If you’ve been reading the series of posts in which I “get theological,” then you might have noticed that I use and reference the bible sparingly. A commenter on my very first post, on God, noted this immediately, saying that there “isn’t a whole of of scripture or Christ in your brief analysis.” True enough. In part this is because I think that there is plenty to say about God that is beyond the bible. (Cue righteous indignation from certain Christians now.)

If you’ve been reading the series of posts in which I “get theological,” then you might have noticed that I use and reference the bible sparingly. A commenter on my very first post, on God, noted this immediately, saying that there “isn’t a whole of of scripture or Christ in your brief analysis.” True enough. In part this is because I think that there is plenty to say about God that is beyond the bible. (Cue righteous indignation from certain Christians now.)

It will come as no surprise, then, that my understanding of the bible does not include the concept of inerrancy or infallibility. That does not preclude me from having a sense of the bible as the word of God … it just means that I understand it’s authority differently.

First, the bible is a human book. Written by humans, compiled by humans, shaped, ordered, and disputed by humans. So everything I wrote about what it means to be human has an influence on what I believe about the bible. Graced and broken. Gifted and flawed. Sainted and sinning.

Second, God works only and always through human beings, despite their flaws and limitations. So when it comes to communicating truth, how else would it happen? And how great it is, that this is how it happens.

Third, this means that our reading and interpretation of biblical texts, canonical, apocryphal, non-canonical, and those yet undiscovered, is part of an ongoing process of revelation. God didn’t say everything that there was to say to human beings a few thousand years ago, and then stop. As the UCC motto says, “God is still speaking.” Thank goodness.

Because the world today is radically different as well as shockingly similar to the ancient world in which the canonical bible came to be. It is different in that we confront social, political, and scientific realities that ancient authors couldn’t have imagined. It is similar in that human beings have always been able to create amazing and inspirational communities, and always been captive to their own worst instincts and limits.

Do I think the bible is true? I think it communicates some truths, yes.

Do I think that everything we need to know about God and the world is in the bible? Of course not.

And yet it remains a powerful witness to truth, God, the world, and our human community throughout time. It has authority in the same way that tradition has authority. Until it doesn’t.

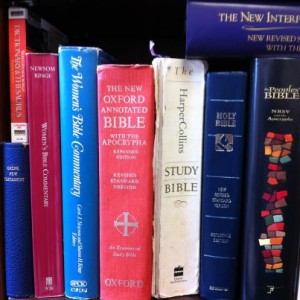

I have a lot of bibles in my possession, each signifying something about this book of books. In my office you’ll find The HarperCollins Study Bible that is the standard for use in my classroom and scholarly work; the Greek New Testament that I can’t read but picked up once I realized the bible had been written in ancient languages; the RSV, NIV, NRSV, and other translations I’ve gathered over the years for comparative and teaching purposes.

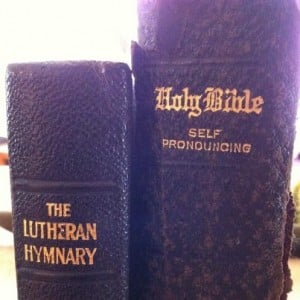

Then at home there is another HCSB for good measure, a Good News Bible that was presented to me by the women of the church as part of our third grade Sunday School rite of passage (now there’s a “translation” not to be missed), and several other sacred texts that have found their way to me after the deaths of grandparents.

Two of those texts, worn from age and use, say something else entirely about the bible. As we first flipped through one small old bible, two small black and white photographs fell out. One is of eight cows and a grove of trees in the distance, with handwriting on the back: Cattle sold April 1952. The other is of a man on a tractor, snow-covered barn, barren trees, and chilly prairie landscape surrounding him, with handwriting on the back: Winter 1952.

The other text is The Lutheran Hymnary with my grandmother’s name embossed on the cover, inscribed to her from her in-laws on her birthday in 1946. Tucked inside it as a page marker perhaps, page 18 from a seed catalog listing soybean varieties and characteristics.

I tell these stories because whatever else I say or know or don’t know about the bible, I know that it has a unique role in many people’s lives. It is personal, beyond just a book. These artifacts of the daily lives of my grandparents, seeds, snow, cows, and tractors, were part of their lives and part of their faith and part of the tradition that I inherited.

So is the bible.

Christian communities have found in it source and sustenance for millennia. It has also been the root of controversy and a weapon of choice. It has cultural and political influence in this country whether you personally accept its truth or not. And like tradition, the bible is something that each member of the Christian community has to reckon and wrestle with. To see how it is graced and how it is flawed. To take better care with how and when and why it is used.

To see it for what it is. And what it isn’t.