“Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action,” in modern Persian.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

For my revised and expanded book on the Middle East for a Latter-day Saint audience:

The dominant religious tradition among the pre-Islamic Iranian peoples was Zoroastrianism. In the West, the tradition was named after its founder, the priest and prophet Zoroaster, whose name in Persian is Zartosht or Zardosht. (In Persian, it is called Mazdayasna, meaning “Mazda worship” or “Mazda devotion.”)

There is little agreement about Zoroaster’s birthplace — probably somewhere in the eastern part of what is today Iran, perhaps even in Afghanistan — and there is no consensus regarding the dates of Zoroaster’s life. It has been placed by various scholars at points ranging from 1700 BC to roughly 550 BC. But some information seems to be known about his life: Initially, for example, he set out to reform the pantheistic religion that was practiced in his community. When he was thirty years old, though, the supremacy of Ahura Mazda (“Lord Wisdom”) was revealed to him in a vision. All other “deities” were relegated to the status of demons or other supernatural creatures. Angra Mainyu (something like “Destructive Mind” or “Malign Spirit”), also known as Ahriman, was the evil opponent of Ahura Mazda in a dualistic opposition of good and evil, light and darkness.

Among the principal ethical principles of Zoroastrian teaching are these:

- Following the Threefold Path of Asha (“truth,” or “cosmic order”): Humata, Hukhta, Huvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds).

- Practicing charity as a way of maintaining the alignment of one’s soul with Asha and in order to spread happiness.

- Recognizing the spiritual equality and duty of men and women.

- Being good for the sake of goodness, without seeking reward.

The central scriptural texts of Zoroastrianism are gathered in a collection called the Avesta, which is written in an old Iranian dialect that is known, appropriately enough, as Avestan. Included in the Avesta are a number of hymns — the Gathas — that are ascribed to Zoroaster. However, as a whole the current version of the Avesta dates, at the oldest, from the era of the Sasanian Empire.

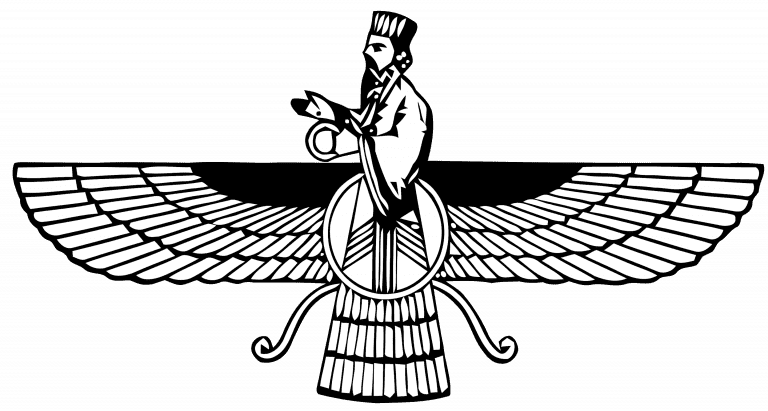

The Zoroastrian faith spread widely, first across the lands of the Iranians and then along the ancient trade routes into Central Asia and even into East Asia. It was the religion of the Seleucids, the Parthians, and the Sassanians. The so-called Faravahar, shown above, is one of the major symbols of the faith, although the symbol may well pre-date Zoroaster (depending on when one places his life) and although it has also become a secular symbol of Iranian ethnic and national pride.

Zoroastrianism survived into the twentieth century in certain isolated areas of Iran, but adherents of the religion have not always fared well under the Islamic Republic there. They are more free and more numerous in portions of India (particularly in and near Mumbai, formerly known as Bombay), where the Parsis or Parsees (“Persians”), as they are known, are mostly descendants of Iranian immigrants. (Zubin Mehta — music director emeritus of both the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor emeritus of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra — was born to a Parsi family in what was then called Bombay.)

