This is the second in my series of posts “Getting Theological.” The first, on God, was in direct response to Tony Jones’ challenge to progressive theo-bloggers to do more theology in public.

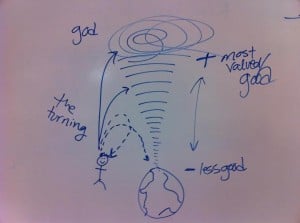

Like my other post, I frame this one with words that help me articulate what I believe it means to be human. The picture here is more Augustine or Plotinus than Luther or me, but gives you a pretty good sense of what the board really looks like when I’m teaching those folks and their ideas.

Like my other post, I frame this one with words that help me articulate what I believe it means to be human. The picture here is more Augustine or Plotinus than Luther or me, but gives you a pretty good sense of what the board really looks like when I’m teaching those folks and their ideas.

On to being human:

Martin Luther

“Now, is he [the Christian] perfectly righteous? No, for he is at the same time both a sinner and a righteous man; a sinner in fact, but a righteous man by the sure imputation and promise of God that He will continue to deliver him from sin.” (LW 25:260)

Some of us Lutherans love our lingo, and when it comes to this idea from our claimed reformer, the Latin he wrote it in must be invoked: To be human is to be simul justus et peccator. Simultaneously saint and sinner. Righteous and flawed. Graced and broken. All at the same time. Never one without the other.

And yet …

When people commit unspeakable atrocities – James Holmes shooting up the movie theater at midnight, Mohammad Atta leading a band of terrorists into airplane cockpits on a sunny Tuesday morning – we want to believe that they are somehow different from us. The governor of Colorado even referred to Holmes as a “creature” on Meet the Press … as if he wasn’t even human. As if that somehow protects us. From ourselves?

But he is. They are. Just as human as you and I. And we are as capable of such evil as they, given circumstance and experience and motivation. Even if we profess belief in God. Even if we believe that we are in the image of God, created by God, and accompanied through life by the divine spirit.

When people accomplish heroic feats – Captain Sullenberger landing a passenger jet on the Hudson, Whitney Houston creating beautiful song with her small powerful body – we lift them up and want to believe that we could be as good and inspiring. We shower attention and praise on those who make us believe we can be better … creating celebrity and superhuman beings in the process. As if that allows us to escape the messy struggle that life is.

But heroes are human too. Whitney’s addictive demons got the better of her in the end. Sully was a well-trained guy doing his job even in a moment of crisis. Neither one of them, nor any other hero or celebrity we valorize is perfect. Perhaps this is why when those people fall off the pedestals we shoved them up onto, we are particularly harsh. Anna Nicole Smith’s life and death was as much tragedy as joke. Pat Tillman’s story was manipulated from beginning to end by a government desperately in need of heroes.

Being human is all of this and is always betwixt and between. When Luther speaks of the person as simultaneously saint and sinner, he reminds us that no one is fully either one all of the time or forever. What is most compelling about this understanding of being human, for me, is that it is a built in corrective. For those who need to hear it, you too are justified by God, created in the image of God, supported by the grace of a God who doesn’t judge you based on your actions, appearance, or social position. And likewise, for those who need to hear it, you are flawed, limited, unable to live up to even your own very best ideals and trapped by systems that privilege you when you did nothing earn it.

And while Luther believed that the human being was little more than a beast standing between two riders, going wherever the rider willed, be it Christ or the devil, I have a bit more confidence in human agency and will. With an affirmation that God is source and sustenance of life (see previous Getting Theological post), I believe this is true but I think there is more that is true: There is a goodness in being human that comes from being grounded in community, tied up in relationships with other people and their flourishing. Commitments to and work for justice in this world is as much dependent on that as it is dependent on a transcendent vision and lure from God for those of us who believe.

Much of my theological anthropology, fancy-talk for how one understands what it means to be human in relationship with God, is framed by this sixteenth century reformer (without the gender exclusive language). He also talks about the four types of relationship that inform our being human. With God. With the world. With other human beings. With oneself. This comprehensive relational understanding of being human works. It calls attention to the multiple directions, various commitments, different callings, and complicated pressures and factors always informing our being human.

It is in these relationships, then, that we are justus et peccator … saint and sinner … graced and broken … righteous and humbled.

Simul.