My wife and I are doing our best to revive our practice of watching films in the evening. This is not all that easy when you try to do it with a five, a three, and a one year old. We were forced to grab something that would be relatively adequate for the whole audience.

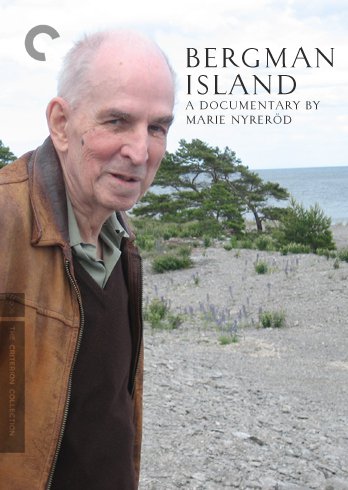

Our choice was the documentary film Bergman’s Island. We figured watching a film about an old lecherous Swedish man living out his last days on a lonely island with beautiful vistas would do minimal harm. We were right.

It took our five year old about twenty minutes to fall asleep while the three year old stuck around through the whole thing continually asking “Why?” (This is the perennial philosophical question. And people wonder why philosophers are frequently so annoying…).

It was the same question Bergman was attempting to answer about his own beliefs throughout the film. It’s been said his trilogy was an attempt to murder the cruel Lutheran God of his father on the screen. But the issue of God wouldn’t stay dead, especially after the death of Ingmar’s last wife. She must have been a saintly woman because she survived with him for twenty-four years.

Her mysterious presence in his life after her death made Bergman doubt his own doubt. It is a testament to the possibility that even for irascible Scandinavian loners love is stronger than death. At one point in the documentary the filmmaker plays a clip from his film Private Confessions, which appears to be based upon this novel of his.

Here is the monologue in case you missed some part of it.

“Don’t use the word ‘God’. Say ‘holiness’. There’s holiness in everyone. Human holiness. Everything else is attributes, disguise – manifestation and trickery. You can never capture or figure out human holiness. At the same time, it’s something to cling to. Something tangible, lasting unto death. [Bach’s ‘Jesu, joy of man’s desiring’ is heard] Whatever happens then is hidden from us. Only poets, musicians and saints may depict that which we can but discern: the inconceivable. They’ve seen, known, understood – not fully, but in fragments. For me, it’s a comfort to think about human holiness.”

This is obviously not meant as a dogmatic statement, so relax and countenance the possibility that you might learn something about your own tradition by listening to those who are on its peripheries, or even outside of it. There’s a wonderful ambiguity about the denial the use of the word God in the first sentence (if you actually bother to read the rest of it and struggle with what he’s attempting to convey).

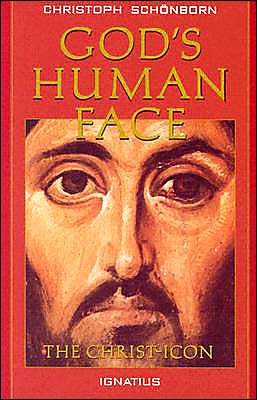

The interesting part for me is how Bergman points to something here that’s central to a Catholic way of approaching God: the mystery of human holiness.

I’ve written here how much the influence of my own teachers helped me grapple with the inconceivable. The encounter with holiness is also very much at the heart of Giussani’s writings (and possibly the pope’s interviews?). It’s also a thread that was very important to the writings of von Balthasar, especially in the second and third volumes of his Glory of the Lord, plus the Bernanos, Carmelite Sisters (Thérèse and Elizabeth), and Schneider biographies. These strands in his thought are developed by two great Anglican scholars, Mark McIntosh and Victoria S. Harrison, in the volumes Christology from Within and The Apologetic Value of Human Holiness respectively.

Several posts about the work of Dariusz Karlowicz in Cosmos the in Lost also demonstrate how much the tradition of Christian witness owes to an older tradition of philosophical witness. So I suppose this is a case of both/and. The witness of human holiness is a centrally Christian way of seeing things because it was taken over from other traditions after the appearance the mystery of God made man .

All in all, perhaps Nietzsche was right when he said he’d be more inclined toward returning to his own Lutheran Christian roots if Christ’s disciples “looked more saved”?

It seems even the Lutheran tradition, with its strong emphasis on the notion of Deus absconditus, recovered some of this tradition after it produced extraordinary witnesses during World War II.

While you’re at it take a look at our TOP 10 book lists about the following topics: recent theology, poetry, novels, heaven and hell, religion and world politics, and, last but not least, science.