Early Christian history is usually presented as the parade of a motley crew of peasants, slaves, manual laborers, that is, the impoverished and uneducated masses. We imagine them to be the equivalent of our local labor organizers, homeless, and hipsters; folks to whom most First World people can’t relate.

Curiously enough there is a consensus between the detractors of Christianity (Engels, Marx, NIetzsche) and it boosters (Deismann, Troeltsch, Rauschenbusch) regarding this detail of Christian history. The only difference is that the boosters want to call their contemporaries back to a pure pre-Constantinian (communist or Anabaptist) past, whereas the detractors, usually following on the coattails of Nietzsche, want their contemporaries to escape from the soiled chains of a resentful slave-mentality.

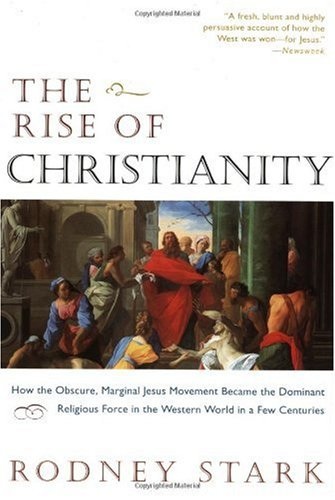

Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity rains on both of these parades. He notes how the recent (last fifty years or so) scholarly consensus is a return to an earlier (pre-19th century) consensus about the early Church as a movement full of well-educated and well-placed urban dwellers (See: Wayne A. Meeks, The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul, 1983).

Stark draws the following historical conclusions from this historical fact:

“Finally, what difference does it make whether early Christianity was a movement of the relatively privileged or of the downtrodden? In my judgment it matters a great deal. Had Christianity actually been a proletarian movement, it strikes me that the state necessarily would have responded to it as a political threat rather than simply as an illicit religion.”

In other words the early Christians had friends and relatives in high places who made sure the lions were being fed with unbaptized food.

The implications for Modern day Christianity are, I believe, even more interesting. If these conclusions stand the test of time (there is no indication they won’t), then we’ve always had (to borrow a book title from Ron Sider) rich Christians in an age of hunger. This leveling out of the sociological differences means there are more similarities between the Patristic age and ours. We might be best served by learning from the comprehensive Church aid and wealth redistribution programs of those times, which drove Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate crazy:

“Whilst the pagan priests neglect the poor, the hated Galileans devote themselves to works of charity, and by a display of false compassion have established and given effect to their pernicious errors. See their love-feasts, and their tables spread for the indigent. Such practice is common among them, and causes a contempt for our gods.”

Real Church history always is a lot more interesting, challenging, and perhaps kinder to Constantine, but more about that tomorrow.

Early Christianity was a lot more like this than you suspected.