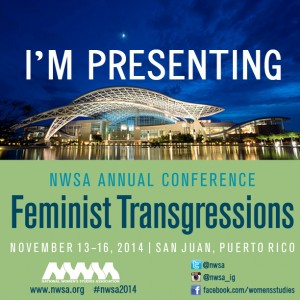

I’ve escaped the cold blast hitting the Midwest this week by heading to the National Women’s Studies Association annual conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

I’ve escaped the cold blast hitting the Midwest this week by heading to the National Women’s Studies Association annual conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Today, I am spending time in a workshop for Program Administrators and Developers, as a former chair and founding member of the Gender & Women’s Studies Program at Illinois College. I’m looking forward to spending time with other colleagues who share the challenges and opportunities of leading and shaping interdisciplinary programs that call for innovative teaching and learning at colleges and universities facing significant market challenges and cultural shifts.

I’ll be speaking on a panel that is specifically considering the NWSA’s Tenure and Promotion Guidelines for Women’s Studies, a statement on Women’s Studies Scholarship newly released by the organization with the goal “to both aid candidates in navigating these barriers while calling for change in institutional practices.” Having served as chair of a GWS Program for about five years, and now serving as chair of the college’s retention and promotion committee, I have some thoughts about the process and how scholars and teachers in women’s studies can talk about our work in ways that both meet and transform institutional and academic-cultural standards.

Specifically, several things that are distinctive about women’s studies as a field emerge in the guidelines. For scholars and educators in women’s studies, some of these things can be and have been impediments to navigating institutional tenure and promotion processes. This includes the fact that women’s studies has always been inter- and multi-disciplinary as a field, often causing tension between faculty navigating competing expectations of departments on campuses. The guidelines also note that women’s studies scholarship has often and taken place in unconventional forms, including new media and via partnership with community leaders. Finding a place within tenure and promotion criteria to value an essay co-authored with the director of the local homeless shelter based on students work in the community, or a hundred published pieces on a nationally read blog, proves to be a challenge at some institutions. Additionally, as the guidelines point out, those of us working in the field are inherently critical of systems of power and often likely to have our work viewed skeptically.

Rather than impediments, though, feminist scholarly and pedagogical strategies are the things that are shown to increase levels of student learning, student engagement, and the all important factor of student retention. This all in fact predated what the national academy now recognize as “high-impact educational practices.” The Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) and its project on Liberal Education and America’s Promise (LEAP) highlights and discusses these things at length, including integrative learning in such models as learning communities, civic and community engagement, global learning and diversity, and collaborative learning. If candidates are able to frame their work in light of this national conversation, and institutions are able to understand the proven value of this work and alter their criteria appropriately, practices and processes can change in significant ways.

As I’d suggest has often been the case, feminists, scholars, and educators in women’s studies have been ahead of the curve on this one. It’s good to see that the national academy has seen the light.