In the Beginning, there was a human being who was alone. God had already created the entire material universe and filled it with wonders. Stars had been kindled in the heavens, and worlds spun out around them. Seas had been divided from the skies, and night from day. The sea teemed with fish, and the sky with birds, and animals were all multiplying in the forests of the world. All of this was “good.” Adam being alone was not.

Why this imperfection in the scheme of creation? The first account of Creation does not involve any such complication: God creates one thing after another, and then on the sixth day He creates human beings: “male and female,” and then He looks at the finished work and declares it to be “very good.” Why, then, in the second account of Genesis, are we shown a human being alone?

John Paul II draws attention to the fact that there are a number of events which take place in the spiritual life of man that must be undertaken in solitude. Adam does not simply come into the garden, sit down, munch on a fig, and start feeling sorry for himself because there is no one else there. He has work to do, and he gets down to it more or less immediately.

His first task is to understand what sort of a creature he is. He is a unique creation. In all of the other days described in Genesis, there are vast principles being set in order, entire realms of the earth being filled with life. If you wish to picture what happens on the fifth day, it’s not enough to fill a field with all of the species of the African Serengeti, or to populate a garden with hop-toads and pelicans, reclining bucks and indolent lions. All of the multitudinous varieties of reptiles, the different species of mice, even the extinct dinosaurs, are all made. There are entire species that rise, live, and fall within this space of time, giving rise to others that fill the earth afterward. The scale of it can’t be conceived all at once by a human mind.

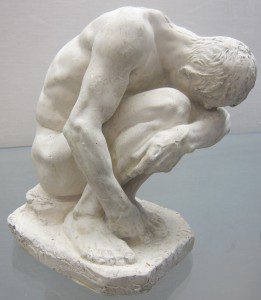

Then comes the creation of man. A little pile of dust is scraped together, a human form is made, and life is breathed into it. Of course, that isn’t literally what happens: God doesn’t make a clay golem and then animate it with His spirit. What actually takes place is that some bit of ordinary matter, lacking self-awareness and divine life, is taken and altered. According to Thomas Aquinas, who is quoting Aristotle, this body is “a little world,” which contains all of the elements of the rest of creation. God makes this little world out of matter, and He infuses it with a kind of life that nothing else in the universe has ever possessed.

For the first time, there is a spiritual being that lives in a material body. That might not sound all that exciting, and over history a lot of people have been nonplussed. From Plato to the New Agers, there have been those who have believed that true human nature is purely spiritual, that we are spirits that somehow got trapped inside of bodies. They see the body as an inconvenient machine, a disobedient robot that is difficult to control. It keeps the elevated spiritual principle from being able to enjoy the clear sight of the realm of the forms, or from wandering through the celestial spheres as a being of pure light. In some cases, such theories give a little more credence to the material nature of human beings: perhaps the body is a sort of egg, or womb, out of which the spirit is eventually going to be born. In any case, the body is ultimately a bit of detritus which will be discarded when the spirit comes to maturity in death.

Christianity has always said the opposite, yet the Platonist hangover has been a long time receding. Theology has tended to concentrate on the intellectual and spiritual. Although the theory that matter itself is depraved was officially denounced as a heresy within the first centuries of Christianity, the prejudice against the body has remained. It has been treated primarily as something fallen, as the “flesh” which must be overcome if we are to achieve salvation.

John Paul II goes back to the Beginning to show what the body is actually for, and how it relates to the human being as a whole. Instead of focusing on how the body might be subjugated to the Will and the Reason, he wants to know why the body is important in the first place. Why, when God turned within Himself and said, “Let us make man in our image and likeness,” did He decide to make a creature that was both body and spirit? Why is it man, and not the angels, who are made in the “image and likeness of God,” and what does that say about the meaning and dignity of our bodies?

Photo credit: Pixabay