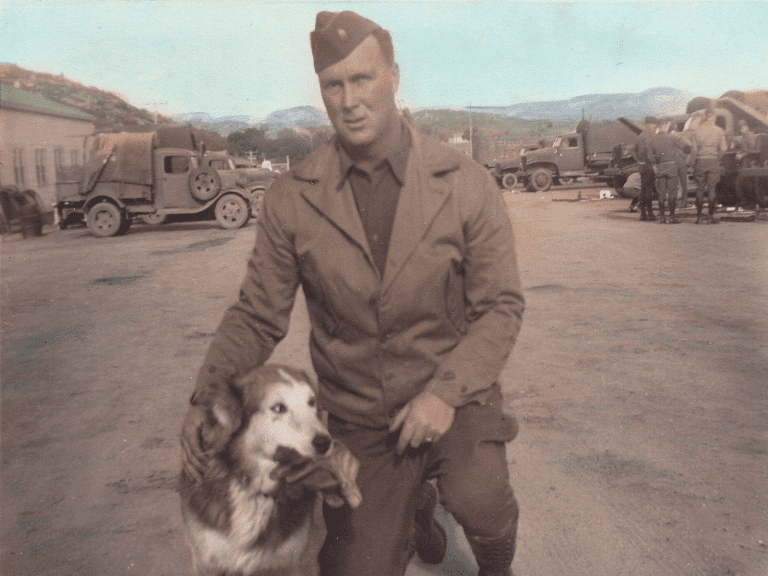

I recall my father expressing mild regret on one or two occasions for having failed to accept an invitation to attend officer candidate school in the Army. He hadn’t intended a military career, and he didn’t want to commit to officer training because he didn’t plan to be in the service for very long. He spent time in the horse cavalry — such a thing still existed in those days — and he was stationed near the border of California with Mexico on the day that Pearl Harbor was attacked. There were rumors that two Japanese divisions were about to cross over from Mexico into the United States, and so he and his fellow soldiers, who (I assume) were quite ill-equipped for such an encounter, were deployed to resist the invasion. Which, fortunately, never came.

With the commencement of World War II, Dad was suddenly in “for the duration.” One of his other occasional regrets was that, as he saw it, he was passed over for advancement to the rank of master sergeant in favor of an unqualified man who happened to be a friend of the officer who made the choice. So he remained a staff sergeant, instead.

Eventually, he was assigned to the Eleventh Armored Division in General George S. Patton’s Third Army. At the end of the Second World War, he found himself waiting in Paris — specifically, as I recall, in the suburban area of Le Vesinet, which I’ve visited in his honor — to be demobilized and sent home. He shared quarters there with at least three other non-commissioned officers.

On the evening that the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt was announced, two of the other sergeants drank themselves into a merry state. A third resident of their lodging, still sober, was a photographer for the Army newspaper The Stars and Stripes. The two were mugging for the camera, holding drunkenly on to each other and suggesting that the photographer label the photographs that he was taking with the caption “American Soldiers Mourn the Death of President Roosevelt.” He was snapping busily away as they struck various melodramatic poses.

My father watched their antics for a few minutes and then quietly asked the photographer, “You’re not actually planning to publish the photos of these two idiots, are you?” “Oh,” replied the photographer. “You don’t really think there’s film in this camera, do you?”

Thinking of this little anecdote at a remove of eight decades, I respond in a curious way: All of the four are, I presume, dead. Long dead. And yet, at one time, they were so very alive, their personalities so (literally) vivid. And it’s the collision between their personalities and the idea of “death” that I find odd. Although I know nothing beyond this slight story about either the photographer or the two drunken mourners, I find myself liking them. (I like people generally.) And, here as elsewhere, I find it oddly difficult to believe that human personalities are simply the accidental result of essentially random collocations of atoms, the product of pointless electrochemical processes — no different, fundamentally, than erosion or oxidation — and that they simply vanish when the synapses cease to fire.

At roughly the same time that my father was in the outskirts of Paris, on 15 May 1945, Charles Williams suddenly passed away. Himself a novelist and poet, and an editor at Oxford University Press, Williams had been one of C. S. Lewis’s closest friends and, with Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, a member of the famous Inklings. Lewis was deeply affected by his passing and wrote about it in a number of his letters to people like Owen Barfield, T. S. Eliot, and Dorothy Sayers. To “Sister Penelope,” an Anglican nun with whom he carried on a multi-year correspondence, he wrote the following in a letter dated 28 May 1945:

You will have heard of the death of my dearest friend, Charles Williams. . . .

Death has done nothing to my idea of him, but he has done–oh, I can’t say what–to my idea of death. It has made the next world much more real and palpable.

I have felt very much the same sentiment at the death of more than one friend or acquaintance, and even sometimes (as here) in the cases of people whom I didn’t personally know, and Lewis’s comment has always resonated with me.

My father participated in the liberation of this camp as part of the 11th Armored Division of Patton’s Third Army. (Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

When my father finally returned to the United States, he spent some time in Minneapolis (or St. Paul) waiting for a train connection back to his home state of North Dakota. (Sadly, his youngest brother, who struggled throughout life with alcohol, had mismanaged and lost the family farm, and his parents had moved out to Southern California to stay with others of their children who were already there. But he remained in North Dakota with his sister and her family for a short time before he himself returned to California, where he had taken up residence prior to enlisting in the Army.)

While in Minnesota waiting for his train, he sat in a bar. (His baptism into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — which I was privileged to perform the week I left on my mission, my [half-]brother, Dad’s stepson, doing the confirmation — was still nearly three decades in the future.) While he sat there, a group of young men, apparently of German extraction, somehow took it upon themselves to mock his account of the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen, in Austria. They had not fought in the war, evidently because of their young age and because, like his little brother, they had been the primary means of support for their aging parents,

They denied that such camps had existed. Or, if they existed, their horrors had been exaggerated. It was all, the young men claimed, just Allied war propaganda. They accused him of lying.

My father, who had photographically documented what his unit had found at Mauthausen (and at its subordinate camp, Gusen), and who suffered from nightmares about what he had seen for two years after leaving Austria — perhaps we would call it post-traumatic stress disorder today — was a gentle and soft-spoken man. I think that I only saw him really angry once in my life, when he intervened in a clear instance of abusive violence against a child. But he told me about that episode in Minnesota. He said that it was the closest he had ever come to being in a bar-room brawl.

I hate to see anti-Semitism and even Holocaust denial apparently on the rise. My father told me on more than one occasion that, someday, people would deny the reality of the Nazi camps. He had already experienced it, in Minnesota back in 1945. He wanted me to know that they had been real, that he had seen that reality. Honestly, I didn’t take his warning very seriously. How could such a thing be denied? I know better now.