(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

We had a great day today. Rather long, but great. We began with the spectacular archaeological area of Saqqara, to the south of Cairo – but, of course, on the western side of the River Nile, the land of the setting sun and, thus, the abode of the dead. We did the usual Saqqara things but, on this time, we actually entered into the hugely important “step pyramid” of King Zoser (or Djoser) and looked down into his burial shaft at what is left of his sarcophagus. The shaft has been accessible to the public for approximately five years, but (for some reason) this was the first time that my wife and I have visited it.

Zoser’s pyramid is generally regarded as the key transition structure between the primitive mastaba tomb and the true pyramids that followed.

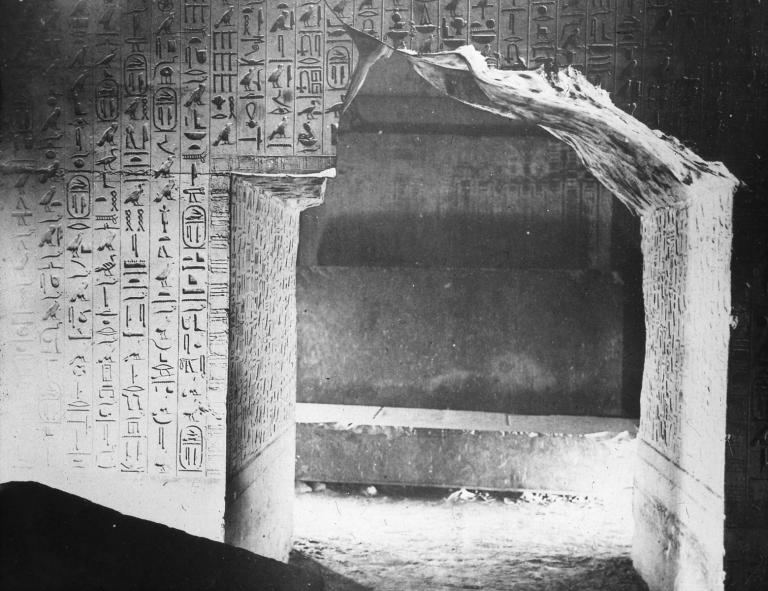

We then walked all around the step pyramid, including a look at a replica of a statue of the king gazing toward the North Star from his serdab on the pyramid’s north side. From there, we walked down to the ruined pyramid of king Unas (sometimes rendered as Wenis or Wanis [pronounced Wah-NEES], which is justly famous for the Pyramid Texts that were found inside it. Up until that discovery, the assumption (based on the pyramids of the Giza Plateau and elsewhere) was that pyramids never featured texts or illustrations. The inscriptions on the interior walls of the pyramid of Unas are beautifully carved.

Unas was the last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom, reigning for fifteen to thirty years in the mid-24th century BC (circa 2345–2315 BC).

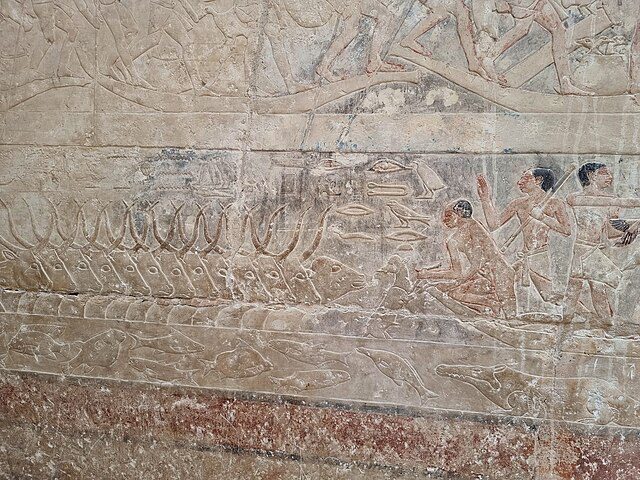

On our way back to the bus, we spent some time inside the mastaba tomb of Princess Sesheshet Idut, looking at the wall carvings there. She was probably a daughter of King Unas or Wanis, which explains the proximity of her tomb to his pyramid. When we lived in Cairo soon after our marriage, we had a close Egyptian friend who was (and is) an artist with a passion for the art of ancient Egypt. His wife was the Relief Society president for the Cairo Branch of the Church, and also a very good friend of ours. We spent many happy days visiting pharaonic-era tombs with them at Saqqara and Giza, and they had a cat that was named Edut, after the princess. They also had a son named Wanis, after Princess Idut’s apparent father.

One of my favorites among the carvings in Princess Idut’s tomb is the one shown just above, with its remaining original coloration. It depicts the clever way in which a herd of cattle (probably oxen or water buffaloes) are being induced to swim across a canal or across the River Nile. (Note the fish swimming below them, and the waiting crocodile, who would of course make them nervous.) A man is holding a calf on the opposite bank, to the right of the center of the image above. This is designed to encourage its mother to swim the water across in order to reach her baby. She can be seen, hornless and looking longingly at her calf, swimming toward it. And, thus led and encouraged, the others follow right behind her.

Then, having concluded our visit to Saqqara, we drove northward to Giza, where we walked to the base of the Great Pyramid of Khufu (or Cheops) and some actually entered into the pyramid itself. We ate lunch at the Pyramids Lounge, which was a first for us. (I think it’s very new; certainly it feels new.) The food was fairly good, but the view of the big three pyramids of Giza is magnificent. From there, it was camel riding at the pyramids for about an hour, and then a closing evening visit to a papyrus shop.

The weather here has been very pleasant, and the crowds have been manageable, the lines short. This seems to be a very good time to bring a tour group to Egypt.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I close, however, with a chilling entry from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™:

Paul S. Mueller, MD; David J. P. Levak, MD; and Teresa A. R. Ummans, MD, “Religious Involvement, Spirituality, and Medicine: Implications for Clinical Practice,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 76 (December 2001): 1225-1235. The authors were affiliated at the time that this article was published with the Division of General Internal Medicine, the Department of Anesthesiology, and the Section of Adult Psychiatry of the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minnesota.

Surveys suggest that most patients have a spiritual life and regard their spiritual health and physical health as equallyimportant. Furthermore, people may have greater spiritual needs during illness. We reviewed published studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and subject reviews that examined the association between religious involvement and spirituality and physical health, mental health, health-related quality of life, and other health outcomes. We also reviewed articles that provided suggestions on how clinicians might assess and support the spiritual needs of patients. Most studies have shown that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes, including greater longevity, coping skills, and health-related quality of life (even during terminal illness) and less anxiety, depression, and suicide. Several studies have shown that addressing the spiritual needs of thepatient may enhance recovery from illness. Discerning, acknowledging, and supporting the spiritual needs of patients can be done in a straightforward and noncontroversial manner. Furthermore, many sources of spiritual care(eg, chaplains) are available to clinicians to address the spiritual needs of patients.

Posted from Cairo, Egypt