***

Happily, we were able to attend the funeral of our friend and Orem neighbor yesterday. (See “Farewell, For Now, to a Friend,” but also one of the “other matters” here.) Doing so, however, has definitely put me into an elegiac mood.

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day.

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away.

Change and decay in all around I see.

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

Those words, never before particularly important to me, came powerfully and continually to my mind in the days leading up to my father’s death, and, curiously, an instrumental version of that hymn was playing softly over the hospital sound system while we were sitting by my mother’s bedside as she drew her last breaths.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been acutely aware of the transience of things. When I see beautiful flower gardens — as we saw just the other day in front of the administration building at BYU — I almost immediately remember that “This will not last.” Visiting ancient ruins, I inevitably think of the people who once walked there, who were as vividly alive in their brief day as we are in ours. I see older films and realize that the actors playing the handsome, beautiful, and witty characters in them are now all dead. No matter how hard even the best and most dedicated athletes exercise, they’ll eventually wind up physically incapacitated (if they haven’t already died by then.) Visiting the now-public homes of the extremely wealthy — from Versailles to San Simeon, from the Villa Vizcaya in Miami and Neuschwanstein in Bavaria to Doris Duke’s “Shangri La” in Honolulu — I’m forcefully struck by the fact that those who once lived in them have been gone far longer than the brief span of their occupancy. Sic transit gloria mundi. Thus passes the glory of the world. However many years we labor to build a spectacular home for ourselves, we simply won’t stay there very long.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

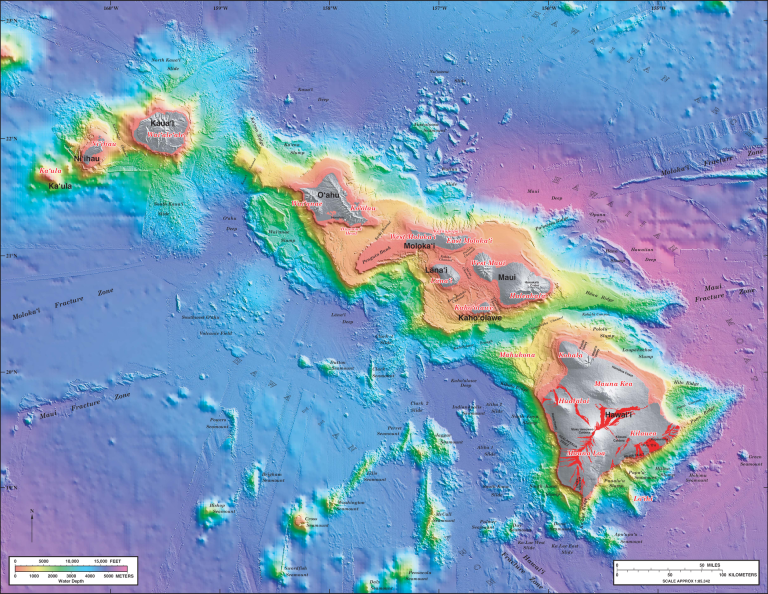

Curiously, no place on the earth makes me more aware of change and decay than does Hawaii. My parents first brought me here when I was five years old. I didn’t come again until I was a senior in high school, and then I was absent again for some time after that. Now, though, I’m genuinely not sure how many times I’ve been here — mostly for pleasure, but also for lectures and even for speaking to a devotional assembly at Brigham Young University’s campus at Laie, on the north shore of Oahu. Since my first visit to the islands as a very young child, they’ve moved approximately 14.5 feet to the northwest.

They’ve moved because the Pacific Plate, on which they sit, is moving. And it’s moving over a geological “hot spot.” A “hot spot” is an area under the earth’s rocky outer layer or crust where the magma is hotter than the surrounding magma. The magma plume that results causes the rocky crust to melt and to grow thin and, thus, to yield a place for the outbreak of volcanic activity. And that volcanic activity, in turn, is what has created the Hawaiian Islands. (And, of course, it’s what attracts me to visit the Hawaiian Islands, which represent one of the few places on the planet — Iceland, of course, would be another, and, naturally, it’s on my bucket list — that matches the perpetual seething rage that some of my anonymous critics claim to have detected in me.)

