Wikimedia Commons public domain image

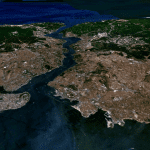

First thing this morning, we visited the hilltop ruins of the ancient Greeek city of Assos ( Ἄσσος), which are located near today’s Behramkale or Behram on the Aegean coast in the province of Çanakkale. It is on the southern side of the Biga Peninsula, which isbetter known by its ancient name of “the Troad.” Specifically, Assos sits on the coast of the Adramyttian Gulf (in Turkish, the Edremit Körfezi)

During the period of the town’s greatest flourishing, Hermias of Atarneus, a student of Plato, ruled not only Assos and the Troad but the island of Lesbos. Consistent with his educational background, Hermias encouraged scholars and philosophers to move to the city. One of those who accepted his invitation was Aristotle, who arrived in 348 BC and, in fact, married Hermias’s niece, Pythia. Aristotle founded an Academy in Assos where he became chief amongst a group of philosophers and, with them, began a program of zoological and biological research. Unfortunate, those good things came to an end a few years later when the Persians invaded and tortured Hermias to death. Aristotle fled to Macedonia, which was ruled by his friend King Philipp II of Macedon, the father of the future Alexander the Great. In Macedonia, Aristotle became the tutor to Alexander. A modern statue of Aristotle stands at the entrance to Assos.

The New Testament book of Acts mentions visits to the city by both its narrator, Luke the Evangelist, and the Apostle Paul:

And we went before to ship, and sailed unto Assos, there intending to take in Paul: for so had he appointed, minding himself to go afoot. And when he met with us at Assos, we took him in, and came to Mitylene. (Acts 20:13-14)

After leaving Assos, we visited Alexandria Troas, which served as the starting point for the Apostle Paul when he set sail to Europe during his second missionary journey (ca. 50-52 AD). Paul had received a vision calling him to Macedonia:

And they passing by Mysia came down to Troas. And a vision appeared to Paul in the night; There stood a man of Macedonia, and prayed him, saying, Come over into Macedonia, and help us. And after he had seen the vision, immediately we endeavoured to go into Macedonia, assuredly gathering that the Lord had called us for to preach the gospel unto them. Therefore loosing from Troas, we came with a straight course to Samothracia, and the next day to Neapolis. (Acts 16:8-11)

He also visited the city during his third missionary journey (ca. 53-58 AD). And, later, he spent a week in Troas preaching – apparently at considerable length:

And we sailed away from Philippi after the days of unleavened bread, and came unto them to Troas in five days; where we abode seven days. And upon the first day of the week, when the disciples came together to break bread, Paul preached unto them, ready to depart on the morrow; and continued his speech until midnight. And there were many lights in the upper chamber, where they were gathered together. And there sat in a window a certain young man named Eutychus, being fallen into a deep sleep: and as Paul was long preaching, he sunk down with sleep, and fell down from the third loft, and was taken up dead. And Paul went down, and fell on him, and embracing him said, Trouble not yourselves; for his life is in him. When he therefore was come up again, and had broken bread, and eaten, and talked a long while, even till break of day, so he departed. And they brought the young man alive, and were not a little comforted. (Acts 20:6-12)

By the way, Eutychus means “Lucky.”

I’ve told the story here before, I think, but I’ll repeat it now: I served for very nearly ten years on what was then called the “Gospel Doctrine Writing Committee.” It was chaired by the remarkable Richard O. Cowan, of the BYU Department of Church History and Doctrine, and included such people as Kent Jackson and Ann Madsen of Ancient Scripture, Mae Blanch of English, and Clark Johnson of Church History and Doctrine. We produced the adult Sunday School curriculum for the Church at that time.

Our procedure was for each of us to receive an assignment for a particular set of scriptural passages. We would then work at home on producing a lesson on those passages in the prescribed format,. When finished, we would send our lessons to the other members of the committee for their critique. And, roughly twice each month, we would meet early on Sunday mornings for breakfast and for going through the lessons and the critiques, one after another. We would then return home, modify our lessons in the light of comments and critiques, and resubmit them. From that point, they would go up the Church ladder for possible further modification and eventual publication.

During one particular period, I was assigned a number of chapters from the book of Acts, including Acts 20.

It was our occasional practice to insert jokes into our draft lessons (e.g., about “ancient American airfields” and the like) for the amusement of other members of the committee. At this particular time, the format in which we were asked to write permitted only bulleted questions and bundles of questions, preferably with practical “life application.”

So, when I read through my assigned chapters, I naturally thought of the following practical questions:

- Have a class member read Acts 20:6-12. Have you ever killed anyone with a sacrament meeting talk? How did it make you feel? What steps can you take in the future to avoid such problems?

As I had hoped, the committee laughed. To my amazement, though, nobody took the questions out. I can only imagine that each successive reader thought that the next reader would chuckle and that he would then remove them. So, when the pre-publication galleys came back, that cluster of questions was still there. It had even passed the Correlation Committee. For a few seconds, I faced a staggering moral crisis: I thought that it would be hilarious to see those questions in German, Spanish, Portuguese, Afrikaans, Japanese, and Tagalog. In the end, though, I called Church headquarters and suggested that they might want to cut them out. The reaction on the other end of the line was stunned gratitude. I thought fleetingly about requesting a finder’s fee, but decided against doing so.

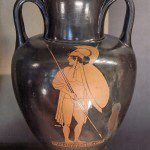

Our next stop after Alexandria Troas was ancient, quasi-legendary Troy, made imperishably famous in Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. For many generations, people had assumed that Homer’s account of the Trojan War was fiction and that Troy never existed — until the 1860s, when its ruins were found by the rich and eccentric genius Heinrich Schliemann.

The poems of Homer and those influenced by him were fundamentally important to ancient Greece, the Greeks’ closest equivalent to the Hebrew Bible, the foundation upon which all succeeding classical civilization rested. Even today, we remember Achilles, the Cyclops, Hector, Paris, Helen, Odysseus or Ulysses, the Land of the Lotus Eaters, Odysseus’s visit to Hades, the Sirens, the island of Circe, the Trojan horse, the suitors of Penelope. Omero poeta sovrano, Dante Alighieri called him (in his 1321 Divina Commedia, Inferno, Canto IV, line 88): “Homer, the sovereign poet.”

Somewhere along the Ionian coast opposite Crete and the islands was a town of some sort, probably of the sort that we should call a village or hamlet with a wall. It was called Ilion but it came to be called Troy, and the name will never perish from the earth. A poet who may have been a beggar and a ballad-monger, who may have been unable to read and write, and was described by tradition as blind, composed a poem about the Greeks going to war with this town to recover the most beautiful woman in the world. That the most beautiful woman in the world lived in that one little town sounds like a legend; that the most beautiful poem in the world was written by somebody who knew of nothing larger than such little towns is a historical fact. G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (1925)

We spent a fair amount of time walking around and through the ruins of the multiple levels of ancient Troy – the site is vastly improved for visitors since we were last here — and then we drove on to spend the night in Bursa, the original capital of the Ottoman Empire.

While walking through Troy, a member of our group who was trained at Caltech in both physics (undergraduate) and computer science (doctorate) told me a classic Caltech-style joke that I found very funny: Have you, he asked, heard of the unit of measurement called a millihelen? No, I replied. It’s the amount of power required to launch just one ship.

Posted from Bursa, Türkiye