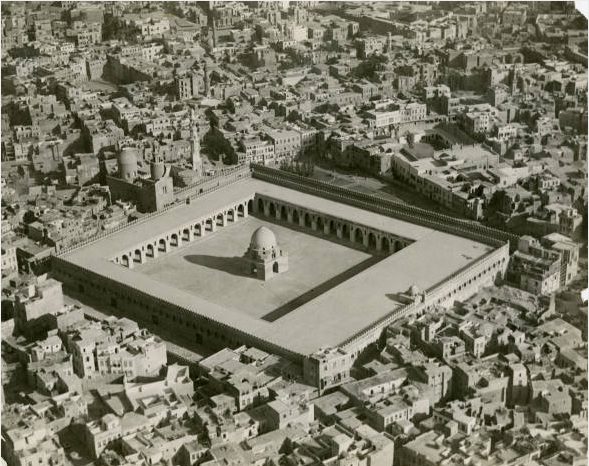

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

One of the ways that I like to write is simply to throw things rapidly into a computer file, as the thoughts occur to me, for later revisiting. At that point, I’ll clean them up, organize them into a suitable flow, check assertions, provide references where appropriate, smooth out inconsistencies, and otherwise make what I’ve written suitable (I hope) for publication.

I’ve already announced my intention to compile a small volume of brief introductions to books that I like, under the current working title of Ten Muslim Classics:

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/danpeterson/2019/07/ten-muslim-classics.html

I’ve decided, quite arbitrarily, to begin with the Thousand and One Nights, or the Arabian Nights. So, here, I continue to use this blog as my workshop for that project. It’s a good way of writing while up in and around the Canadian Rockies, far from my libraries.

These aren’t finished products by any means. They’re preliminary drafts, hasty sketches. A first step.

The textual history of the Thousand and One Nights is extraordinarily complex, for the simple reason that, as already mentioned, there is no single author behind the stories, and no single time or place where they can be said to have been complete. In his introduction to his own translation of the Nights, Husain Haddawy tells how he became acquainted with the stories as a child growing up in Baghdad, when old ladies visiting his grandmother would begin telling them orally, mixing and modifying them, condensing and expanding them, adding to them and streamlining them, on each occasion. And, as he himself says, many of the tales plainly had a long history of oral transmission (almost certainly precisely like the oral transmission that he himself experienced at first hand) before they were ever written down.

That is why I find it distinctly odd that Haddawy is so insistent that the fourteenth-century Bibliotheque Nationale Syrian manuscript edited and published by Professor Muhsin Mahdi of Harvard — whom, incidentally, I knew, and who was somewhat involved at the very launch of BYU’s Islamic Translation Series (whereby hangs a tale in itself that I may or may not ever publicly tell) — represents the definitive text of the Thousand and One Nights. I’m not even sure that I know what it would mean for something to be the “definitive text” of the Nights.

And that is why I remain unconvinced that the Bibliotheque Nationale manuscript’s omission of such famous stories as “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp,” “Sindbad the Sailor,” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” — popularly thought, I suspect, to be at the very heart of the Nights — means that these tales ought to be discarded and dismissed as not pertaining to the collection, proper. In fact, Haddawy has translated Sindbad and Other Tales from the Arabian Nights; he regards the Sindbad cycle of stories as genuinely very old but also as a “late addition” to the Nights.

That said, Haddawy’s 1990 translation of the Mahdi edition is the version that I have chosen to use in my course at Brigham Young University titled “Introduction to the Humanities of Islam.” It’s a good and accurate translation, as far as it goes. But I encourage my students to remember Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin, as well. (These being among the very most popular characters associated with the Nights, often appearing in popular culture, I think it unlikely that my students will never encounter them on their own. So I’m content to remind them of the frame story, and to introduce them to such lessser known figures as the porter and the three ladies of Baghdad, the hunchback, the fisherman and the genie, Nur al-Din Ali b. Bakkar, and so forth.)

Posted from Calgary, Alberta, Canada