***

With several friends, we spent a substantial part of yesterday visiting the former Nazi concentration camp of Dachau, which is located in what is now pretty much a pleasant suburb of Munich. Fifty-two years ago, I was scheduled to visit Dachau with a group of recent high school graduates during my first visit to Europe. Our tour guide, though, was a neo-Nazi — not at all the stereotypical skinhead thug that I would have expected; he was the son of an SS officer, yes, but he was also a charming young fellow, completely fluent in English and a student in what is now known as the Technische Universität Wien (the highly ranked Vienna Technical University) — and he really, really didn’t want us to go, because, he said, the Holocaust was an anti-German myth. We still wanted to go, however, so he finally made us an offer that, in the end, we just couldn’t refuse: He came up with tickets for our whole group to the Oberammergau Passion Play, for the same day as our scheduled excursion to Dachau. Roughly sixth row back, center. (I wonder what back channel Nazi-sympathizer connections he used to make that happen.) I remember reasoning that Dachau would always be there, but that the Passion Play was performed only every ten years. So, with my fellow tourists, I chose Oberammergau. As it turned out, I’ve now attended three seasons at Oberammergau and will shortly attend my fourth. But, until yesterday, I had never made it to Dachau.

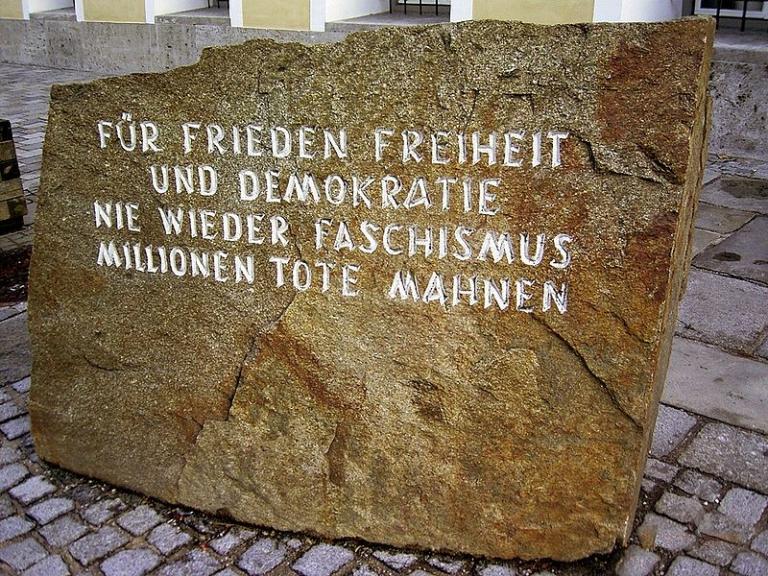

I’ve now been to three of the former Nazi labor camps — Mauthausen (which I’ll be visiting again tomorrow) and Buchenwald and Dachau — which I have done, to a significant degree but not solely, out of a sense of moral obligation. Such places and such things simply must not be forgotten.

Thereafter, my wife and I accompanied three new arrivals for our tour to the Marienplatz, the Petruskirche, and the Viktualienmarkt back in Munich.

Our tour formally began today. Our group took a combined bus-and-walking tour of greater Munich, including the remarkable Allianz Arena where FC Bayern München plays (which is encased entirely in plastic that can change colors at night) and the spectacular BMW Welt. We drove past the Feldhernhalle — which we and our friends had already walked past a couple of times before I realized that it’s the site where the famous 1923 Beer Hall Putsch that was led by Adolf Hitler and General Erich Ludendorff (inaccurately but not altogether unjustly portrayed as a crazed villain in the 2017 film Wonder Woman) came to its unsuccessful end. And we walked them around the Marienplatz, the Petruskirche, the Viktualienmarkt, and the famed Hofbräuhaus, which, I’ve now figured out, was the scene of one of Hitler’s very last public speeches. On that occasion, he addressed the alte Kämpfer, the “old warriors” who were among the earliest members of the Nationalsozialisten.

We had a good Bavarian lunch at a restaurant near the Hauptbahnhof, the main Munich train station, and then spent two hours or so at the magnificent Nymphenburg Palace, the summer residence of the Bavarian royal family, and on its vast grounds.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

Thereafter, we drove away from Munich toward the Bavarian Alps. I must honestly say that, as the Alps began to appear ahead of us, and as we began to drive among the meadows and the woods of the Alpine landscape, I was surprised at the emotional impact that seeing them had on me. I had found Munich interesting, but it’s this green and mountainous Alpine scenery that really moves me, much more than I know how to express. I had almost forgotten: This is the kind of landscape that I find most powerfully moving. It has really affected me, still tonight.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Our group had a good dinner of soup and Wienerschnitzel and panna cotta with raspberries in a nice restaurant here in the pretty town of Ruhpolding, where we’re now going to be staying for a while. My wife and I went out after dinner for a pleasant walk under occasional rain sprinkles to visit with some sheep and to stand on a bridge looking down at a rapidly moving stream. Glorious.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

I bought three books yesterday in the shop at KZ-Dachau (how very remarkable, in a sense, that KZ-Dachau even has a shop!):

- Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Die 101 wichtigsten Fragen [“Hitler: The 101 Most Important Questions”] (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2019)

- Inge Scholl, Die Weiße Rose (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 1993). An account of the famous non-violent anti-Nazi resistance group “The White Rose,” which was led by five students and a professor at the University of Munich — including the author’s devoutly Christian siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl, who were executed by guillotine just four days after their arrest, on 18 February 1943.

- Harald Welzer, Täter: Wie aus ganz normalen Menschen Massenmörder werden [“Perpetrators: How Mass Murderers Emerge from Completely Normal People”] (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 2005). This, I think, is perhaps the most important and urgent question posed by the Third Reich.

In the third book, the author cites a 1946 passage from the Swiss playwright and novelist Max Frisch that I will share here in my own rough translation:

When people who have enjoyed the same upbringing that I did, who speak the same words that I do and love the same books and the same music and the same paintings that I do — when these people are in no way protected from the possibility of becoming monsters and of doing things that we never would have believed possible for people of our time except in uniquely pathological cases, on what basis can I be confident that I myself am protected from such things? (7)

Posted from Ruhpolding, Upper Bavaria, Germany