through a “… possible Arabic cult that reached England via France and Spain at the time of the crusades or a little later” [15].

In A History of the County of Warwick, a similar statement is made, this time with regards to George and Guy:

The Arabic cult may well have influenced the 13th Century romances of St George and Guy of Warwick, in which Saracens and Moors as well as giants and dragons feature prominently. The local tradition of a death and fertility cult would have attracted stories and embellishment from later, more remote sources. [16]

In conclusion, I represent here some interesting, if somewhat speculators, insights into how the myths of these two national and localised heroes may have cross-pollinated or inspired each other, possibly even revealing an underlying theme of the Green Man, most notably obvious in other mediaeval romances of Green Knights (in particular Arthurian lore). The link here made between the serpent, representative of chthonic illumination, and the ‘dragon bright’ that is St George is readily observed.

References

- The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, 1275, Vol. 3.

- The Famous Historie of the Seven Champions of Christendom, Richard Johnson, 1596, p13

- ibid. p264

- The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, 1275, Vol. 3.

- Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, Thomas Percy Vol 3. 1765

- ibid.

- The number 3 features heavily in mediaeval romance prose.

- Wisdom of the Wyrd, Brian Bates, 1996.

- The Famous Historie of the Seven Champions of Christendom, Richard Johnson, 1596, p13

- The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer, 1890

- ibid.

- Folklore of Warwickshire, Roy Palmer, 1976

- A History of the County of Warwickshire: Volume 8: The City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick, 1969, pp 242-247

- ibid.

- ibid.

- ibid.