Note: Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq” just became available on Amazon Prime this week. I thought it was appropriate to share this piece, which was edited from a blog post I did last year at my previous site.

In Abigail Disney’s 2015 documentary “The Armor of Light,” Rev. Rob Schenck recalls meeting with the father of a young man killed during a mass shooting. The film doesn’t give us many details of their conversation, but Schenck says a question by the grief-stricken man haunted him.

Where the hell are the clergy?

I think, more aptly, we might need to be asking: Where are the Christians? But the problem is, I don’t think the Church yet knows what its position is on guns.

As we come out of a year where debates about gun rights and stories of mass shootings dominated the front pages, questions about the Church’s role in ending our nation’s plague of gun violence keep turning over in my head. People are dying every day in a genocide fueled by anger, narcissism and fear. The solution is likely multi-pronged and will require an honest, hard discussion about our culture of outrage, mental health treatment, and, yes, access to guns. This isn’t strictly a political issue — it’s a fight for our nation’s soul. But how can we begin to tackle those aspects honestly when so many Christians are ardent gun owners and members of the NRA, who find a way to weave their need for a gun into their theology?

That’s the question Schenck wrestles with in this bracing, thought-provoking documentary. A staunch Pro-Life advocate, Schenck has become one of the most highly regarded spiritual leaders in American evangelicalism. As we meet him, he’s beginning to question what the implications of his pro-life stance are on the topic of Christians and gun ownership, questions that gained new urgency when the Washington Navy Yard shooting broke out near his home in 2013. The film doesn’t delve deeply into politics but rather observes Schenck as he wrestles with forming a Christian theology of guns. Do Stand Your Ground laws have a place in the lives of those who are told to turn the other cheek and love their enemy? While Christians have a right to self defense and a duty to protect their families, is it right for them to be prepared to shoot to kill? Does the phrase The only thing that stops a bad man with a gun is a good man with a gun hold any water in a faith the believes no one is truly good? Do too many Christians let their views on guns be formed by the NRA and the Constitution instead of the Bible? And what about the uncomfortable truth that the topic of guns has a much different context depending on the color of your skin?

Schenck says that one of his flaws is that he is too fond of simple answers; he compares them to heroin, in that they make you feel good and they placate you. The answers we hear on gun ownership in the church are often simple ones — “Constitution gives me the right.” “I gotta protect my family.” Or, on the other side: “Take all guns away,” “Do better background checks.” But a theology of guns must ask tough questions that appeal to more than simply our legal rights. So many arguments are couched in fear — fear of the government, fear of others, fear of danger. When the Bible’s most repeated command is “Do not be afraid,” our tendency to cling to guns for protection takes on a new dimension (“So you need Jesus…and a side arm,” Schenck muses during one dialogue). When we more readily cite the Constitution instead of the Bible to give a reason for our right to bear arms, we have to ask whether we as Christians have misplaced our authority. And when the mere question of whether Christians should own guns comes up and we immediately get defensive and angry, maybe it’s time to question whether our trust is more in a gun than in God (“We must be very careful that in respecting the Second Amendment we don’t violate the Second Commandment,” the preacher speaks in a sermon).

This is an important conversation that we must be having in Christian community right now, but it’s not an easy one. Some of “The Armor of Light’s” most intense moments involve Schenck trying to start a discussion with congregations and local church leaders, and it’s revealing to see how quickly their posture turns defensive and how angry they become at the mere suggestion that this issue might be more complex than they think. One of the film’s most arresting moments — and possibly its most heartbreaking — involves a discussion between Schenck and fellow leaders of a pro-life alliance that turns into a shouting match over the subject. As a pro-life advocate whose constituents are mainly hard-core conservatives, Schenck risks losing funding if he’s “branded with the scarlet letter ‘L’ for liberal.” I’ve seen in my own life how hard it is to engage Christians on the subject of gun ownership. It quickly leads to screaming matches, angry social media posts, and broken relationships. But as people who agree to come together under a higher authority, wrestle with the truth and ask hard questions, we must be having this conversation. In order for us to move forward and heal our communities and do any good, we must first begin to wrap our arms around the problem at hand. And to do that, we have to start having tough discussions that may shatter our personal golden calves.

And action and leadership are exactly what the Church should be modeling on this subject. We forget that Christians weren’t always so closely aligned with the NRA and the Republican party, nor were they so quick to encourage people to be ready to kill or support retaliation. The film reminds us that the evangelical alignment with the Republican party is relatively new; prior to Reagan’s presidency, the majority of evangelicals were Democrats, many of whom were pacifists. I say this not to tell all conservative Christians to become liberals. But it’s a reminder to hold our political affiliations loosely and remember that Christians are called not to cling to political sides but to model love, mercy, grace and hope in our communities — not to be people spouting fear, anger and isolationism. Our theology trumps our politics. And while I have no clue what a solution to gun violence looks like, I know that Christians must play an important role in that solution — and that their answer must be rooted not in the Constitution or American history, but in the Word of God.

