(NASA public domain photograph)

Today, we left Bursa and drove to İznik, which may not sound familiar to many but which was an important city in early Christian history. İznik was known in ancient times as Nicaea – or, more accurately, as Νίκαια (Nikaia). It was the site of the First and Second Councils of Nicaea—respectively, the first and the last of the seven ecumenical councils of the Christian church—during the first of which the Nicene Creed originated. It was also the capital city of the Empire of Nicaea following the seizure of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin Catholics during the regrettable Fourth Crusade, and it remained such until the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantines in 1261. Nicaea also served as the capital of the Ottomans from 1331 to 1335.

The ancient city is surrounded on all sides by five kilometres (roughly three miles) of walls that are about ten meters (thirty-three feet) high. In their turn, the walls are surrounded by a double ditch on the land portions, and there were once also more than a hundred towers in various locations. Large gates on the three landbound sides of the walls afforded the only entrances to the city but, today, the walls have been pierced in many places for roads. Still, much of the defensive wall survives.

Our attention in İznik today, though, was focused on the Lesser Church of Hagia Sophia, which was the site of the Second Council of Nicaea in AD 787. This council was convened by the emperor of the Byzantines, Constantine VI, as well as by Empress Irene, and was attended by Pope Hadrian I. The so-called iconoclastic controversy had been roiling the Empire. Perhaps as a result of criticism from adherents of the still new and very aniconic religion of Islam, the question began to be debated whether the veneration of icons was legitimate or whether it constituted mere rank idolatry. The Second Council of Nicaea recognized the veneration of Christian images of Jesus and the saints as legitimate. (Ironically, the church was transformed into a mosque by conquering Muslim Turks in the 1300s, and it has long since been stripped of all images.) The council also forbade the appointment of bishops by secular government authorities, thus solidifying the independent authority of the church against that of the state.

But what about the First Council of Nicaea? As the source of the famous Nicene Creed, isn’t it vastly more important for Christians generally and for Latter-day Saints in particular than the Second Council? Yes, it is. And I spoke to the group while we drove on the bus about the First Council and went through the text of its creed with them. But we didn’t visit the place where that council was convened, because it is currently underwater and because (we’ve been there before) there really isn’t much to see there, anyhow.

Christianity had become a legal religion of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine I (Constantine the Great) by virtue of the Edict of Milan that he issued in AD 313. Constantine patronized Christianity, supporting it by granting privileges to the Church and its clergy, and he ultimately became the first Roman emperor to adopt the religion as his personal faith. However, although he certainly furthered the process by which the majority of the population became Christians and by which, some decades after his death, Christianity actually became the official religion of the State, he himself did not accept baptism until very shortly before he died in AD 337, in Nicomedia.

One of Constantine’s reasons for favoring Christianity was undoubtedly his hope that it would provide a kind of ideological clue that would assist him in unifying the Empire, which had been informally divided by language and cultural differences and even formally divided, politically. To his shock, though, Christianity itself was now riven by doctrinal disputes. Which is why he summoned the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325. (He would not establish his capital at Constantinople until AD 330.)

The Nicene Creed (Greek Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας, Sýmbolon tês Nikaías; Latin: Symbolum Nicaenum; lit. ’Symbol of Nicaea’) was adopted by the assembled delegates at Nicaea. I have published a few of my reflections on its text in an article written for Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship.

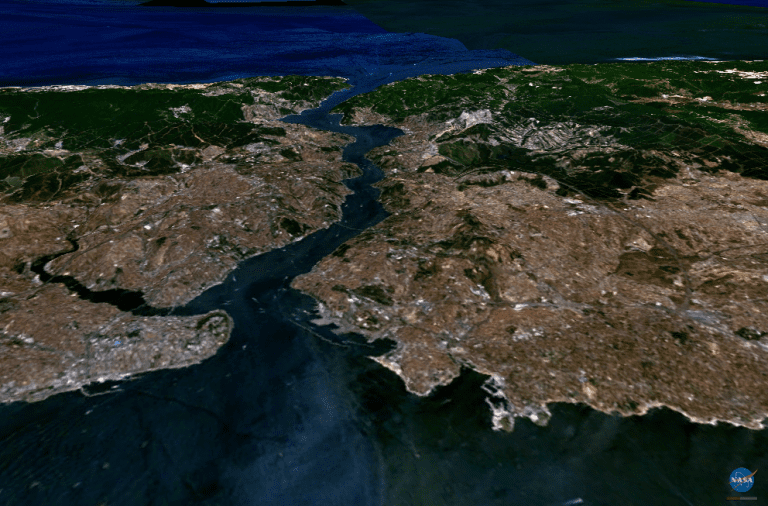

After visiting Nicea, we returned to Istanbul and did a cruise on the Bosporus (or Bosphorus). Such a cruise provides the best view of many of Istanbul’s most important features, including the Dolmabahçe Palace, the more modern, European-style palace that replaced the Topkapı Sarayı in the nineteenth century (and that some of us visited on the first day after our arrival here on this trip). If we had gone a bit further north (as our previous Bosporus cruises have done), it would also have provided an excellent view of the Rumeli Fortress.

Rumelihisarı (also known as the Rumelian Fortress and Roumeli Hissar Fortress) or Boğazkesen Fortress (literally “strait-cutter fortress”) is a medieval Ottoman fortification located on a series of hills on the European bank of the Bosporus.

The complex, which was conceived and built between 1451 and 1452 CE on the orders of Sultan Mehmet II, was commissioned in preparation for his planned Ottoman siege of the then-Byzantine city of Constantinople. His intent was to cut off any maritime military or logistical relief that might potentially have come to the Byzantines’ aid by way of the Bosporus Strait. (Hence the fortress’s alternative name, Boğazkesen, i.e. “Strait-Cutter” Castle. Its older sister structure, Anadoluhisari (“Anatolian Fortress”), stands on the opposite bank of the Bosporus, and the two fortresses functioned together during the final siege to cut off all naval traffic along the Bosporus, thus helping the Ottomans conquer Constantinople in 1453 and turn it into their new imperial capital of Istanbul.

The exact cause and date of the formation of the Bosporus apparently remain a subject of debate among geologists. One recent idea, which has been termed the Black Sea deluge hypothesis, was proposed in 1997 by two scientists from Columbia University. It suggests that the Bosporus was flooded around 5600 BC (or, according to a 2003 revision of the hypothesis, about 6800 BC) when the rising waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Sea of Marmara broke through to the Black Sea, which at the time, according to the hypothesis, was a low-lying body of fresh water. (Some have even suggested that the flooding of the valley of today’s Black Sea gave rise to the legends of catastrophic flooding, including the story of Noah’s flood, that are common across the area.) Many geologists, however, continue to believe that the strait is much older than that, albeit still relatively young in geological terms.

In the evening, our group said its formal farewell to Türkiye and İstanbul by eating its last supper together on the terrace of the Arcadia Blue Hotel. My wife and I have eaten at the Arcadia Blue on several occasions, and once even stayed in the hotel itself. Its dining room has a breathtaking view, looking out over the Hagia Sophia, the Sultanahmet or Blue Mosque, the Hippodrome, and, in the distance, the Topkapı Sarayı, and the Bosporus. I don’t think that there is a better view in the city, and I doubt that there are many views of any cityscape on the planet that can rival it. And yes, by the way, the food there is very good, too.

Posted from Istanbul, Türkiye