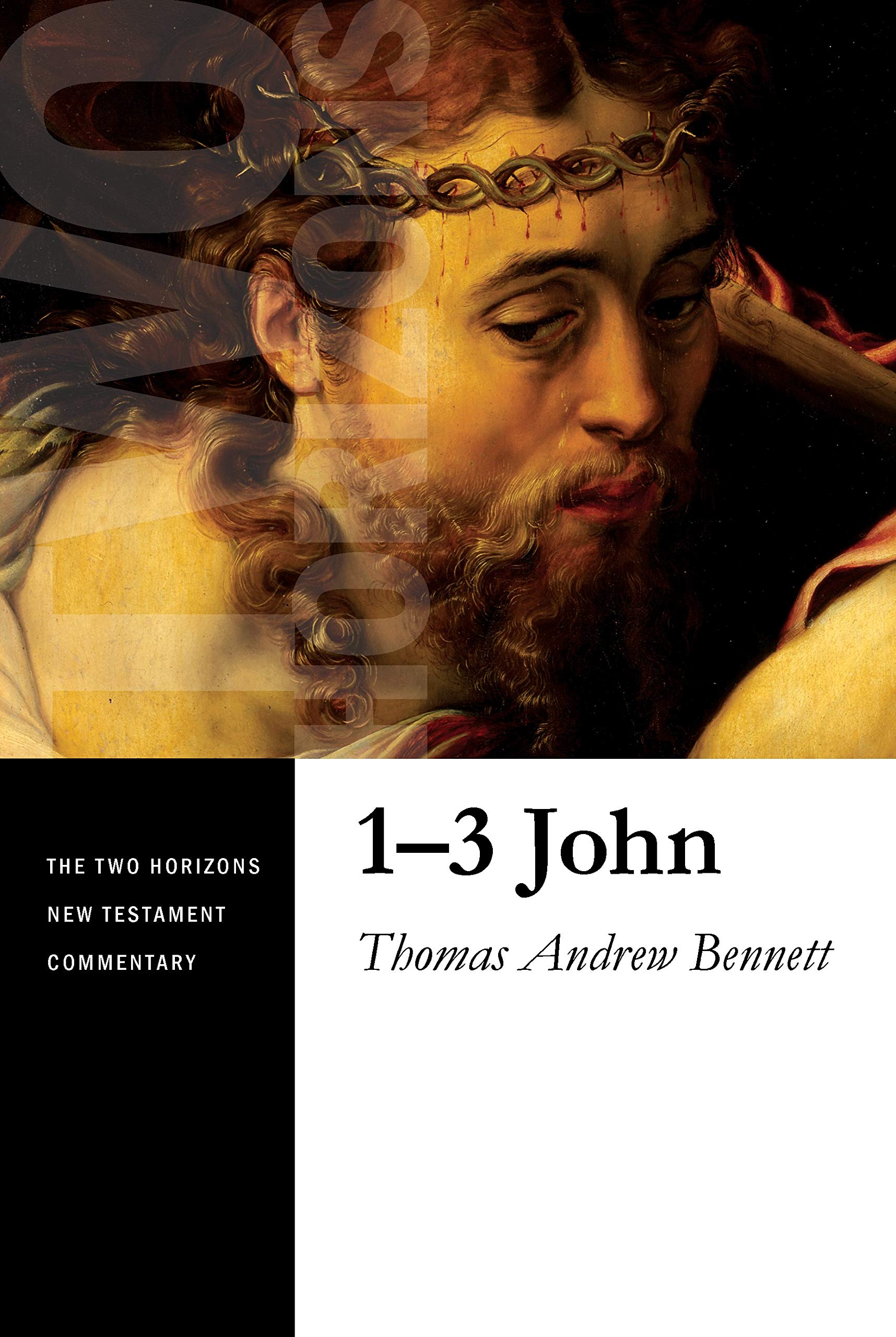

Dr. Thomas Andrew Bennett has published the 1-3 John volume in the Two Horizons New Testament series. Eerdmans kindly sent me a copy and I appreciated some of Bennett’s fresh thinking on approaching these letters. In the past, scholars have spent a ridiculous amount of time and energy “reconstructing” the so-called Johannine community, and then fitting 1-3 John into elaborate situational theories. Is that the best way to approach these texts? Bennett says “no.” I asked Bennett to write up some thoughts on this—enjoy!

Taking Back 1-3 John for the Church (Thomas Andrew Bennett)

The Problem

When I began seminary in 2005, the crumbling conventional wisdom was that the job of biblical studies was—through the careful application of historical-critical methods—to discover “what really happened.” The assumption was an academic (and secular) one: the Bible, like any other ancient document, is riddled with errors and fantasies and the job of the academic study of the text was to separate truth from fiction, cross over the gaps of history, mine the texts and whatever archeological findings to grasp once and for all what the biblical authors were hiding and what it all meant. The job of the preacher, then, was to sort through the assured findings of modern scholarship and figure out what it might mean now.

It was a disaster.

Seminarians who enjoyed this kind of study would give up quickly on actually serving the church, would take the academic track, and produce more volumes trying to figure out whether Jonah was a fairy tale (Consensus: yes), if it really took three days to cross Nineveh on foot in ~750 BCE (Consensus: it didn’t), and if there was a sea creature capable of sustaining human life in its belly (Consensus: there’s not). The seminarians who wished to preach preached, but did so mostly ignoring the work of their former classmates-turned-PhDs.

