“Every day was the day you were going to die. It was pretty much a place of hell and despair with no hope.”

“Every day was the day you were going to die. It was pretty much a place of hell and despair with no hope.”

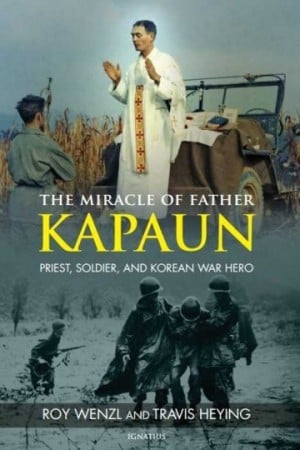

That’s how the former Allied soldiers, interviewed by Wichita Eagle reporters Roy Wenzl and Travis Heying for their Christopher Award-winning book “The Miracle of Father Kapaun,” described their lives in prisoner of war camps run by the North Koreans and Chinese during the Korean War. These soldiers endured freezing temperatures, starvation, and blood-sucking lice, which caused their health to deteriorate even faster.

One person who did all he could to keep these soldiers from death was U.S. Army chaplain Father Emil Kapaun. By the time he got to the POW camp, Father Kapaun already had a reputation as a fearless and holy leader.

Courage Under Fire

During an interview on “Christopher Closeup,” Wenzl explained, ” Father Kapaun’s Eighth Calvary Regiment had been in a number of gruesome big battles. He ran around and rescued the wounded, almost recklessly, dragging them back to safety when they might have been shot pretty far outside the foxholes. That’s part of the reason that people were so willing to follow him.”

Another reason occurred soon after Father Kapaun’s regiment was captured in November 1950. While the the American GIs were being marched to the POW camp, Father Kapaun saw a Chinese soldier with a rifle pointed at the head of Sgt. Herb Miller, who was lying in a ditch with a broken ankle. It was routine for the Chinese to execute enemy soldiers who were wounded.

Wenzl said, “Father Kapaun breaks away from his captors, strides over, brushes the Chinese soldier’s rifle up in the air, then leans down right in front of him, picks the sergeant up and carries him away. And the sergeant’s still alive; it’s Herb Miller from Pulaski, New York. He says, ‘I thought both of us were gonna get shot in the back as he carried us away but the Chinese soldier just stood there. He didn’t know what to make of this.’”

A Spirit of Defiance, Purpose, and Faith

Life in the camp was brutal, but once again, Father Kapaun provided material relief, moral leadership, and spiritual guidance. For instance, the Chinese and North Koreans only gave their captives a handful of birdseed to eat daily. Despite starving himself, Father Kapaun often gave his seeds away to set an example of sharing.

The Allies also didn’t receive any water to drink from their captors, so they scraped snow and ice off the ground to hydrate themselves. As a result of ingesting unclean water, they often got dysentery.

Because of his youth working on a farm, Father Kapaun found a solution. Wenzl said, “He took roofing tin from bombed out buildings and banged rocks on it and formed them into bowls that they could use as little cooking pots.” That saved lives because it allowed them to boil water before drinking it. And for the soldiers who did suffer from dysentery, Father Kapaun would hand wash their underwear, demonstrating that absolutely no act of service was beneath him.

Father Kapaun also boosted the Allies’ morale by defying the brainwashing techniques their communist captors employed on them. “He would literally stand up,” noted Wenzl, “and say, ‘What you’re telling us is a bunch of lies. It’s not true!’”

The practice of Catholic prayers and rituals became another way to defy the enemy. Wenzl said, “The guards banned any sort of religious services, so Father would sneak around at night, go into the huts and say the rosary. The Protestants and the Jews and the agnostics would pray the rosary because it was a way to support him. [Those prayers were] also a way to rally the men, to say, ‘We’re soldiers. We can’t give up.’ A lot of those guys committed suicide. They didn’t have any coats or blankets and it was 20, 30, 40 below. All you had to do to commit suicide was roll away from your friends, get away from their warmth, and you were gone the next morning. He was trying to keep them alive by creating some sort of spirit of defiance and purpose.”

The camp’s communist commanders saw Father Kapaun as a threat, so they capitalized on the situation when he grew weak and sick. Wenzl said, “The Chinese had this thing that they called a hospital, but the soldiers called it the ‘Death House’ because the Chinese used it to isolate prisoners who were on the verge of death anyway. That’s what they did with Fr. Kapaun; they isolated him. He died a couple of days after they did that. But when the Chinese decided to cart him off to the Death House, the allied soldiers tried to fight at first. Father told them to stop. He didn’t want them getting in trouble. Then the soldiers volunteered to carry him, as sort of an honor guard themselves, to his own death. And on the way in to the doorway of the Death House, Robert Wood – one of the soldiers I interviewed – was one of these guys carrying him. Father’s hand came up off of the stretcher and he blessed the Chinese guards who were participating in his murder and he asked their forgiveness, and then said, ‘Father, forgive them.’”

Christ Was His Role Model

Where did Father Kapaun find the strength and character to do this kind of thing? For Wenzl, the answer is obvious: “When you read his early sermons as a young priest, it’s clear he had spent a lot of time reading the New Testament. So all of these actions – showing by example, the specific things that he said to people – it was clear that he had in his head long before he went to war, that if there was ever some sort of world disaster where people really needed somebody that they could count on, that it would be him. And he already had in mind how he would do that which was, not with a lot of words, but by example. So I think Christ was his model.”

Though it took Father Kapaun’s friends 50 years to get him posthumously recognized with the Medal of Honor, it finally happened in 2013. In addition, the chaplain is also on the road to sainthood after several seemingly-incurable patients were healed following prayers for his intercession. Wenzl notes that many of the people supporting Father Kapaun’s cause for sainthood are Protestants who are “baffled about why this guy hasn’t been named a saint.” It seems that even in death, Father Kapaun is crossing denominational lines just like he did in life.

Wenzl believes that Father Kapaun’s influence will continue because of the way he lived. He concluded, “He would climb into holes and dig latrines without saying a word. He would get right beside these guys and get dirty with them, and then run around and rescue the wounded. People saw this and they thought of him, not as a captain, which he was – and not as a priest, which he was. They thought of him as ‘He’s that guy that we’ll do anything for because he would do anything for us.’”

(To listen to my full interview with Roy Wenzl about “The Miracle of Father Kapaun,” click the podcast link):

Christopher Closeup podcast – Guest: Roy Wenzl