At least three influential Buddhists and Zen masters are reported to have said that they never trust anyone. The three are D.T. Suzuki, Chögyam Trungpa, and Dainin Katagiri. A 15th c. manuscript at the Vatican also states that ‘trust is the mother of all misfortune’. We’re with the wise folks here.

What’s going on?

In their cultural constitution, our relational selves are based on trust, and it goes to show that without trust, there’s no transaction.

Our cultures and societies are built around our capability to give and receive trust. Those who fail are called traitors.

At a functional level, this is very simple and very clear: Either you are reliable or you are not.

But how clear is this reliability, when we want to talk about truth and its realization, which is something different than talking about relative and absolute states, or mundane and sacred manifestations?

That Zen masters don’t trust anyone may come as a surprize to people living in a world where ‘trust’ is a highly valued commodity – you go to a Zen center or seek a spiritual master because you trust the teaching – but the truth is that in light of the impermanence of all things, trust as a fixed, stable, and reliable entity becomes nothing but another subject to be suspicious of.

As with everything else, the question to ask is about what makes a situation trustworthy, what makes a relationship reliable, and what makes acting according to the situation appropriate.

So it’s not trust that comes first, but rather responding to situations that have trust as a concept in a fluid and transactional mode.

If you think just a little bit about the obvious here, ask yourself: Just how much point is there in trusting people, when people change all the time?

What does it mean, also, to ask that others trust us?

When we ask for trust, aren’t we actually obligating others to rise to our expectation of reliability?

We value consistency in actions that follow the speech-acts, but when we do that, is it really trustworthiness as a stable thing that we value, or more the expectation that, ‘if I do you the favour of trusting you, you also do the same for me?’

And when others don’t rise to our expectations of consistent behaviour, then what?

Zen centers are populated with enthusiastic students who trust masters who don’t trust them. Not all are aware of this, to begin with. Students are devoted in their love to the masters, while the masters keep a hard line that’s called: ‘I’m not impressed.’ Some get the point of that, others take it personally. When the latter happens, it’s easy to see how the initial trust turns into resentment anchored in stories of denigration: ‘Another Zen master implicated in a sex scandal,’ as if a Zen master’s sex life is ever anybody’s business.

That last remark aside, as it requires a different a context to unfold than the cartomantic one, what we can observe here that’s interesting is the intentional asymmetry in the student/master relationship – which has a long history, by the way.

Underlying this asymmetry is an inherent wisdom behind the scene of trustworthiness, where the master simply suggests that if you can act it, you can be it, be that devotion, love, reliability, trust. Being enthusiastic is a mode that activates your emotional field; acting according to the situation, when you show diligence and simply just work towards better self-scrutiny is another story.

Meanwhile, you simply don’t say to others: ‘I trust you.’ I’ve always found this claim completely inappropriate, as it’s devoid of correct functionality in relation to identifying properly the context of the other’s situation. What does, ‘I trust you’, presuppose? That I know you?; that I know your situation? What do we actually know of others? Nothing.

Also, do you don’t go around asking people when you want to divulge secrets: ‘Can I trust you?’, as this is an equally inappropriate way of putting it when dealing with sensitive information.

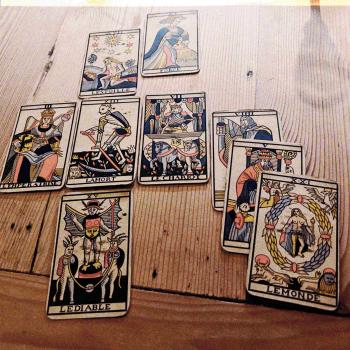

The reason why trust in such situations comes across as awkward is because it lacks illumination, which is what brings me to the card of the Sun in the Tarot.

Graphically and at the level of the image, everyone can see that two people share their mutual trust. But how many think of the underlying structure to this symmetrical relationship: ‘I give you my love, and you give me yours?’

The Sun makes things clear, and it can also burn like a laser through muddled agendas. So here’s what I think of the two people in the Sun card: They invite us to inhabit the space where we can maintain double vision, that is to say, when we can maintain seeing the other from a double perspective.

The subtle question that we can ask ourselves here, as inspired by the idea of the double vision, is the following:

How can I be flexible in my certainty about another? The inverse can also apply: How can I be flexible in my uncertainty about another?

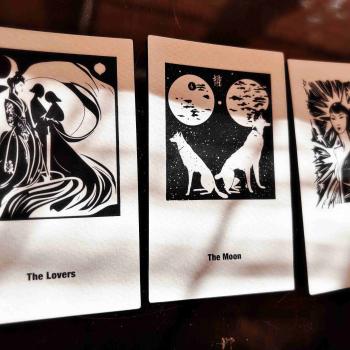

It serves us well to think that when gazing at the moon and minding our own business is not available to us, as far as having to act towards others is concerned, we can think of how to maintain double vision; after all, we have two eyes, suggesting that it’s best not to gaze for too long in just one direction.

In the Sun card people see each other, which is why the Sun has traditionally been associated with vision, especially as it pertains to readings and consultations for health situations.

But how flexible are they in this act of seeing, especially since seeing is culturally informed, often acquiring particular shades that’s constitutive of identity?

Why double vision?

One of my favorite literary critics, Gabriel Josipovici, has this to say in his brilliant book, On Trust, where he makes a very apt comment on what happens when, in our desire to experience the fullness of love, or its continuos expression, we forget to think of it in terms of its finitude once death occurs. He calls this situation “the double vision” of the sense of life’s abundance that entails the event of death, also as an abundance.

“[The] denial of the dual vision… in the end entails a denial of the world we live in and, ultimately, of ourselves as embodied beings existing within that world. Yet such is the nature of suspicion that, once unleashed, it appears to produce a totally convincing and self-consistent world, not simply an alternative way of looking at things but the only way there can possibly be.”

Zen masters are masters because of their suspicion and their ability to maintain double vision in doubting everything they know. When they say, ‘I trust no one’, you can stake your life on it that what they’re doing is demonstrate correct function in accordance with identifying properly what the situation always IS. If you doubt this, ask your cards:

How can I love without trusting anyone?

Perhaps they’ll say something of this sort:

You think you know what the other wants. Think again, and then consider your commitments. What function do they have? ‘Keep going’ is the same as acknowledging movement, and that includes the movement of your consecrations. You can love without trust if your moving is seemly.

♠

Stay in the loop. Read like the Devil. The next cartomancy course, Radiant Reading opens for registration on April 19. Hop on board for a run of advanced Marseille.