(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

The church of Smyrna (Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or Σμύρνα, Smýrna) was also one of the seven churches of Asia that are mentioned in the Revelation of John. (See Revelation 2.) Since around 1930 (in the wake of the founding of the Republic of Turkey), Smyrna has been known as Izmir. It’s where we spent last night.

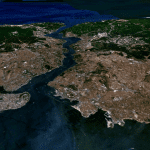

It is a port city that is located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Türkiye or Anatolia. Smyrna was situated at the mouth of a small river called Hermus and at the head of a deep arm of the sea (Smyrnaeus Sinus, today’s Gulf of Izmir) that reached far inland. This enabled Greek trading ships to sail into the heart of Lydia and, thus, made the city an important part of a vital trade route running between central Anatolia and the Aegean.

The Meles River, which flowed by Smyrna, was famous in classical literature and was even worshipped by those living in the valley. Moreover, a common and consistent tradition connects the great poet Homer with the valley of Smyrna and the banks of the Meles. The epithet Melesigenes (roughly, “born of the Meles”) was applied to him; the cave where he is said to have composed his poems was historically pointed out to visitors near the source of the river; his temple, the Homereum, stood on its banks.

A Christian church and, indeed, a bishopric existed in Pergamon from very early times, probably because of the city’s significant ancient Jewish minority. Its most important early Christian figure was its onetime bishop, St. Polycarp, whose name means something like “much fruit” and who was martyred at the enthusiastic urging of a combined mob of Jews and pagans in or around AD 153. Polycarp is said to have been a disciple of the apostle John and to have been ordained a bishop under John’s hand. Some scholars even believe that the New Testament epistles of 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus were actually written by St. Polycarp rather than by the apostle Paul. Polycarp definitely wrote an epistle of his own, to the Philippians. St. Ignatius of Antioch, who was martyred at Rome in the first half of the second century, visited Smyrna and later wrote letters to St. Polycarp. And St. Irenaeus of Lyon (martyred ca. AD 202), who, as a boy, heard St. Polycarp preach, was probably a native of Smyrna.

This morning, we visited the most important historical structure of ancient Smyrna, its Agora, which is said to be (and I have no reason to doubt it) one of the best-preserved structures of ancient Ionia. Both my wife and I were amazed at how extensive and well displayed it was; our memories of when we first visited it many years ago agree that it was just a few rocks in a field of mostly dirt, scarcely worth visiting again.

After spending a fair amount of time visiting the heart of ancient Smyrna, we drove to Bergama. There we visited the Asclepion, the ancient temple of Aesculapius (the Greek god or demigod of medicine and of healing), one of the major “medical” centers of antiquity, where the great Galen (AD 129-216) received his basic training as a physician.

A larger-than-life-size statue of Galen adorns one of the intersections in Bergama. I was delighted to see it, not only because he became famous as a philosopher and as physician to Emperor Marcus Aurelius, but because he was perhaps the most prolific author of antiquity and because, in small part, the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative that I founded at Brigham Young University was involved with him.

After walking around the Asclepion, we ascended to the Acropolis of ancient Pergamum or Pergamon (Πέργαμον or, in modern Greek Pergamos [Πέργαμος]) by bus and by aerial tramway, where we walked about and examined such features as the city’s temple of Trajan.

The church of Pergamon, another of the famous seven churches – the northernmost of them — was praised for its forbearance (see Revelation 2:12-17) and some say that it was here that the first Christians were executed by Rome.

During the Hellenistic period, Pergamon became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon and one of the major cultural centers of the entire Greek world. The temple of Trajan, already mentioned, is merely one of the very impressive sights to be seen on the acropolis. But the most famous structure from the city is undoubtedly its monumental Great Altar, dating to the early second century before Christ, which was most likely dedicated either to Zeus or to Athena. The altar measures about 36 x 33 meters at its base. Its foundations can still be seen, but the high-relief frieze from it, roughly 2.3 meters high and 113 meters long, which depicts the Gigantomachy, the battle between the gods of Olympus and the Titans or giants, was carried away at the end of the nineteenth century to Germany. There it is housed in the magnificent Pergamonmuseum in Berlin – which, alas, is currently closed for renovations.

The reference at Revelation 2:13 to Satan’s “seat” or throne may allude to the great Pergamon Altar, which resembles a gigantic throne:

I know thy works, and where thou dwellest, even where Satan’s seat is: and thou holdest fast my name, and hast not denied my faith, even in those days wherein Antipas was my faithful martyr, who was slain among you, where Satan dwelleth.

Pergamon had the second-largest library in the Greco-Roman world, surpassed only by the Great Library at Alexandria. It is said to have housed a collection of approximately 200,000 scrolls. (To think of all the riches that were once there! The lost works of Aristotle! The lost plays of Sophocles! And on and on and on.) In fact, Pergamon was a center of parchment production, which reduced the Greco-Roman world’s dependence upon Egyptian papyrus; the very term parchment is derived from Pergamon.

One of the unexpected surprises of the day – I’ve never driven this particular route before – was to see the island of Lesbos. It was much closer than I had expected, although I’ve seen it plenty of times on a map. Seeing Lesbos got me to thinking about Sappho, and so I couldn’t resist reading her famous “Midnight Poem” to the patient and long-suffering people on the bus, who are unable to jump from the vehicle because it’s typically moving too fast and who, therefore, really have no place to go. I read it to them in both Greek and an English translation; for some reason, I find the Greek extraordinarily melancholy and affecting:

Δέδυκε μὲν ἀ σελάννα

καὶ Πληΐαδες, μέσαι δέ

νύκτες, πάρα δ’ ἔρχετ’ ὤρα,

ἔγω δὲ μόνα κατεύδω.The moon and the Pleiades have set.

It is midnight.

Time is passing,

but I sleep alone.

Posted from Kazdağları, Türkiye