Many, many years ago, when I was still a graduate student at UCLA, my friend S. Kent Brown introduced me to Father Samir Khalil Samir SJ, an eminent authority on Christian Arabic literature, during some academic meetings in Claremont, California. Father Samir encouraged me — and that’s putting it rather mildly — to devote some attention to the writings of Arabic-speaking Christians, as well as to those of Muslims. Arabic Christianity, he lamented, fell between two stools among Western scholars. Academics who wanted to study Christianity focused on “Christian” languages such as Latin, Greek, Coptic, and even Armenian and Syriac. But academics who studied Arabic did so to focus on Islam.

I took his point to heart. And, so, when the Islamic Translation Series was well underway and we had also begun to publish some of the works of the great Rabbi Moses Maimonides, I thought it time to tackle the third part of the triad.

Here are the online descriptions of two of the books that we ultimately published:

Yahya ibn ’Adi, The Reformation of Morals, a parallel English-Arabic text translated by Sidney Griffith, of the Catholic University of America (2002)

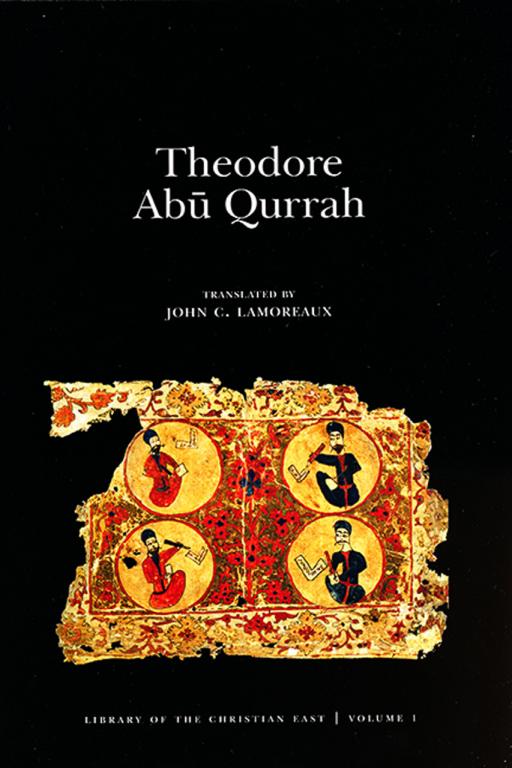

Theodore Abu Qurrah, translated by John C. Lamoreaux, of Southern Methodist University (2006)

Theodore Abu Qurrah, who died approximately 820 CE, was the Chalcedonian bishop of Haran and one of the first Arab Christian theologians. In numerous Arabic and Greek works, Abu Qurrah defended his faith from the challenges of Islam and the opponents of Chalcedon, and in doing so re-articulated traditional Christian teachings using the language and concepts of Muslim theologians. His writings provide an important witness to Christian thought in the early Islamic world.

This volume is the first English translation of nearly the complete corpus of Theodore Abu Qurrah’s works, with extensive notes on the Arabic and Greek texts. The translations are accompanied by a comprehensive introduction to Abu Qurrah’s life and writings. Specialists and nonspecialists alike will find this volume to be an accessible and important contribution to the history of Christian theology and early Islamic and Byzantine thought.

An amusing anecdote involving Sidney Griffith, the translator of Yahya ibn ’Adi’s The Reformation of Morals: Toward the end of my affiliation with the organization formerly known as the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), which had become the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, we decided to make a fundraising video explaining some of the organization’s accomplishments and goals. However, before it was finished there was a coup and I was forced out of the Institute. Some time thereafter, I ran into Father Griffith at an academic conference on the east coast. He knew nothing of the purge. We’ve always been friendly, and, in the course of our conversation, he told me of having been interviewed for that film. “I praised you extravagantly!” he told me, laughing. I thanked him, and I didn’t tell him that his positive comments about me had virtually guaranteed that he wouldn’t appear in the video. I’ve never seen it, but I’m informed that my private prophecy was accurate.