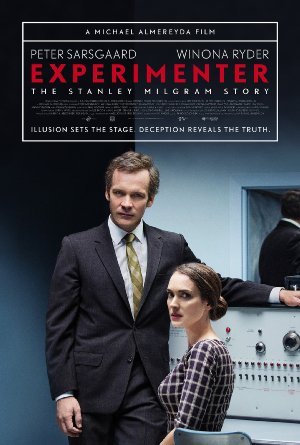

In 1961, a professor at Yale named Stanley Milgram conducted a now-famous series of experiments to test the power of authority in people’s lives. These ‘obedience experiments’ form the core drama of the creative 2015 biopic, Experimenter. The test involved two subjects, who were told they were part of an experiment and given the roles of ‘Teacher’ and ‘Learner.’ The Teacher was given a series of test questions to read to the learner in the next room and if the Learner got a question wrong, the Teacher was to give him an electric shock. The shocks began with a small, but still testy, 25 volts and went all the way up, incrementally, to 450 volts. Milgram wanted to see if anyone would continue to give shocks all the way to the end if told to do so by an authority figure.

Milgram was shocked (pardon the pun) to find that nearly 65% of participants went all the way to 450 volts, despite the Learner’s screams of pain and eventual silence. Of course (and this is not a spoiler), the pain was staged, the Learner was an actor (in the film excellently cast with Jim Gaffigan) who wasn’t actually being shocked. Nonetheless, the subjects playing the teacher role never once tried to open the door to check on the Learner whom they thought was in great distress, maybe even dead. Only 35% out of hundreds of subjects refused to continue administering pain, despite the persistent instruction of the authority figure in the white coat telling them that they must continue for the purposes of the exercise.

What made this experiment so compelling for Stanley Milgram was that he was Jewish, and he did the experiments only 16 years after the end of the Holocaust. This was the same year as Adolph Eichmann’s famous trial in which the Nazi henchman claimed to merely be following orders, saying, “I never did anything great or small without obtaining in advance express instructions from Adolf Hitler or any of my superiors.” In the film, Milgram debriefs some of his test subjects with questions like, “Why did you listen to this man and not the man in pain?” To one man (played by John Leguizamo) he asks, “Who bore the responsibility for the fact that this man was being shocked?” The man’s answer is telling, “I don’t know.”

What Professor Milgram wanted to know was, how is systematic genocide possible in the modern world? How can civilized human beings act so barbaric? And, is the character of the typical American any different from that of the typical German? His answer (at least as the film portrays him) is ultimately that there is both an external reason: we sometimes act against our better nature because the situation demands it, and an internal reason: there is such a thing as an ‘agentic’ personality that simply follows the rules of authority and will not go against the rules even if common sense or morality dictate resistance.

What was interesting to me about the film were Milgram’s colleagues, who not only predicted that he would have a hard time getting anyone to give the full range of shocks, but were offended by his conclusions. One professor even claims it is the job of science to lift up human ethics, not drag it down. Many academics then and now, despite the traumas associated with World War II, still refuse to believe that human nature is inherently evil. Even Milgram believed that his experiments showed more about the ‘plasticity’ of human nature, than any kind of evil side of humanity. But, the Holocaust cannot be explained by human nature being good but bendable. The old Calvinist view of total depravity, that sin has naturally caused every part of human nature to be fallen, seems like the simplest and most likely explanation (to put Ockham’s razor to use) for the Holocaust, especially given the fact that genocide is a regular occurrence, not a one-time anomaly. As an old preacher once told me, “I’m not Hitler or Stalin, but it’s not for lack of talent.”

But, even with a biblical view of human nature, the Holocaust is still not easy to understand, especially when you start putting yourself in the shoes of the German people. Watching this film, you should ask yourself not just, ‘What would I have done in Milgram’s experiment with only a lab technician to disappoint?’ but ‘What would I have done in Nazi Germany if compelled by a gun to the head to join the SS or drive a train car to the gas chambers?’ We know that the number of Christians who actively opposed Hitler in Germany was small. We would all like to think that we would have been like Dietrich Bonhoeffer in speaking out (and apparently getting involved in an assassination attempt), but the reality is that few of us cherish submitting to martyrdom like Bonhoeffer.

Experimenter as a film is very factual and surprising. I was expecting it to play out the initial experiment in a very dramatic way, only revealing the twist of the actor at the very end. But, the film plays more than fair, showing the setup with the actor as we go along. What keeps it from being a documentary is the drama around Stanley and his wife, as well as his career path and response to his work. We also learn that the obedience experiment was not the only experiment Milgram did, he also did a number of other interesting studies: the small world experiment, singing before strangers, the lone skygazer, and the power of photographic evidence among them. You’ll have to watch the film to understand what those studies were about, but the obedience experiment remains Milgram’s most famous study.

Peter Sarsgaard as Milgram breaks the fourth wall to narrate much of the action to us, an effective technique that emulates a scientist interpreting experiment data. Another interesting technique that director Michael Almereyda employs is the use of back screens that are very obviously back screens, as the characters are in color and the screens show black and white footage. This technique evokes 60’s films such as Psycho and helps situate us in a different era, while still helping us identify with the characters, who seem modern, and whose work is still very resonant today and not stuck in some bygone era. A third technique involves characters breaking into song at points, including Milgram himself singing the words of Oscar Hammerstein’s “Some Enchanted Evening”: “Who can explain it? Who can tell you why? Fools give you reasons, wise men never try.” The words in their original context refer to love, but in the film point to the difficulty of explaining human nature through scientific observation.

Perhaps the most jarring technique the film employs is having an elephant- a literal elephant- follow Stanley as he walks. This happens briefly and is not referred to by any of the characters. The obvious reading of the elephant is that he’s the ‘elephant in the room.’ But, what is the elephant? What is not being talked about in a film that explores so much and asks so many good questions? The elephant only appears twice in the film, near the beginning and near the end, but Stanley’s dialogue at those moments is significant. The first time the elephant appears, Stanley is talking about his birth and upbringing and it’s the first time we learn that he is Jewish. The second time it appears, Stanley is talking about 1984, the year he lectured frequently (often about George Orwell and his famous book about authority, 1984) but also the year he died. Birth and death invoke ultimate questions about God, religion, and the afterlife. But, the film never mentions God or the afterlife. In trying to understand the subject of authority, as well as the depths of human nature and depravity, for many people, including researchers who begin with naturalistic presuppositions, God truly is the elephant in the room.