This presentation, which was delivered by Camille Stilson Williams on Saturday, 12 March 2016, at 2016’s Second Interpreter Science & Mormonism Symposium: “Body, Brain, Mind, and Spirit,” has just gone up on the website of the Interpreter Foundation: “Conference Talks: Veiled in Flesh: An LDS Perspective on the Body”

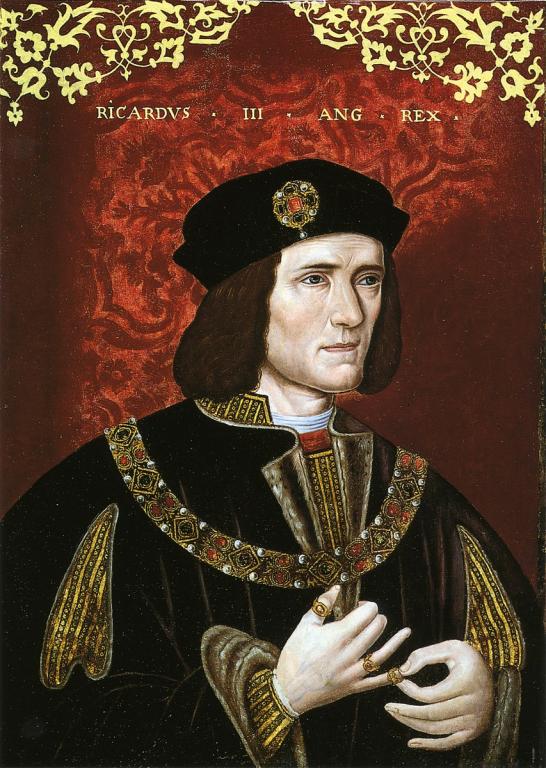

I was very quickly aware of the news when, remarkably, the skeletal remains of King Richard III of England were found under a “car park” — in Americanese, a “parking lot” — in the heart of the English city of Leicester in September 2012. Thanks most prominently to his depiction by William Shakespeare in the play Richard III, King Richard (1452-1485) has long been regarded as one of the consummate fiends of English or even world history. And I have a particular personal reason for being especially interested in him (even beyond our shared wickedness): I’ve very recently noted here — see “Tales of the Gloucester Crypt” — that

One of the most spectacular pieces of acting that I’ve ever seen was Gary Armagnac’s depiction of Richard III at the 1994 Utah Shakespeare Festival. For sheer brilliant evil, I’ve never seen the like. . . . It is etched unforgettably in my memory.

But I didn’t know The Rest of the Story. Happily, a reader who posts comments on this blog as “David Sanders” called my attention to a 2022 film called The Lost King that tells something of the story of Philippa Langley, who was the moving force behind the finding of Richard’s burial place. You can watch the trailer for The Lost King here.)

Since then, I’ve both watched the film and read the book The Lost King: The Search for Richard III that served, more or less, as its basis. The story is a fascinating one.

Philippa Langley is neither an academic nor an archaeologist nor a trained historian. But, for particular reasons (related rather differently in the book and in the film), she developed a fascination — arguably, a driven obsession — with the last of the Plantagenet kings of England, the last English king to die in battle, and that fascination compelled her to try to locate his resting place and to afford him an honorable burial commensurate with his rank as an “anointed king.” It has also led her to attempt to correct his extraordinarily negative reputation, an effort in which she and other revisionists have, I think, at least partially succeeded. Certainly in my case. Shakespeare’s play remains a literary masterpiece, but it is also a masterpiece of Tudor-era propaganda, of which the Bard was not only a consummate purveyor but also, very likely, a sincerely misled victim.

Anyway, what is it about this story that particularly fascinates me? It’s the unmistakable suggestion of something beyond the normal in the discovery of Richard’s earthly remains. (Please note that, importantly, the book contains not a single reference to any apparition of Richard like that repeatedly shown in the movie. The book’s claim is much more modest and less seemingly nuts than that. I assume that the apparition is intended merely to illustrate, cinematically, Philippa Langley’s fixation on Richard.)