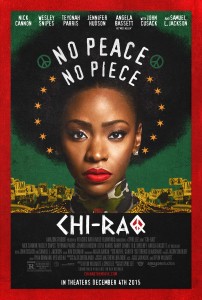

Another recent film reminded me of the Church’s role in moving our communities toward healing. Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq” (now available on Amazon Prime, DVD and Blu-Ray) is not a film I would easily recommend to many — the sexual content and language might keep some away. And from a quality perspective, I’m not quite so sure what I think about it. It’s a tonal mess, with broad, raunchy comedy smashing hard against didactic polemics and scenes of raw drama. And yet I think it’s the most energized Spike Lee’s been since “The 25th Hour,” and it might be the most passionate, raw expression of his creativity since “Do the Right Thing.” It’s a mess, but a glorious one. Lee is pissed off about the violence erupting in Chicago, and he allows that anger to boil over in this powerful, emotional movie.

It’s a timely film with a foundation that’s two millennia old. “Chi-Raq” is an adaptation of Aristophanes’ comedy, in which the Spartan and Trojan women are so tired of war claiming the lives of their men that they vow to withhold sex until they lay down their arms. Or, as the women of “Chi-Raq” crudely put it: “No Peace, No P***y.” The cause eventually goes worldwide and causes frustration not just among the gang members in inner-city Chicago but among the people involved in institutions that disenfranchise people; thrive on outrage; and put a higher value on the bottom line than on human lives. It as angry as anything Spike Lee’s ever done, but it’s also as funny, tragic and emotional as any of his best films. And while I’m sure the language and sexual content might turn some Christians viewers away, it features one of the most poignant and powerful looks at the role of the church in the urban community that I’ve seen.

John Cusack plays the pastor on an inner-city Chicago church. And while the women are busy encouraging ladies around the globe to close their legs until their men lay down their guns, he’s busy tending to the souls of the neighborhood. He comforts a woman who’s child was the innocent victim of a stray bullet. He delivers the most passionate, fiery on-screen sermon I’ve seen, calling his congregants to action in a screed against gang warfare, male posturing, institutional racism, the gun industry and our curdled culture that goes on for nearly 10 minutes. He leads members of his church on a march down the streets of Chicago. And he personally meets with one of the gang leaders, a rapper named Chi-Raq (Nick Cannon), to urge him to lay down his weapon and do the right thing.

The pastor can do this because this is his community. As Cusack’s character tells Chi-Raq, he grew up here. He knows the people. He’s their spiritual leaders. While the women are arguing for political change, he’s healing and encouraging his community, calling them to action. The movie argues that both efforts are essential.

Christians should absolutely be political. Christianity doesn’t exist in a vacuum — we need Christ-followers in every field, doing excellent work with attitudes of love and compassion. And that includes the political arena — Christians should not just be involved as voters but should also hold public office. But the local Church has a responsibility to its community and to people, both there and around the world. I’m proud to attend a church that takes that role seriously. The church I attend is small, but it has a major presence and involvement not just in our local neighborhood but in the large city (Detroit) we border.

But I think many Christians — including myself — immediately think our main role is to be political. When there’s a mass shooting, we leap to social media to Tweet about why the government should/shouldn’t take guns away. We align ourselves with Republicans and Democrats. We commit the same sin the New York Daily News called out our politicians for — we say our thoughts and prayers are with the victims (which is a good, right thing to do), but then we spend the rest of our time bickering and fighting online. We do it because a prayer and a tweet are easy — they require nothing of us. But tweets without love are worthless. And if thoughts without action are meaningless, I think angry Facebook/Twitter posts without action are even moreso. We lament that the world is broken. We ask God to heal our nation and our neighbors. We pray for a solution. All of these are good things to do. But we forget that, as Christians, we believe that part of that solution necessarily involves us acting as God’s hands in a wounded world.

Our nation is hurting. As Christians, we need to help it heal. We need to be comforting families and surrounding them with prayer — especially if they’re in our local communities. We need to look beyond our politics to see what might be in place that is causing this hurt, this anger and this fear. We need to be shouting a Gospel of love in a culture that is screaming outrage. We should not be known for our anger unless it’s directed at sin and death. We should be known as people who love their enemies and do not fear them, but rather serve and even lay down our lives for them. We must have better eyes to see the hurting brothers and sisters worshiping alongside us, for tomorrow’s shooter is today a wounded soul in need of help. We must have honest conversations about our toxic culture, the correct place of guns, mental health care and the power of hope. We must lay down our political shield, look honestly at our world and find a way to best saturate it with the healing love of the Gospel.

The church can heal the community. The church can help the community. The church can pray for the community. And I’m thankful for the believers who are already involved in counseling the community, finding a solution to violence and urging congregants to pursue peace and love. But there’s so much work to be done. Until we’re known more for loving our enemies than clinging to our guns, we have a problem. Until we are praying with those who might not share our political views instead of casting judgement on them, we have a problem. Until we are openly weeping because people in our nation die every day, we have a problem.

We can do better, and we must.