Dr. Melik: This morning for breakfast he requested something called “wheat germ, organic honey and tiger’s milk.”

Dr. Aragon: [chuckling] Oh, yes. Those are the charmed substances that some years ago were thought to contain life-preserving properties.

Dr. Melik: You mean there was no deep fat? No steak or cream pies or . . . hot fudge?

Dr. Aragon: Those were thought to be unhealthy . . . precisely the opposite of what we now know to be true.

Dr. Melik: Incredible.

From Woody Allen, Sleeper (1973)

On Saturday, in the context of a discussion about cosmic “worm holes,” I cautioned that “we should . . . be very careful about wedding theology or doctrine too closely to the changeable findings of whatever contemporary science has to say. (Surely that’s one of the lessons to be learned from the story of Galileo and the Aristotelians.)”

I think that I’ll expand upon that caution just a bit.

Science changes. In a very important sense, that’s not a weakness. On the contrary, it’s one of the great things about science. In fits and starts, at least, if not always quite smoothly, the scientific consensus adjusts itself to new findings and newly discovered facts. I like to think of science (to use a metaphor from analytic geometry) as asymptotic, as perhaps never altogether reaching the complete truth about physical reality but, over time — we hope! — drawing nearer and nearer to it.

We know now, for instance — or, anyhow, are pretty confident that we do — that there are no artificial canals on Mars, that four-humors medical theory is not true, that the steady-state theory of the universe is false, that continents drift, that ulcers are caused by the H. pylori bacterium rather than by stress, that leeching isn’t an effective treatment for disease, and that, contrary to M. Lamarck, parents don’t biologically pass acquired characteristics on to their offspring.

When I was younger, eggs were considered rather bad for your health, and egg consumption was a pretty good path to a heart attack. Since then, though — and without my really noticing it as it happened — eggs have made a comeback. Some argue that certain nutrients contained in eggs may actually help to lower the risk for heart disease.

The Ptolemaic model of the solar system was a vast improvement over what had gone before. Various refinements were made to it over the centuries, up to and including Tycho Brahe’s in the sixteenth century. In the end, though, the Copernican model replaced it. But that model wasn’t entirely satisfactory, either. Not until Kepler came along. However, there’s still plenty to be learned about our solar system — what should we make of Pluto, for example? and does the hypothetical Planet 9 really exist? — to say nothing of the inconceivably vast universe beyond.

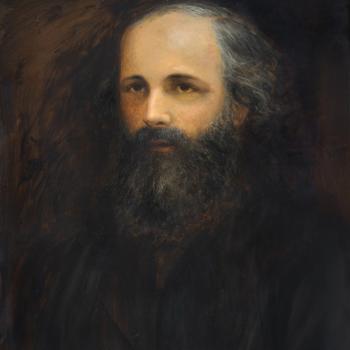

In the case of Galileo (1564-1642), the prominent historian of science and Galileo expert Stillman Drake (1910-1993) demonstrated, via many works, that the simplistic science-versus-religion morality play with which I grew up is historically untenable. There were many factors in Galileo’s trial and condemnation, but one of them was a conflict between Galileo and the powerfully entrenched Aristotelian philosophers who spoke for the scientific consensus of his era. In other words, it was really a battle between new science and old science, not between Christianity and science as such.

A substantial contributor to the dispute was the fact that the heliocentric system proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), whom we now justly venerate as the founder of the “Copernican Revolution,” didn’t really account with entire accuracy for the long-observed motions of the planets. In the contemporary language of the debate, it did not “save the appearances” noted by astronomers. For example, Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), the greatest observational astronomer of his day, could never bring himself to fully endorse or accept the Copernican model. Moreover, the laws of planetary motion proposed by Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), which, with their elliptical orbits, would eventually reconcile heliocentrism with observational astronomy, weren’t immediately accepted. Even Galileo ignored Kepler’s work.

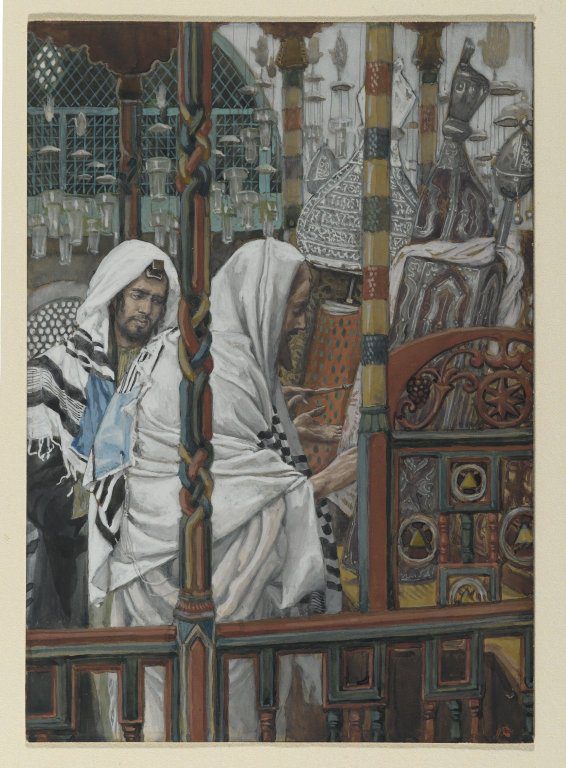

This — coupled with the fact that many astronomers, by this point, thought that they were simply constructing models that would fit the data, rather than discerning actual astronomical reality (which, they suspected, was beyond human capacity) — helps to make sense of the reaction of St. Robert Cardinal Bellarmine (1542-1641) to Galileo’s passionate advocacy of Copernicanism:

I say that if there were a true demonstration that the sun is at the center of the world and the earth in the third heaven, and that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun, then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary, and say rather that we do not understand them, than that what is demonstrated is false. But I will not believe that there is such a demonstration, until it is shown me. Nor is it the same to demonstrate that by supposing the sun to be at the center and the earth in heaven one can save the appearances, and to demonstrate that in truth the sun is at the center and the earth in heaven; for I believe the first demonstration may be available, but I have very great doubts about the second, and in case of doubt one must not abandon the Holy Scripture as interpreted by the Holy Fathers.

Unfortunately, many Catholic theologians had adopted Aristotelian science, which had been venerated by both pagans and Christians for many centuries, as essentially a part of their fundamental doctrine, which we now plainly see it was not. Thus, what should simply have been a debate between traditional science and the new science became, to the considerable harm of both science and religion, the concern of theologians and ecclesiastical leaders .

There is always a risk, even today, of illegitimately identifying a current and possibly transient scientific consensus (or political ideology, or other fashion) with the core doctrines of Christianity or the Restoration, such that those doctrines are vulnerable to the next scientific theory. Orson Pratt and some other Latter-day Saint writers of earlier generations, for example, seem to have toyed with the idea of a connection between the Holy Spirit and the universal “luminiferous ether” presupposed by many scientists. But the famous 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment rendered belief in the universal luminiferous ether untenable. Fortunately, Elder Pratt (who died in 1881) was aware that he was speculating and did not insist that his speculations be taken as official, binding doctrine.

That’s why I say that “we should . . . be very careful about wedding theology or doctrine too closely to the changeable findings of whatever contemporary science has to say.”