The movement of the Pacific Plate to the northwest makes volcanic action along the Hawaiian Ridge seem (to our vision, which experiences the crust as stable and unmoving) to move toward the southeast. Basically, therefore, the oldest islands in the Hawaiian Islands chain — Necker Island, for example, and Midway Atoll — are to the northwest. From Kure Atoll at the one end to the Big Island of Hawaii is an extent of roughly 1500 miles. Kaua’i is the oldest of the main Hawaiian islands. The Big Island is the newest, being the product of five distinct volcanos, and it is still volcanically active. Of its five originating volcanos, though, Kohala last erupted 60,000 years before the present and Mauna Kea last erupted 3,500 years ago; these two are generally considered dormant (which, by the way, does not mean extinct). Hualalai’s last eruption was in 1801, and that may be its final gasp. Or not. Only two of the Big Island’s volcanoes are active today — Mauna Loa and Kiluaea, both of which (surprise!) can be located roughly in the island’s southeast. Mauna Loa erupted in 1984; Kilauea is generally reckoned among the most active volcanoes on the planet. Moreover, about twenty-two miles off the southeastern coast of the Big Island is the Lōʻihi Seamount, an active volcano that is roughly 3200 feet beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean but that, in approximately 10,000 years, at current rates, will debut as the newest island in the Hawaiian chain. (I’m currently selling beachfront property on Lōʻihi. Contact me soon. It’s going fast.)

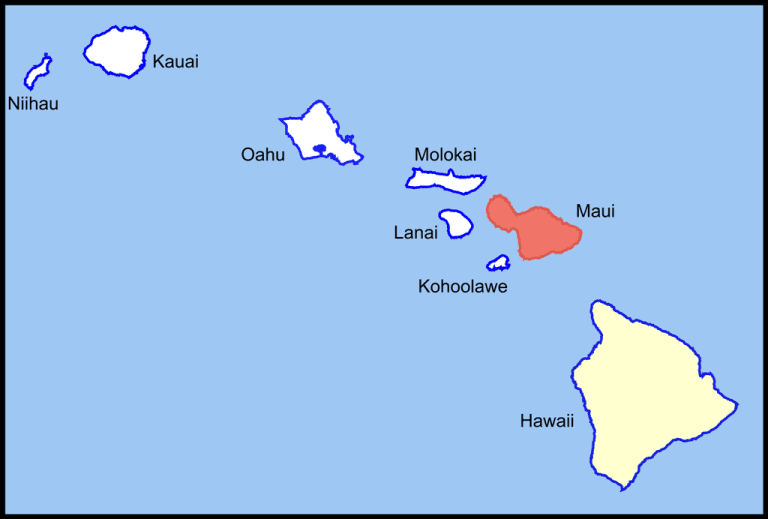

The island upon which I’m writing, Maui, has been called a “volcanic doublet,” having been formed from two distinct shield volcanoes that formed a low isthmus between them. Unsurprisingly, that low and relatively flat isthmus is where Kahului and Maui’s airport are located, and where Wailuku, the county seat — Maui is a separate Hawaiian country — is also to be found. Maui is actually just a portion of a considerably larger unit, Maui Nui (“Greater Maui”), that also includes the islands of Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Molokaʻi, and the so-called Penguin Bank, which is now submerged beneath the ocean. During periods when the level of the sea has been lower, perhaps as recently as 20,000 years ago, these can all be joined together as a single island.

It should hardly be surprising now to learn that the western part of the island is the oldest part of it, and that the westernmost of the two principal volcanos has been pretty quiet and is much eroded. The famous volcano to the east, however, Haleakalā, is considerably higher (rising somewhat more than 10,000 feet above the surface of the sea), much larger, and, although dormant, is still capable of eruptng. (Its last eruption was in 1790.)

It appears now, however, that Maui’s period of growth is over. Gradually, the ocean that I can see right now and the waves that I can sometimes hear above the bird songs are wearing it down. Eventually, it will become a coral atoll, and then it will disappear beyond the waves. The Kaanapali resorts that were scarcely a developer’s dream when I spent an entire day walking the beach north of Lahaina back in 1970 will be renting out only their top floors, and at enormous discounts. And then you’ll all realize that my strong sense of the ephemeral character of everything around us wasn’t misplaced, after all. The famous and recurrent description of the weekly Tabernacle Choir broadcast as coming “from within the shadows of the everlasting hills” is, in the end, poetic but not literally true. The “everlasting hills” aren’t everlasting. Not really.

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day.

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away.

Change and decay in all around I see.

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

Posted from Kāʻanapali, Maui, Hawaiʻi