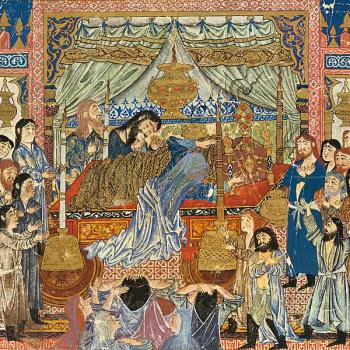

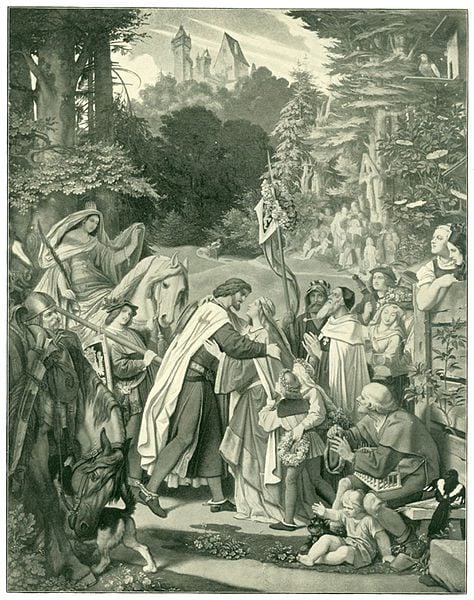

“Die Rückkehr des Grafen von Gleichen” (1864)

(“The Return of Count von Gleichen”)

He greets the wife that he had left behind in Europe when he left for the Crusades. Their two children stand by her side. Behind him, to the left, the sultan’s daughter sits on her horse.

All the way back in the 1990s, I wrote a few lines in the book Offenders for a Word about Christian polygamy:

The sixth century Arab Christian kings of Lakhm and Ghassan were polygamists, for instance, as were the contemporary Christians of Ethiopia. Pope Clement VII, faced with the threat of a continent-dividing divorce, considered bigamy as a solution to the problem of Henry VIII. Was he, with such thoughts, flirting with becoming a non-Christian? Did Martin Luther cease to be a Christian when he made the same suggestion, in September 1531, to King Henry’s envoy, Robert Barnes? Nearly a decade later, Luther counselled Philip of Hesse to take Margaret von der Sale as a second wife. He justified the idea from the Old Testament, as the Mormons would in a later century. Furthermore, he suggested public denial. (Generally, he had written in an earlier letter, he favored monogamy, remarking that “a Christian is not free to marry several wives unless God commands him to go beyond the liberty which is conditioned by love.”) But when Philip actually did marry Margaret in March of 1540, he did so—contrary to Luther’s counsel—publicly. Indeed, the marriage was performed by Philip’s Lutheran chaplain and in the presence of Luther’s chief lieutenants, Philipp Melanchthon and Martin Bucer. Needless to say, a storm of criticism broke out. Writing to John Frederick of Saxony on 10 June 1540, Luther declared, “I am not ashamed of the counsel I gave even if it should become known throughout the world. Because it is unpleasant, however, I should prefer, if possible, to have it kept quiet.” Was Luther a pagan? Did his associates, Bucer and Melanchthon, leave Christianity when they joined in Luther’s advice? Of course not. This was “Christian Polygamy in the Sixteenth Century,” as Elder Orson Pratt termed it in a well-informed 1853 article. Citing the statement by Luther, Melanchthon, and Bucer, to the effect that “the Gospel hath neither recalled nor forbid what was permitted in the law of Moses with respect to marriage,” Elder Pratt quite correctly concluded that the case of Philip of Hesse “proves most conclusively, that those Divines did sincerely believe it to be just as legal and lawful for a Christian to have two wives as to have one only.”

Here in Erfurt, I’ve come across another potentially interesting case:

There’s a legend of a Thuringian count who is sometimes called Ernst von Gleichen and sometimes Ludwig von Gleichen. In 1227, he went off on a crusade, leaving his wife behind with two small children.

He was taken captive, and was forced to serve as the slave to a sultan for many years. But the remarkably beautiful daughter of the sultan fell in love with him, promising to free him if he would take her with him and marry her. Since she was accustomed to the idea that a man could have several wives, the fact that he was already married didn’t bother her.

Fleeing aboard a boat, they made their way safely to Venice, and then from Venice to Rome. There, the Pope himself baptized the Muslim princess and granted permission to the Count to enter into a second marriage.

But, of course, there remained one problem. He was, in fact, already married. So, when he arrived at the fortress-seat of the von Gleichen counts, he praised the merits of the sultan’s daughter to his faithful surviving first wife. Without her, he said, he would have remained a slave. His wife would have been a widow, and his children orphans.

The two women hit it off well, so, as one German account says, “they shared the Count’s bed and, after their death, his tomb.” Legendary accounts speak of a “twice-wived [zweibeweibten] count” and of a “double marriage’ [Doppelehe].

(Click on the image to enlarge it. Click again to enlarge it further.)

The oldest material relic of this incident is said to be the von Gleichen tombstone in the Cathedral of Erfurt, shown above. It depicts a knight with two women, one on his right and one on his left. (Materials available in the Cathedral insist that the two women are the count’s single wife and his mother, but there appears to be no inscriptional evidence one way or the other.) There are also said to be several three-person beds preserved somewhere. (I don’t yet know where.) And, the pathway from Freudental, where the two women are said to have first met, to the ruins of the von Gleichen castle still bears the otherwise curious name of Türkenweg (roughly, “The Way of the Turk”–Turk being the loose term, along with Saracen, for the Muslim opponents of the Crusaders in the Middle Ages).

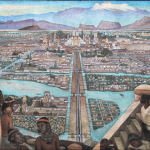

Later von Gleichen counts themselves told this story. Apparently, for example, a very large sixteenth-century tapestry in their castle, now mostly lost, depicted it. It also shows up in the writings of Goethe and the Brothers Grimm, in a drama by von Arnim, in an unfinished opera by Schubert, in many ballads, and on the walls of the Erfurt city hall.

Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, which tells the story of a knight returning from the Crusades, features two loving women (the faithfully waiting Rowena and the much more interesting and appealing “foreign,” “oriental,” Jewess, Rebecca). I wonder if Sir Walter might have been influenced by the tale of Count von Gleichen.

Posted from Erfurt, Germany