When a colleague and I talked about the work of Joel and Ethan Coen on a recent podcast, we spent a great deal of time discussing how the brothers are Old Testament filmmakers. Themes of impending judgement, an angry god and the folly of man crop up repeatedly in their work, and their protagonists are rarely shown much in the way of mercy.

So imagine my surprise when “Hail, Caesar’s” very first shot was the image of the crucified Christ.

I might be mistaken, but I believe this is the first time the brothers have dipped their toes into New Testament waters. And they dive in, giving us a protagonist who’s a devout Catholic, the production of a studio blockbuster about the crucifixion and what might be the funniest theological argument I’ve seen put to film. Of course, being the Coens, there’s the suggestion that all this belief is for naught, but there are subtle hints of grace amid the cynicism. But if you don’t feel like digging deep, don’t worry. There’s plenty of silliness to enjoy.

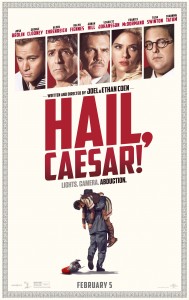

“Hail, Caesar!” follows Hollywood fixer Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin) over one day in 1950s Los Angeles as he puts out a variety of fires to keep Capitol Pictures churning outs hits. Mannix’s day — book-ended by confessional visits to his priest — includes keeping a starlet’s cheesecake photos under wraps, calming a persnickety director, avoiding twin gossip columnists, and helping a pregnant actress adopt her own baby to avoid a scandal. He’s also contemplating an attractive job offer from Lockheed Martin. Oh, and the studio’s biggest star, Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) has just been kidnapped from the set of Capitol’s religious epic, “Hail Caesar — A Tale of the Christ.”

The Coens have a tendency to follow their most introspective works with some of their silliest. “Blood Simple” begat “Raising Arizona,” “Fargo” begat “The Big Lebowski,” and “No Country For Old Men” begat “Burn After Reading.” “Inside Llewyn Davis,” their last film, was a rain-soaked rumination on ambition and missed chances. Following tradition, “Hail, Caesar!” is a bright, broad and often very funny shaggy dog story that allows the Coens to indulge their love for Hollywood’s Golden Age. While there’s a mystery to solve, the filmmakers are more interested in digressing from the main plot to stage an Esther Williams-style water ballet, a lively song-and-dance number, and a date between a singing cowboy and a Hollywood starlet.

Much of this is delightful. The Coens’ precise direction, coupled with Roger Deakins’ gorgeous cinematography, wonderfully mimics the Technicolor vibrancy of Golden Age classics. The hallmarks of a great Coens screenplay are on display: the in-jokes (Capitol Pictures is the same studio Barton Fink wrote for); the ludicrous, rat-a-tat dialogue; even the glorious names the brothers’ love to give their characters (my favorite is Lawrence Laurentz). Coen newbies like Scarlett Johansson, Jonah Hill, Channing Tatum and Ralph Fiennes have a blast with the dialogue; Fiennes’ pronunciation of “rodeo” enters the great tradition of weird pronunciation by Coen characters, on par with John Malkovich saying “memoir” or Steve Buscemi calling it “Los Angle-es.” And their normal troupe is willing to do anything they’re asked, so you get Tilda Swinton showing up as twin gossip columnists, Frances McDormand appearing for one hilarious scene, and Clooney lowering his IQ to play yet another Coen doofus — and doing an uncanny, chuckle-inducing take on Charlton Heston. Stealing the show from all of them, however, is Alden Ehrenreich, who is wonderful as Hobie Doyle, a naive singing cowboy being forced to star in a drawing-room drama. A scene between Ehrenreich and Fiennes centered around the phrase “would that it were so simple” immediately joins the pantheon of funniest Coen scenes.

Much of “Hail, Caesar” moves like a sketch comedy, jumping from one riff on classic Hollywood to another while occasionally checking back in with Baird’s kidnapping at the hands of a Hollywood communists or following Mannix to a business lunch with his suitors at Lockheed. Not everything works. More than usual, you can feel the Coens straining to hold the disparate parts together, and while everyone’s giving it their all, a few scenes still manage to fall flat (Jonah Hill’s glorified cameo lands with a thud). For every moment that doesn’t work there are two that the brothers pull off wonderfully — the “would that it were so simple” scene and an extended tap dance number featuring Tatum come to mind — and somehow they’re able to deliver something distinctly recognizable as their own while avoiding self-parody.

