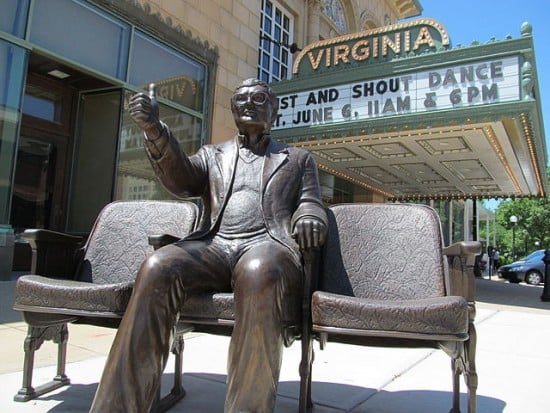

Today marks the third anniversary of Roger Ebert’s death. In honor, I’m re-posting this entry that I wrote for my old, now-defunct blog.

What does it mean to love movies? It does not mean to sit mindlessly and blissfully before the screen. It means to believe, first of all, that they are worth the time. That to see three movies during a routine workday or thirty movies a week at a film festival is a good job to have. That your mood when you enter the theater is not very important, because the task of every movie is to try to change how you feel and think during its running time. That it is not important to have a “good time,” but very important not to have your time wasted. That on occasion you have sat before the screen and been enraptured by the truth or beauty projected thereon. That although you may be more open to a movie whose message (if it has one) you agree with, you must be open to artistry and craftsmanship even in a movie you disagree with. A movie is not good because it arrives at conclusions you share, or bad because it does not. A movie is not about what it is about. It is about how it is about it: about the way it considers its subject matter, and about how its real subject may be quite different from the one it seems to provide. Therefore it is meaningless to prefer one genre over another. Yes, I “like” film noir more than Westerns, but that has nothing to do with any given noir or Western. If you do not “like” musicals or documentaries or silent films or foreign films or films in black and white, that is not an exercise of taste, but simply an indication that you have not yet evolved into the more compleat filmgoer that we all have waiting inside. — Roger Ebert

There are some people whose work influences you so much that you feel like you’ve known them, even though you’ve never met. There are a handful of people whose work has been so influencing on the ways I think and write that I feel a personal connection with them, even though we’ve never traded words or been in the same room. Among those ranks are Jim Henson, Walt Disney, CS Lewis and John Piper.

And Roger Ebert, whose work had a deep impact on my views of religion, philosophy and politics, but also — more concretely — on my love of movies, profession as a writer and part-time job/hobby as a film critic. It’s cliche by now to say that I wouldn’t be reviewing films if it weren’t for Ebert, and that’s true. But I also think my broader career as a writer is due to his wit, profundity and way with words.

I’m rare from others in that I didn’t really watch much of “Siskel & Ebert” or “At the Movies,” the TV shows that brought him to prominence. Sure, I knew of them. I knew what “Two Thumbs Up” meant, and I’d seen them trade barbs on talk shows. It was impossible to grow up in the ’80s and ’90s and not know about the bald guy and fat guy who argued about movies on TV. I knew enough to pay attention to Siskel and Ebert if they liked a movie, but I never could find the time to watch them regularly.

It wasn’t until I was in college, having a late-night conversation on AOL, that a friend and I were chatting about movies and they directed me towards Ebert’s website — this was the early days of the Internet, mind you, and I hadn’t even considered that a film critic would have their reviews posted for everyone outside of their readership area. I scrolled over, gave it a look and began visiting his site weekly.

It hit me at just the right time. I was just transitioning from community college to university, and had recently made up my mind to major in journalism. When considering a minor, I chose “film studies” on a whim, given how much I enjoyed movies. But as a kid who had been raised Baptist and shielded from a lot of movies because of their content, I found wading into deeper cinematic waters to be problematic, even terrifying. It wasn’t just that many of the American and foreign films that were considered “great” seemed to be over my head and hard to process; it was that many of the “great” movies — films that movie lovers held dear — had content that I had been told was bad. Was I going to learn to love movies at the expense of my soul? What was I to make of a movie like “Taxi Driver,” which moved me and got under my skin, but was soaked in foul language, dealt with lurid sexual content and ended in a blood bath?

It was Roger’s famous mantra: “A movie is not what about what it’s about, but how it’s about it” that taught me I needn’t be afraid of content, but rather willing to wrestle with it, engage it and question it. Without this motto, I would never have been ready to explore films that rattled me to my core and left me shaken. It was Ebert who, through his website and books, held my hand as I nervously waded into studying film. Aside from Jeffrey Overstreet’s “Through a Screen Darkly,” I don’t know that any books had a more profound influence on me as a fledgling film critic than Ebert’s Great Movies series; his incredible collection of reviews and essays, “Awake in the Dark;” and his wonderful book of negative reviews, “I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie.” I will fully cop to sitting to write a review and asking myself, “what would Ebert think about this review?”

It was Ebert who taught me that “all bad movies are depressing, no good movies are,” and that “no good movie is too long, and no bad movie is short enough.” I found myself searching his archives for reviews of old movies, spending days reading his thoughts on them to better understand what I liked or challenge myself to revisit a masterpiece I may have shrugged off. I remember reading his review of James Cameron’s “Aliens” and being stunned that he could write about how depressed and exhausted it made him, yet giving the film 3.5 stars because he respected that it was able to make him feel that way.

Ebert was fond of repeating Robert Warshow’s quote that “A man goes to the movies. The critic must be honest enough to admit that he is that man,” and it’s a truth I’ve had to return to many times. When an admittedly bad movie engages me, when I make a mistake in judgement or when I simply have no other defense for a movie but “I enjoyed it,” it was this quote that reminded me that film is subjective, and you can’t dismiss your own personal make-up in your approach.

Ebert’s “Little Movie Glossary” was a wonderful and funny reminder of the tropes movies continue to trot out, and it celebrated those formulas as much as it mocked them. Ebert taught me to never look down at a movie, but to approach it on its level; to try not to let my attitude when I walk into a theater affect my view of that movie; to embrace other passions and let them inform my criticism. He let me know that it was okay to savage a truly horrible film, but that joy in film criticism comes from championing the truly great.

But, above all, it was the wit, intelligence and humanity that filled every one of his pieces. He wasn’t a cold, overly intellectual critic. He taught me that film criticism was as much an art as film-making. His language was conversational, even when he was peppering his reviews with references to classic novels, poems and philosophers.

When cancer took his physical voice in the early 2000s, Ebert’s access to the Internet gave him another. His writing changed and took on new depth. I was moved by his frank discussions about life after his surgery, about how he missed the simple joy of eating food and how he knew exactly what his new face looked like. His writing on politics — which he said always started from “a place of kindness” — were crucial to me as I softened and changed my own political views. I looked forward to his blog postings even more than I did his film reviews, and I loved the humor and warmth with which he tackled everything from his views on evolution to his love for Steak N’ Shake. Ebert didn’t share my faith, but he was a kind atheist/agnostic (even if he hated those terms). He never begrudged anyone for having a faith he couldn’t share, and I’ll admit that his posts on his lack of faith often made me stop and question — questions that were crucial in eventually affirming my faith.

I’m sad that I’ll never read another new review by Roger Ebert. I’m sad that his excellent memoir, “Life Itself,” is the last book I’ll ever read by him. I’m sad that I never will get to meet him, and that I’ll never be able to tell him how his writing influenced me, and made me want to be a better writer.

The film adaptation of “Life Itself” by Steve James is currently streaming on Netflix.