I say the conventional wisdom was “crumbling” because a cadre of ecumenical and confessing scholars were busy taking a sledgehammer to it on account of the revolutionary notion that the Bible should be for the church and that whatever scholars are doing with it should be of benefit to real, practicing Christians. The goal was not to leave the search for the truth behind, but to make it subservient to the “theological interpretation of Scripture,” that is, Scripture study that develops actual knowledge of and love for the God the texts were pointing out.

A noble end, to be sure, but it is taking some time to work out exactly how this should all work. And, over the last twenty or so years, everything from the academically rigorous approaches to methods mined from lay study have been tried: attending to the church Fathers, reinvigorating allegorical exegesis, spiritual exegesis, the canonical approach, etc. My own approach is highly syncretic, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

The result has been extremely promising. Fresh (or freshly recovered) ways of engaging texts have begun leading to whole new vistas of bible reading that nourishes the life of faith. Sometimes classical historical methods are tossed by the wayside; sometimes they are integrated with others; sometimes they take center stage. What drives theological interpretation and ultimately unifies it is its creedalism. All theological interpretation assumes from the outset that the Bible is meant to bless and nurture and convict and affirm readers because it testifies to the Triune God, the Father who sends the Son, the Son who, in the person of Jesus of Nazareth fully reveals the divine nature, and the Holy Spirit, who vivifies, guides, and empowers the church to witness to the world. When interpretation leads us to know and worship and love this God, there is a good chance that it is aiming in the right direction. Now, what does all this have to do with 1-3 John?

The Sermon and the Letters

1-3 John are some of the more enigmatic texts in the New Testament. 1 John has usually been classified as a letter, but it doesn’t read like one. 2 and 3 John are very short missives to a Patroness and her church and to “Gaius” and his church respectively. Moreover, these three texts bear strong linguistic and thematic links to the fourth gospel and Revelation. The church traditionally believed that “John,” the beloved disciple who followed Jesus and knew him wrote 1-3 John to the small churches in and near Ephesus where he lived and preached. But as we have just seen, what interested modern scholarship was not what the texts say, but what they hide. Who was John really? Was it really the same person who wrote the gospel? What kind of community did he lead? What did they believe and how was it different from churches Paul founded? Did the author really know Jesus? Why is the fourth gospel so different from the synoptics and what does that mean for 1-3 John? What occasioned 1 John? Who were the secessionists in 1 John 2:19 and why did they leave? The questions multiply themselves, not in the least part because, apart from 1-3 John, the Gospel of John, and Revelation, we have zero historical evidence on which to rely.

And so the most elaborate speculations were raised. 1 John is a commentary on the fourth gospel, meant to address theological problems raised by its idiosyncrasies. No, 1 John is a warning to churches not to succumb to incipient Docetism. No, 1 John is a manual written to identify heretics. No, 1 John gives us insight into the theological beliefs of the “Johannine community.” And what of 2 and 3 John? Of little note and certainly no historical value except insofar as they might have been cover letters for the main tract. All this is of incredible interest, no doubt, but not unfortunately to preachers and Christians who thought that there might be some Eternal Life to be gleaned from texts in which, unbelievably and incomprehensibly we are told, “Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love” (1 John 4:8). So how does the church take 1-3 John back?

The Solution

My commentary on 1-3 John proceeds from two closely related assumptions. The first is theological: because the church past, present, and future is One in the Spirit, the same Spirit who inspired John—whoever he (or she or they) may have been—to write these texts lives in the community of faith today and breathes into us the same Life. Because we share the same Spirit, 1-3 John is just as much to us as it is to those who first received it. You see, from a theological perspective, that is, from an ontological one, we are them and they are us. There are not “Johannine Christians” and “Pauline Christians,” there are just all those who share in the Spirit. Whatever was written was not written “for them” so we can find out how it might still be “for us.” No, it was written to us today because God the Holy Spirit binds us and makes us catholic.

The second assumption is philosophical: the text and only the text is the arbiter of meaning. Meaning is not “what really happened.” The meaning is the portrait of God that this text paints. This bears some further explanation. 20thCentury linguistic philosopher Paul Ricoeur developed a theory of meaning that I’ve called the “hypothesis of the text.”[1] Ricoeur thinks that every text, really every piece of art, projects a novel world. By attending closely to language, syntax, history, culture, etc., the reader can function as a kind of scientist, projecting what sort of world the text evokes. In effect, every interpretation of a text is a hypothesis. This text of this world is like this and not like that for reasons, a, b, and c. Ricoeur stands on the shoulders of Hans Georg Gadamer, an early 20th Century theorist who suggested something similar, that every text projects a horizon and that we bring our own horizon to it. Interpretation takes place when the horizon of the text begins to merge with and push back and be corrected by the one(s) we bring. When we bring this philosophical perspective to 1-3 John our concerns are less about what really happened and a lot more about Who is God in 1 John? And who does this text say we are? And how is that the same or different from what we normally think? How does that compare and contrast with other biblical texts? And if we were to adopt 1 John’s vision, how would that change the way we live?

Such an approach is no less academically rigorous than hard-nosed historicism. It might even be more so since it compels us to listen to the Fathers and contemporary sciences and literature and Greek and any other possible resource that might give us a handle on the world John tells. My prayer is that such an approach can give 1-3 John back to the church, back to sermons, that it can once again speak the truth to us now. And in that, I pray, we may once again be shocked by and conformed and united to the God who is love and so join in the storied and faithful communion of the saints.

[1] See Thomas Andrew Bennett, “Paul Ricoeur and the Hypothesis of the Text in Theological

Interpretation,” JTI 5 (2011): 211-30.

NKG: Check out Bennett’s new book