It’s good to be back in Istanbul, one of my very favorite cities. One of my favorite places on Earth. (We flew in just a few hours ago, via Amsterdam.) I’m not sure how long it’s been since we were here last, but it could possibly have been as long as eight years. And my last visit to Turkey beyond Istanbul was probably eleven years ago. So I’m very happy to be back.

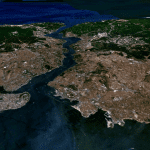

I love the setting of the city, virtually surrounded by water. (I can see water from my hotel window right now, bejeweled with the lights of the city.) Istanbul reminds me just a tiny bit of San Francisco or Seattle. I also love the fact that you can walk through very modern urban areas, then (in some parts of the city) turn a corner and find yourself very much in the Middle East. Most of all, though, I love its rich, layered history – notably from its time as the capital of the Christian eastern Roman Empire (eventually known to many, though not to its own residents, as the Byzantine Empire) and then as the capital of the Ottoman Empire, ruled over by Muslim Turks who had originally come from distant central Asia.

According to the classical historians, there has been a city here since its founding by Byzas of Megara in 667 BC. From him comes its original name, Byzantium, which eventually, even after the city’s refounding and renaming, gave us the “Byzantine” Empire. He is said to have been advised by the famous oracle of Apollo at Delphi to “settle opposite the land of the blind,” on the other side of the water — by which, supposedly, the area of Chalcedon was intended (because they blindly failed to notice the superior territory directly adjacent to them).

Between 512 BC and 488 BC, the Persians held Byzantium until it was liberated by the Spartan general Pausanius.

When Philip II of Macedon (the father of Alexander the Great) besieged the city in 340-339 BC, the residents of the city took many defensive measures. Among them was an appeal to the goddess Hecate, which included putting her symbols, the crescent moon and the star, on its coinage—which, some say, led to the adoption of those symbols, centuries later, by the Ottoman Turks and even by Islam more generally.

The Roman emperor Constantine I—yes, Constantine the Great—was acclaimed emperor by his troops in York, in the British Isles, after the death of his father, Constantius, and spent the first period of his reign fighting in what his now Germany and then in conflict with his co-emperors.

Once he was established as the sole ruler of the Empire, though, his attention had shifted to the east, where the biggest and longest lasting threat was that posed by, essentially, the Persians. Since the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire (which occurred essentially under Octavian or Augustus Caesar), the Senate had become more or less irrelevant, and the emperors, often out on military campaigns, rarely resided in Rome. Practically speaking, the capital was wherever the emperor happened to be.

Unlike the Chalcedonians of a thousand years before, during the lifetime of Byzas, Constantine recognized the enormous advantages conferred by Byzantium’s location. Located on a peninsula, it was protected by the sea on three sides. It sat on a sundered land bridge connecting Europe with Asia (offering an east-west trade route), and astride a series of easily defensible narrow water channels (the Bosporus and the Dardanelles or Hellespont) connecting the world of the Black Sea to that of the Mediterranean. It’s astonishing to me that it hadn’t already become the capital of an empire.

So Constantine established Νέα Ῥώμη (Nea Roma, Nova Roma, or “New Rome”) as his capital. Conveniently, like the original Rome, it included seven hills. Soon, though, it began to be called Κωνσταντινούπολις (Kōnstantinoupolis; “city of Constantine”).

By AD 476, one of the traditional dates for “the fall of Rome,” the authority of the government in Rome itself wielded, at most, negligible military, political, or financial power, and it held little if any sway over the scattered Western domains that could still be described as Roman. So, when the city fell, its fall had very little effect over the actual empire, for which the center of gravity had long since shifted eastward. The West is fascinated even today with “the fall of Rome,” perhaps, but those in the east still thought of themselves as Romans—significantly, using Greek rather than Latin: Romanoi—and the Muslim peoples called the Byzantine Empire Rūm (“Rome”). In a very real sense, then, the Roman Empire actually survived until AD 1453.

That was the year that the armies of the Ottoman Turks finally took the city under the twenty-three year-old sultan Mehmet the Conqueror and renamed it Istanbul. The Muslims had been at war with the Byzantines since the days of Muhammad in early seventh-century Arabia, and there had been at least two serious prior sieges by the Ottomans themselves. This time, though, they brought gunpowder and cannons with them, rendering the famous defensive walls of the city obsolete, and soon rendering large portions of them little more than rubble.

I quote from chapter 68 of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, by Edward Gibbon:

From the first hour of the memorable twenty-ninth of May [1453], disorder and rapine prevailed in Constantinople till the eighth hour of the same day, when the sultan himself passed in triumph through the gate of St. Romanus. He was attended by his vizirs, bashaws, and guards, each of whom (says a Byzantine historian) was robust as Hercules, dexterous as Apollo, and equal in battle to any ten of the race of ordinary mortals. The conqueror gazed with satisfaction and wonder on the strange though splendid appearance of the domes and palaces, so dissimilar from the style of Oriental architecture. In the hippodrome, or atmeidan, his eye was attracted by the twisted column of the three serpents; and, as a trial of his strength, he shattered with his iron mace or battle-axe the under jaw of one of these monsters, which in the eyes of the Turks were the idols or talismans of the city. At the principal door of St. Sophia he alighted from his horse and entered the dome; and such was his jealous regard for that monument of his glory, that, on observing a zealous Musulman in the act of breaking the marble pavement, he admonished him with his scimitar that, if the spoil and captives were granted to the soldiers, the public and private buildings had been reserved for the prince. By his command the metropolis of the Eastern church was transformed into a mosque: the rich and portable instruments of superstition had been removed; the crosses were thrown down; and the walls, which were covered with images and mosaics, were washed and purified, and restored to a state of naked simplicity. On the same day, or on the ensuing Friday, the muezin, or crier, ascended the most lofty turret, and proclaimed the esan, or public invitation, in the name of God and his prophet; the imam preached and Mohammed [Mehmet] the Second performed the namaz of prayer and thanks giving on the great altar, where the Christian mysteries had so lately been celebrated before the last of the Caesars. From St. Sophia he proceeded to the august but desolate mansion of a hundred successors of the great Constantine, but which in a few hours had been stripped of the pomp of royalty. A melancholy reflection on the vicissitudes of human greatness forced itself on his mind, and he repeated an elegant distich of Persian poetry:

” The spider has wove[n] his web in the Imperial palace, and the owl hath sung her watch-song on the towers of Afrasiab.”

Yet his mind was not satisfied, nor did the victory seem complete, till he was informed of the fate of Constantine [XI Palaiologos, the last of the Byzantine emperors]—whether he had escaped or been made prisoner, or had fallen in the battle. Two Janizaries claimed the honour and reward of his death: the body, under a heap of slain, was discovered by the golden eagles embroidered on his shoes; the Greeks acknowledged with tears the head of their late emperor and, after exposing the bloody trophy, Mohammed bestowed on his rival the honours of a decent funeral.

Posted from Istanbul, Türkiye