And like most of their films, it’s not as readily disposable as one might think. While silly, the film also gives the Coens the excuse to indulge in an exploration of belief, both political and religious. There are Communist screenwriters who aim to woo Baird away from capitalism (and Capitol Pictures), and it’s no coincidence that it’s a cowboy who ultimately comes to Baird’s rescue. There’s a sequence involving two rabbis, a priest and a minister who convene to discuss the studio’s Christ story that ultimately devolves into a scene of comedic squabbling about the nature of the trinity, depictions of the godhead and the “fakiness” of chariot chases. There are dailies of a religious film with insert shots stating “Divine Image to be shot,” and a speech at the foot of the cross that moves everyone, at least until the actor forgets his lines. Some of the deeper meaning behind these scenes is obvious; others, like the best work of the Coens, will probably drive curious viewers back several times to study.

The peculiarities of faith have long interested the Coens. “Barton Fink” turns into a surreal descent into hell, “A Serious Man” is an exploration of Job, and “O Brother, Where Art Thou” soaks Greek myth in the sights and sounds of Southern Gospel. But while the brothers have often explored religious rules and conduct, it’s always been with an arched eyebrow. As mused upon in this great conversation between critics Matt Zoller Seitz and Jeffrey Overstreet, the Coens are filmmakers who would probably best be described as “spiritual but not religious.” Their work definitely speaks of a higher order to the universe, one that’s usually inscrutable and often ready to judge. But they’ve always cast a wary glance at anyone who thinks they can understand how any of it works or who claims to have definitive answers; stubbornly searching for answers and refusing to accept life’s mysteries is a key theme of their work (it’s actually the entire theme of “A Serious Man.”) And here, it’s no different. People who subscribe to radical political beliefs have their plans thwarted or are revealed to be imbeciles. Religious leaders are quick to bicker about interpretations of the faith and waive off any competing views. An actor can deliver a religious speech that moves people to tears and then, five seconds later, curse like a sailor; the same people making the religious film don’t even know whether the actor playing Christ deserves a hot lunch or boxed one.

In the world of “Hail, Caesar,” Hollywood is the dominant religion. The film has the feel of a passion play (I must admit I wasn’t the only one to realize this; Alissa Wilkinson’s review of the film for Christianity Today looks at it through that lens as well), with Mannix as the suffering savior of Tinseltown. He’s the man whose job is to present Capitol Pictures and its stars as flawless and blameless to the public. He cleans up Hollywood’s sins (indeed, one character even takes on stars’ prison sentences when needed; the LA version of substitutionary atonement ). He’s tempted to stray from his path, wooed away by a suitor promising comfort, wealth and power. He spends a tumultuous night in prayer and makes his final decision at the foot of the cross (on a soundstage). He protects, defends and cleans up Hollywood’s sinners because he says he believes the stories are moving and worthwhile, even if he’s just saying that to keep his stars in line. Of course, we’ve just spent two hours seeing how ludicrous and fake it all is. His belief, like the others, is in something artificial and silly.

But the cynicism is a bit tempered here. For maybe the first time in their career, there’s a suggestion that maybe the Coens are being a little kinder to the faithful . Mannix isn’t portrayed as a dummy; he’s competent, cares about his family and does good work. Brolin plays him as a smart, decent man. He may be keeping Hollywood in line, but he finds his power in his Catholic faith —which, aside from a few gentle chuckles earned in confession, is treated fairly. He goes to confession. prays the rosary and, when struggling with a decision, takes his priest’s counsel, which says “God wants us to do what’s right.” His faith sustains him, and he helps others (this is the first Coen Brothers film in recent memory where everyone gets more or less of a happy ending). Have the brothers softened on faith? Has bringing some New Testament into their work allowed them to bring some grace with them as well? Or is Mannix’s Catholicism — so dependent on ritual, monologues and visual aids — as fake as Baird’s religious movie? Is Mannix’s uncomplicated faith treated with reverence because it’s simple, while those who would overly explain theological minutae and cling to certainty are mocked (at one point, Mannix says “people don’t want facts; they want to believe”) ? Isn’t there one clear point they’re making in the midst of all the silliness?

Oh, would that it were so simple.