(Wikimedia Commons)

Back in January 2018, David Grandy, now an emeritus professor of philosophy at Brigham Young University and the author, previously, of books on such topics as Magic, Mystery, and Science: The Occult in Western Civilization (2003), The Speed of Light: Constancy and Cosmos (2009), and Everyday Quantum Reality (2010), dropped off at my office a new, self-published book of his entitled Worlds Without Number: An LDS Perspective on Infinity.

I’ll be down in the San Diego area for several days in April, in connection with the public display of full-scale replica of Moses’s “Tabernacle in the Wilderness,” addressing (among other things) the concept of “sacred space.” So the following passage from Dr. Grandy’s book has come to my mind. He’s just been discussing the orientation of Jewish prayers to Jerusalem and of Muslim prayers to Mecca, Jacob’s experience at Bethel (on which, see Genesis 28:10-22; 35:9-15), and the idea of . . . well, sacred space:

This sensibility, that some places are intrinsically sacred, now seems quaint to Westerners who live in the thought world of Newtonian science. In that world, space is a neutral scaffolding for the occurrence of events, but the events themselves do not bleed over into the scaffolding. We consequently are inclined to insist that whatever meaning attends a place is that which we bring to it — our devotion or reverence. We alone, not the rocks or trees that were there at the time, memorialize and remember events. When therefore we read of the Pharisees’ attempt to quiet the jubilation that accompanied Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, we may find it hard to embrace the literal meaning of the Savior’s rejoinder: “I tell you that, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out.”

In ancient Israel, people were open to the idea of non-human nature being caught up in sacred events. “In the Psalms,” Jeanne Kay points out, “hills are girdled with you, valleys shout for joy (65:13-14), floods clap their hands, the whole earth worships God and sings praises to his name (66:1-4; 89:6).” Granted, some of these expressions are unmistakably poetic, but the poetry acknowledges nature’s desire to cry out. As Mircea Eliade put it “What we find when we place ourselves in the perspective of religious man of archaic societies is . . . that the existence of the world ‘means’ something, ‘wants to say’ something, that the world is neither mute nor opaque, that it is not an inert thing, without purpose or significance. For religious man, the cosmos ‘lives’ and ‘speaks.'” (29-30)

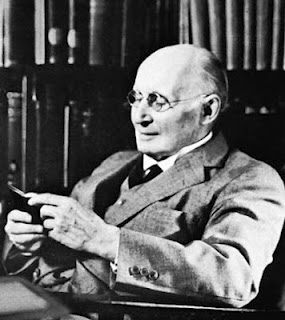

A deeply contrasting view is summarized (but not accepted) by the great Anglo-American philosopher-mathematician Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947) in his book Science and the Modern World, and quoted by Dr. Grandy:

These sensations [color, sound, etc.] are projected by the mind so as to clothe appropriate bodies in external nature. Thus the bodies are perceived as with qualities which in reality do not belong to them, which in fact are purely the offspring of the mind. Thus nature gets credit which should be reserved for ourselves: the rose for its scent: the nightingale of his song: and the sun for his radiance. The poets are entirely mistaken. They should address their lyrics to themselves, and should turn them into odes of self-congratulation on the excellency of the human mind. Nature is a dull affair, soundless, scentless, colourless; merely the hurrying of material, endlessly, meaninglessly. (cited at 62-63)