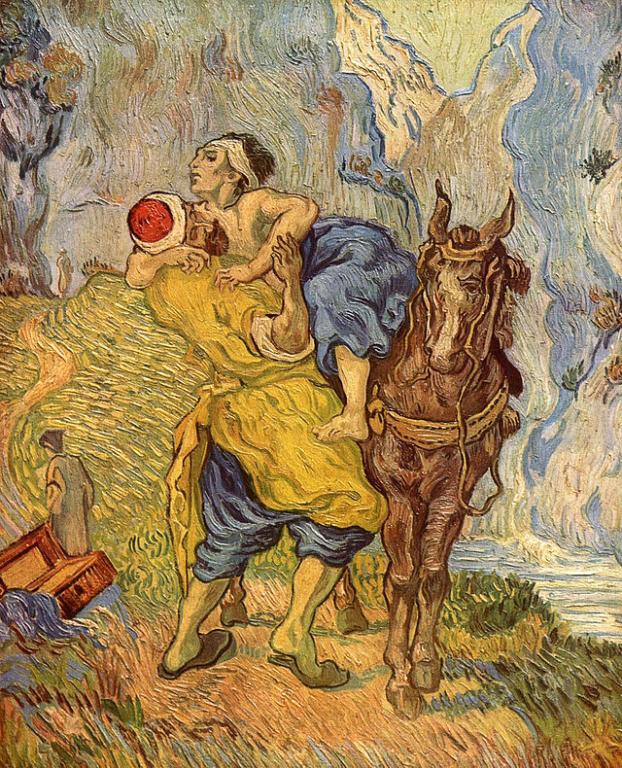

PA, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

***

I recently recorded an episode with “Richie T” of The Cultural Hall Podcast regarding, among some other things, the new Undaunted film, but I think that I failed to mention when it went up online. (I’ve been occupied of late, and out of sync, time-wise, with things originating in North America.) However, some folks — there’s always somebody out there, right? — might find it enjoyable or at least palatable:

“Undaunted: Witnesses of the Book of Mormon Ep. 602 The Cultural Hall”

I’m also not absolutely sure that I ever called attention here to this article that I published in Meridian Magazine not too terribly long ago. Maybe I did. Maybe I didn’t:

“Getting Closer to the Original Text of the Book of Mormon”

***

You might enjoy this little profile:

***

We spent the day today in Bilbao, a very attractive city in the Basque region of northwest of Spain. We saw it from a scenic overlook, walked around its oldest section, and spent a couple of hours in its spectacular and justly famous Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Gehry. Our guide today, for both the city and the museum itself, was superb, and he was very knowledgeable and informative about art history. I can’t express, though, how disappointed I was to discover that Frank Gehry is Jewish. (His birth name was Frank Owen Goldberg, and the name given to him by his grandfather at his bar mitzvah was Ephraim.) Why would I be disappointed? Because the Jewish contribution to the sciences and literature and so forth was already vastly out of proportion to the number of Jews in the world. And now I learn — why I wasn’t already aware of it, I don’t know — that Frank Gehry, whose (adopted!) name gave me no clue — is Jewish, too! Our Jewish brothers and sisters have so much talent, and have made such remarkable contributions. Is there anything left over for us poor, pathetic goyim?

During our tour today, we were shown the downtown Teatro Arriaga and were told very briefly about the man for whom it was named. He was Juan Crisóstomo Jacobo Antonio Arriaga y Balzola or, in short, Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga. Sadly, I had never heard of him before. But I’ve now learned a bit about his story:

Arriaga was born on 27 January 1806 near Bilbao. He was a child prodigy as a violinist but also a remarkably precocious composer, which apparently led some to dub him “the Spanish Mozart” — despite the fact that, ethnically, he was actually a Basque. (Coincidentally, he shared his birthday with Mozart, who was born on 27 January 1756, precisely fifty years earlier to the day, and, mutatis mutandis, he and Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart shared their first two names.) And, in fact, from what I’ve read about him just today, Arriaga’s compositions — which are said to be inventive, fresh, and technically resourceful — place him somewhere between the Classical tradition of Haydn and Mozart, on the one hand, and, on the other, the Romanticism of Rossini and Schubert. Arriaga had an opera performed at Bilbao already in 1820, when he was about fourteen or fifteen years old. It was titled Los ésclavos felices (“The Happy Slaves”), but it is now lost. At some point, he also composed three string quartets and a symphony.

Arriaga enrolled in the Conservatoire de Paris, where he studied under, among others, Luigi Cherubini. All of his teachers were apparently impressed by his use of sophisticated harmonies, counterpoint, and fugue, despite the fact that he had received minimal or even no formal instruction in such matters. In fact, Cherubini referred to Arriaga’s now-lost fugue for eight voices, based on the Credo . . . et vitam venturi, as “a masterpiece.”

Incredibly, by the age of eighteen Arriaga was himself an assistant professor at the Conservatoire de Paris. He was intensely dedicated to his work there, and to music, and this may have taken a toll on his health. He contracted a lung ailment (possibly tuberculosis), and that, coupled apparently with extreme fatigue and exhaustion, killed him. He died in Paris on 17 January 1826, just ten days before his twentieth birthday, and he was buried in an unmarked grave at the Cimetière du Nord in Montmartre.

The Wikipedia article on Arriaga quotes Barbara Rosen, author of his only English language biography, Arriaga, the Forgotten Genius: the Short Life of a Basque Composer: “It is . . . possible to hear passages in Arriaga’s work similar to Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Rossini, although he sometimes fails to achieve the complexity of these composers’ more mature works. Nevertheless, Arriaga has an identifiable and original style which, in time, undoubtedly would have become more individual and more recognizably his own, possibly incorporating more Spanish and Basque than Viennese elements.”

Stories like Arriaga’s affect me powerfully. I’m painfully aware of lives cut short, or talents undeveloped, or promise unfulfilled. One such case, obviously, is Mozart himself (1756-1791), who died at the age of thirty-five. Another is the great Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), who passed away at only thirty-eight. And, of course, there is the astonishing Indian mathematical prodigy Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), about whom I’ve written here in ““The Man Who Knew Infinity” (Part One)” and ““The Man Who Knew Infinity” (Part Two).” I explicitly addressed the topic of truncated lives, and of capacities that were never allowed to mature, in an article that I wrote for the Deseret News about Ludwig van Beethoven.

In a letter, Mendelssohn once described death as a place “where it is to be hoped there is still music, but no more sorrow or partings.” (See Peter Mercer-Taylor, The Life of Mendelssohn [New York and Cambridge: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000], 206.) And precisely that is what I believe. Right down to the music, which is abundantly attested in innumerable accounts of near-death experiences.

I absolutely love this quotation from President Russell M. Nelson:

“We were born to die and we die to live. As seedlings of God, we barely blossom on earth; we fully flower in heaven.”

Posted from the Bay of Biscay, between Bilbao, Spain, and Bordeaux, France