(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I published this article in the Deseret News back on 13 May 2010:

The earliest Christians didn’t believe in the New Testament. They couldn’t. It didn’t exist yet.

When Paul praises young Timothy because “from a child thou hast known the holy scriptures, which are able to make thee wise unto salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus” (2 Timothy 3:15), the only “holy scriptures” to which he can be referring are those contained in what Christians today call the Old Testament. When Paul proceeds to explain, in the following two verses, that “All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: That the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works,” he’s speaking of the Hebrew Bible. Or, if not, he’s referring to contemporary, ongoing revelation.

More than once, zealous “Bible-believing” Protestants have told me that, since Timothy already had enough scriptural material to “make (him) wise unto salvation” and to render him “perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works,” the Book of Mormon and modern revelation are unnecessary, redundant. They mistakenly assume that Paul was referring to the Bible as they know it. But, by their reasoning, the New Testament itself would seem to be superfluous, as well. (I generally congratulate such people on their apparent conversion to Judaism.)

2 Timothy was probably written about A.D. 64, at the end of Paul’s life. Most, if not all, of his other letters, obviously, had already been written and sent by then. But they hadn’t yet been gathered together, and the vast majority of Christian congregations — in an age without printing, modern transportation and easy communications — were probably unaware of them. (It’s virtually certain that they didn’t know of them all.) Moreover, the four gospels, the Revelation of John and many of the other New Testament epistles were very likely yet to be written.

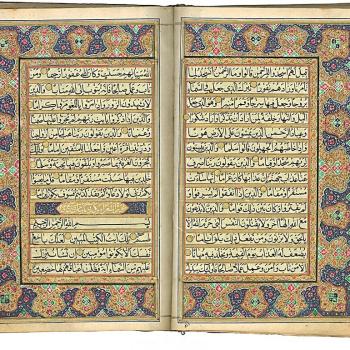

Nearly 20 years elapsed between the crucifixion of Christ and Paul’s first letter (1 Thessalonians, written in A.D. 52 or 53), and as many as 60 years or more may have passed before the last New Testament book was composed. (Some scholars would extend that interval to as much as 120 years.) And, then, even more time was still required to gather up the various books, copy them and establish a canon of scripture. In fact, complete texts of the New Testament were still relatively rare until Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the mid-15th century. Individuals seldom, if ever, owned their own copies; very few elite congregations possessed a complete set of the biblical writings. Moreover, most people were illiterate anyway. Given the rarity of books, illiteracy wasn’t a crippling liability, and the incentive to learn to read was relatively small. (Medieval European stained glass windows served a vital teaching function.)

What this tells us is that many generations of Christians lived and died without access to the New Testament in anything like the sense we know (and take for granted). So there must be something else that made them Christians, something prior to acceptance of the New Testament.

What was it? Plainly, it was the acceptance of Jesus Christ as Lord and Master. In the very earliest days of the Christian movement, such acceptance came via personal acquaintance with him, through hearing and receiving his teachings. Subsequently, it came through accepting the teachings of his apostles and other missionaries—still transmitted orally in almost all cases. Then, as the apostles and the earliest Christian disciples departed the scene, the task of passing on the doctrine of Jesus and the facts about his ministry, crucifixion and resurrection fell to those of the next generations. Sometimes they may have been equipped with a gospel or with an epistle or two, but, probably most often, they relied solely on oral tradition and memory.

This is another clue to what made people Christians in the earliest period: fellowship with the church and the disciples of Christ. As St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. ca. A.D. 108) put it in his post-apostolic time, in order to be a Christian, one had to be in fellowship with one’s Christian bishop. The church existed prior to the New Testament. It wrote the New Testament books and defined the canon. The Bible doesn’t establish the church; the church established the Bible.