Zoroaster shows up in a variety of surprising ways in Western culture. Here, I’ll mention just two threads: (1) In Mozart’s marvelous opera Die Zauberflöte (“The Magic Flute”), he appears as Sarastro, who, in the fantasy world of the opera, is evidently the high priest of an Egyptian temple of Isis and Osiris and the leader of a college of priests dedicated to justice and truth. (2) In his 1883 work Also Sprach Zarathustra (“Thus Spoke Zarathustra”), the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) created a “second” Zoroaster, using the ancient Iranian prophet’s name to voice his own thinking. In 1896, the German composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) composed an orchestral “tone poem” that was named after Nietzsche’s philosophical novel. Strauss’s work became especially famous after 1968, when Stanley Kubrick used its initial fanfare (“Einleitung, oder Sonnenaufgang,” or “Introduction, or Sunrise”) in his memorable film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In the third century, a new Iranian prophet arose by the name of Mani (AD 216-274/277). Mani had been raised in Babylon, in a family that belonged to a Jewish Christian sect. Probably also tinged with Gnosticism, its tenets seem to have included both the notion that apostles or prophets undergo a kind of reincarnation and a docetic view of Christ — i.e., that, as an impassible deity (i.e., a god who acts but is not acted upon), he only appeared (Greek δοκέω [dokeō], “to seem”) to have a physical body and, thus, only appeared to suffer in the Garden of Gethsemane and on the cross. At the age of twelve, though, and again at the age of twenty four, Mani experienced visions of a heavenly “twin” of his, a syzygos, that called him to depart from the sect in which he had been raised and, instead, to preach the true message of Jesusm a new gospel.

Mani’s doctrine was based, once again, on the venerable Iranian idea of a rigid dualism of good versus evil, locked in perpetual struggle, and it was intended to succeed and complete the teachings of Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism. Light and darkness, good and evil, were once entirely separate. But they have become commingled, and salvation consists not only in returning to the world of light but in helping all other “particles of light” to do so.

At the first, Manichaeism, as the religion founded by Mani has come to be called, won the support of many high-ranking political leaders. With the backing of the Sasanian Empire, therefore, Mani began to organize missionary efforts and to send out “apostles.” But he was opposed by many members of the Zoroastrian clergy and, eventually, he lost the support of the Sasanid elite. The historical chronicles seem to suggest that he died in prison under the Persian emperor Bahram I while he was awaiting execution.

Nevertheless, Manichaeism spread rapidly throughout the areas in which forms of Aramaic/Syriac were spoken. Its period of particular thriving occurred between the third and seventh centuries after Christ and, at its height, it ranked among the most widespread religions in the world. Manichaean scriptural texts and sanctuaries for worship can be found in China, for example, and the religion had reached Egypt by at least AD 244 and Rome by AD 280. Manichaean monasteries are known to have existed in Rome by AD 312. For a while, indeed, it was a serious rival to Christianity. The great St. Augustine of Hippo (AD 354-430), for instance, spent a number of years as a Christian convert to the teachings of Mani before returning to Christianity in AD 387 and becoming, thereafter, perhaps the single most influential Christian writer after the close of the New Testament. Intriguingly, some modern scholars have suggested that Manichaean ideas influenced the development of Augustine’s Christian thought on such topics as the nature of good and evil; the concept of Hell; the separation of humanity into elect, hearers, and sinners; his own plain hostility to the flesh and to sexual activity; and, very particularly, his doctrine of Original Sin. Not insignificantly, Augustine’s theology sometimes seems quite dualistic..

A much lesser-known offshoot of Zoroastrianism was founded in the early Sasanian period by a Zoroastrian mobad or priest who was a contemporary of Mani and whose name, as it happens, was Zardosht (Zoroaster). However, it is often called Mazdakism, taking its name from Mazdak, a powerful prophet and reformer who became a focus of controversy during the reign of the shah or emperor Kavad I (who ruled from 498 AD to 531 AD). Mazdakism has been identified by more than a few writers as an early form of socialism or even a proto-communism, because of its strong emphasis on a community of property and on sharing the benefits of work done by the community as a whole.