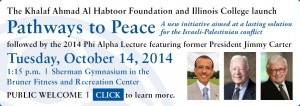

I read former President Jimmy Carter’s latest book this summer in preparation for today. The 90-year-old is speaking on my campus today alongside Khalaf Al Habtoor, a major benefactor of the college, and former U.S. Representative from Jacksonville, Illinois, Paul Findley. A major campus initiative titled Pathways to Peace is being announced, and the college’s archives named after Dr. Al Habtoor and funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities were dedicated yesterday.

I read former President Jimmy Carter’s latest book this summer in preparation for today. The 90-year-old is speaking on my campus today alongside Khalaf Al Habtoor, a major benefactor of the college, and former U.S. Representative from Jacksonville, Illinois, Paul Findley. A major campus initiative titled Pathways to Peace is being announced, and the college’s archives named after Dr. Al Habtoor and funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities were dedicated yesterday.

My colleagues have been busy getting so many things ready. I’ve been watching a lot of out-of-town men and women in serious dark suits comb the campus and the building in which the public event will be held for the past week. I’ve also been checking in with my students to see what they know about Jimmy Carter. The notion that he was president is pretty vague for people who were born over a decade after he left office. The fact that he was a major force behind the growth and expansion of Habitat for Humanity is something that more of them can connect with.

In all of my classes, I plugged the book. A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power came out earlier this year, and talks about topics that I teach and write about nearly every day. In my Religion and Literature class this semester, we’ve read two novels, The Poisonwood Bible and The Color Purple, in conjunction with feminist and womanist scholarship on religion, gender, race, and class. To those students, many of the topics in A Call to Action resonate. In my Women, Race, and Theology class we are about two embark on two weeks focused on feminist and womanist biblical scholarship.

In less academic terms than, say, Phyllis Trible and Patricia Hill Collins, Carter takes on the intersection of the bible and religion with gender inequality around the globe. He weaves in personal reflection with basic scholarship on the history and criticism of biblical texts.

On segregation and divorce, he says:

“I began to realize for the first time that I lived in a community where our Bible lessons were interpreted to accommodate the customs and ethical standards that were most convenient.” (p.9)

Connecting to sexism and misogyny, he notes:

“Not yet seriously questioned or rejected by many secular and religious leaders is a parallel dependence on selected verses of scripture to justify a belief that, even or especially in the eyes of God, women and girls are inferior to their husbands and brothers.” (p.11)

The “call to action” comes early:

“It is crucial that devout believers abandon the premise that their faith mandates sexual discrimination.” (p.18)

And a list of 23 suggested actions concludes the book (p.196-198), including:

“2. Remind political and religious leaders of the abuses and what they can do to alleviate them.”

“9. Apply Title IX protection for women students and evolve laws and procedures in all nations to reduce the plague of sexual abuse on university campuses.”

“18. Encourage more qualified women to seek public office, and support them.”

“19. Recruit influential men to assist in gaining equal rights for women.”

On the last point, it is clear that Jimmy Carter is one of them.

The value in this book is its accessibility to nonscholars and its attention to the manifold ways that the intersection of religion, sexism, and male power has been detrimental to women. Topics like war, prisons, capital punishment, genocide, and child marriage sit alongside maternal health, rape, spouse abuse, and equal pay as issues where a deadly confluence of patriarchy and religious literalism have impacted women around the globe.

If you are reading this on Tuesday morning 10/14/14 and want to watch the livestream of the public event on my campus today (1pm CDT), click here.