For various reasons explained, I think, in both movie and book, research had concluded that Richard had probably been interred within the medieval Greyfriars Church in Leicester, the specific site of which had been lost for many generations. Some contended that at least part of it might be located beneath one or more downtown carparks. Or, if searchers’ luck proved bad, it would be under one or more multi-story buildings in the vicinity. But it was a very large area to search:

Local resident Audrey Strange had highlighted the size of the known Greyfriars precinct in Leicester. Stretching from Hotel Street in the east to Southgate Street in the west, and bordered by Friar Lane at the south and St Martin’s and Peacock Lane in the north, it covered some seven acres, or the equivalent of five football fields. It was a sobering thought. Finding the small friary church in such an immense search area would be challenging enough; finding a particular grave even more so.

Nonetheless, Philippa traveled from her home in Edinburgh to Leicester to see the area for herself. Visiting one of the carparks, she felt nothing at all. Maybe the grave was there. Maybe not. There was, at the moment, no way of telling. But then she located another parking area on her city map that she had overlooked and passed by. Should she look at it?

I was going to move on but experienced an overwhelming urge to enter. I slid around the barrier and into the car park which, again, was pretty much deserted apart from a few scattered vehicles. It was a large open space for seventy or more vehicles, surrounded by Georgian buildings with a large red-brick Victorian wall running north to south straight ahead of me. I found myself drawn to this wall and, as I walked towards it, I was aware of a strange sensation. My heart was pounding and my mouth was dry — it was a feeling of raw excitement tinged with fear. As I got near the wall, I had to stop, I felt so odd. I had goose-bumps, so much so that even in the sunshine I felt cold to my bones. And I knew in my innermost being that Richard’s body lay here. Moreover I was certain that I was standing right on top of his grave. Back home and trying to comprehend what I had experienced, friends and family told me not to dismiss it. A year later, after completing the first draft of my screenplay, I returned to the car park, questioning if what I had felt that day had been real. As I walked to the same spot and looked at the Victorian wall, the goose-bumps reappeared. I stared down at my feet. Slightly to my left, on the tarmac, there was something new — a white, hand-painted letter ‘R’, denoting a ‘reserved’ parking spot, but it told me all I needed to know.

As I told him about the GPR survey I planned to commission to attempt to reveal its walls beneath the tarmac, we walked on to the same spot where I had my intuitive feeling, and I experienced the same powerful reaction once again.

The machine will very shortly be going right over the painted letter ‘R’, close to where my instinct told me Richard’s remains lay when I first came here. I still believe it. Nothing has changed my mind. . . .I realize that Morris’s head, poking out at me from the trench, is only a few feet from where the letter ‘R’ once existed and right where I had my intuition. My heart is pounding. I feel odd, as if I’m somehow here but not here. My legs are moving, taking me to the edge of the trench. I’m jumping in, getting to Morris as fast as I can. . . .The odd sensation I’m experiencing won’t go away. All I can think is that it’s Richard. I hear myself telling Morris that we’re right beside the ‘R’ that marked the spot. . . .It is abruptly quiet and a profound feeling of complete peace washes over me. And I know then in the deepest part of me that if this is Richard he wanted to be found — was ready to be found. All at once I remember what day it is: 25 August, the anniversary of Richard’s burial in the Greyfriars, the day he was laid to rest. In the days, months and years to come it might also become known as the day he was found again. . . .Neither of us can rationally explain the discovery of remains where my instinct told me they would be; that they really may be what we have been searching for.

And what of the intuitive feeling in the car park that had acted as the catalyst and impetus for the search for Richard? Had this ever happened before? Many of our great discoveries began with intuition, an idea, a leap of faith. In 1937, Edith Pretty had a similar feeling about a large earth mound on her land in Suffolk, which led to the discovery of Sutton Hoo. This was a complete Anglo-Saxon long ship burial, believed to be of the seventh-century King Rædwald and was described as one of our greatest archaeological discoveries.

Remarkable. Is it mere coincidence? Or is it a case of what some call “extraordinary knowing”? There seems little question about how Philippa Langley views it.

Finally, a warning: This year, for the very first time, I will not be the concluding speaker at the annual FAIR conference. Instead, I will be the opening speaker, on Wednesday morning, when, all through the house, not a creature is stirring, not even a mouse, the children are nestled all snug in their beds, and mamma in her ‘kerchief, and pa in his cap, are still settled down for a long summer’s nap. So, if you plan to attend the conference or to participate in it online, that is the crucial time — and an easy time — to avoid. After all, if anybody can give Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III real competition for sheer unrelenting evil, it’s probably yours truly. Good luck!