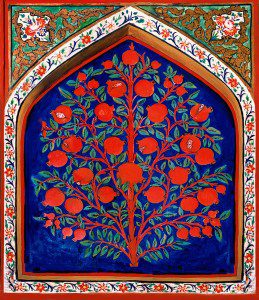

(Wikimedia Commons; click to enlarge)

Today’s reading, in my daily look at the Book of Mormon, is 1 Nephi 8.

This is among the best known chapters in the Book of Mormon, a chapter that has given us one of Mormonism’s most potent symbols, the Tree of Life.

I have a lot of other things to do today, and so, both for that reason and because of my self-imposed rule for this project, I need to resist the temptation to go on and on at length. I’m particularly interested in the Tree of Life, and have actually published on it in both Mormon Studies and Islamic Studies venues. (I might mention, by the way, that one of the last things produced by the old FARMS, by BYU’s Maxwell Institute before its abrupt embarkation upon a “new course,” was a volume entitled The Tree of Life: From Eden to Eternity that is well worth a look — and perhaps even worthy of purchase before it’s allowed to go out of print and into oblivion, if it hasn’t already done that.)

Today, though, I have a much more modest point in mind. I want to look at the language of 1 Nephi 8:2, where Lehi announces “Behold, I have dreamed a dream; or, in other words, I have seen a vision.”

I’ve sometimes used that verse to help beginning Arabic students understand what’s called a cognate accusative or, in Arabic, a tamyiiz.

The term cognate accusative refers to a sentence construction in which a noun that is “cognate” with (i.e., related to) a transitive verb is used as the object of that verb. (And it’s put in the accusative case to mark it as an object.) For example, darabahu darban shadidan (“He hit him a powerful hitting,” or “He hit him hard.”) The tri-consonantal root drb occurs both in the verb daraba (‘he hit” or “he struck”) and in the noun-object darb (a “hit,” a “strike,” a “hitting,” a “striking”).

It’s easy, of course, to see such a construction in Lehi’s “I have dreamed a dream.”

But I would argue that it’s also likely present — although, because of the peculiar history and hybrid character of English, it’s obscured — in Lehi’s “in other words, I have seen a vision.”

Why? Because, in the original, that phrase probably read “in other words, I have seen a seeing.”

In the currently-available Arabic translation of the verse, the translator avoided the cognate accusative in both phrases. This particular phrase currently reads shahadtu ru‘yan (“I have witnessed a vision” or, literally, “I have witnessed a seeing”), whereas the previous phrase reads ra’aytu hulman (“I have seen a dream”). But the second phrase could very easily have been rendered ra’aytu ru’yan (“I have seen a seeing/vision”), where the root r’y is repeated in both verb and noun-object: ra’aytu ru’yan.

This is hidden somewhat in the English because of the hybrid character of English since the Norman conquest of England in AD 1066. The Normans, although they were originally Germanic Northmen (i.e., Norsemen or Vikings), were thoroughly Frenchified by the later eleventh century, and so, accordingly, they brought their Norman French language with them and superimposed it as the language of the ruling class upon the Germanic language of the conquered Saxons who were already there.

This has contributed enormously to the richness of English vocabulary, in which a “higher” Latinate word–e.g. “Holy Spirit” or “manual” (from the Latin manus or “hand”) — often coexists with a “lower” Germanic equivalent still today — e.g., in “Holy Ghost” (compare German Geist and Latin spiritus) and in “handbook” (compare German Handbuch). The Latinate manuscript means precisely the same thing as the German Handschrift.)

How does this apply to 1 Nephi 8:2?

When the English rendering of that phrase says that Lehi has “seen a vision,” it’s using the Germanic verb “to see” (compare German sehen) with a word derived from Latin’s exact equivalent — videre (“to see”), from which comes visio (the act of “seeing”), from which comes our English word vision.

None of this is exactly a slam dunk proof of the Semitic antiquity of the Book of Mormon. After all, in Les Misérables Fantine sings “I dreamed a dream in time gone by.”

But it’s entirely consistent with the claim that the English Book of Mormon represents an originally Semitic underlying text.

And — a bonus benefit, an unintended by-product — using this illustration in my otherwise dry and sometimes intimidating classes on Arabic grammar has, I suspect, positively impacted my rating in student evaluations, in answer to the question about whether the instructor brings the Gospel into class discussions where appropriate. Who expected the Book of Mormon to be helpful in understanding Arabic sentence structure?