You’ve no doubt encountered Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence.” It begins with:

To see a world in a grain of sand,

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

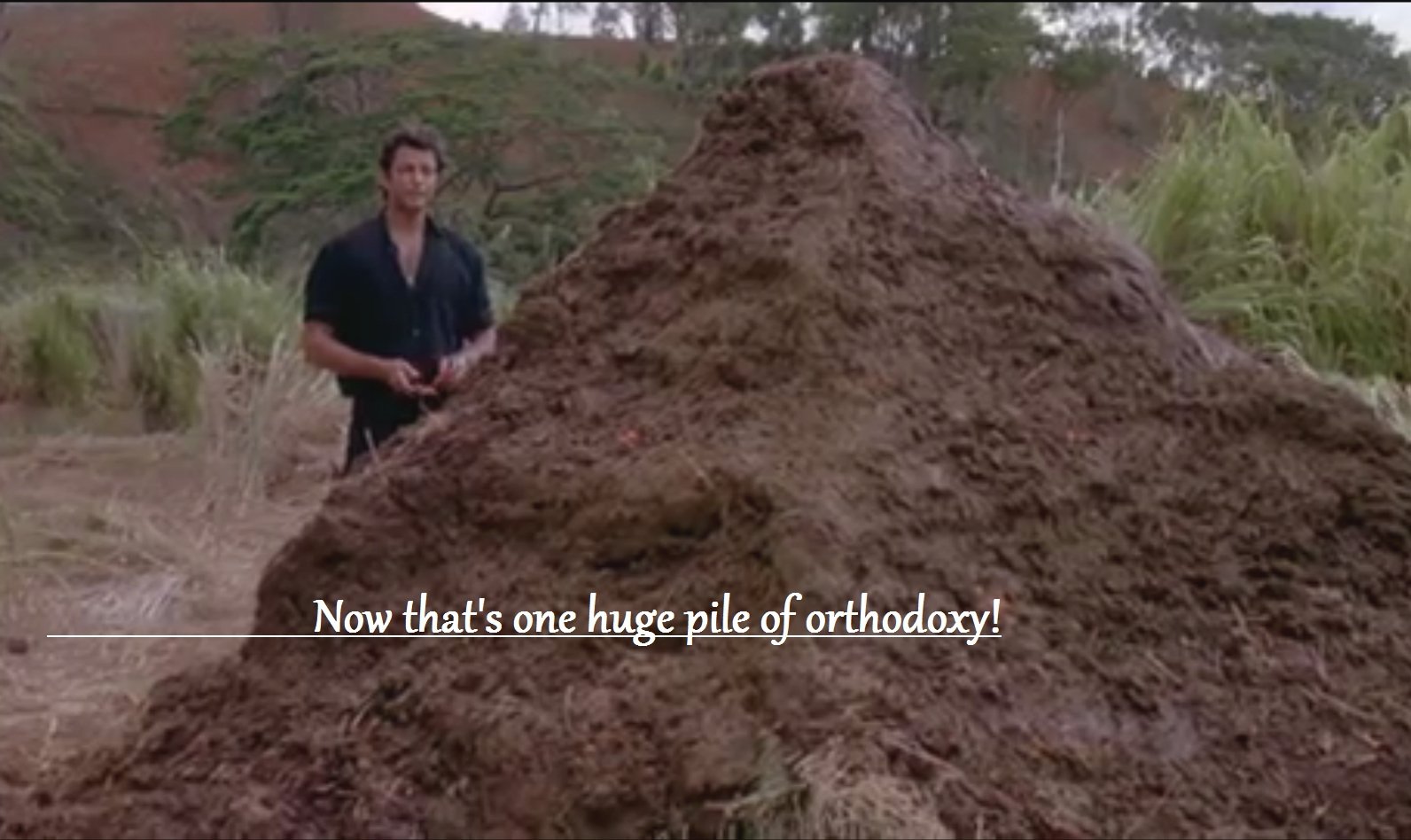

I’ve stepped into a variation upon this theme. It appears in the remarkable work, Infinity and Perspective, by Karsten Harries (who seems to be a former student of Louis Dupre). Take in the full glory of my serendipity with this photo and its caption (not just the text on it):

In some ways this statement makes Timothy Treadwell’s nature mysticism more palatable and orthodox than it seemed when I first watched Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man:

“It’s her life!”

Now, Infinity and Pespective roots the origins of (post-)modernity, plus its their critique, in the thought of Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464).

Harries notes how this is due to a shift in metaphor usage (one that encourages my mash-up above) that occurs in the writings of Cusanus (not Copernicus [Kopernik in the Polish original], not Galileo, not Bruno):

“But what about Cusanus’s transference of this metaphor [of an infinite sphere whose center is nowhere and whose circumference is everywhere] from God to the cosmos? I suspect that to Cusanus it seemed only obvious. As a Christian thinker he believed that everything created has its origin and measure in God. As he puts it in book 2, chapter 2 [of On Learned Ignorance] “every created thing is, as it were, a finite infinity or a created god” (II.2, p. 93). Our tree, for example, is such a finite infinity. Like every part of creation it shares, if Cusanus is right, in infinity. It is a contracted infinity.”

He continues:

“Similarly Cusanus understands the universe as such a finite infinite: like God in its infinity, unlike God in that instead of divine unity, we now have a multiplicity, a manifold spread out in space and time. If both oneness and difference are accepted, not only will the metaphor’s transference from God to the cosmos seem justified; but, since the metaphor joins extension and infinity, it can be said that it does greater justice to the cosmos than to God, who is beyond extension.”

How much more exciting is this than our heresy of the definite, bounded, and measurable? By this I mean Robert F. Kennedy’s (Memory eternal!) heresy of “What gets measured, matters.”