Wikimedia Commons public domain photo

***

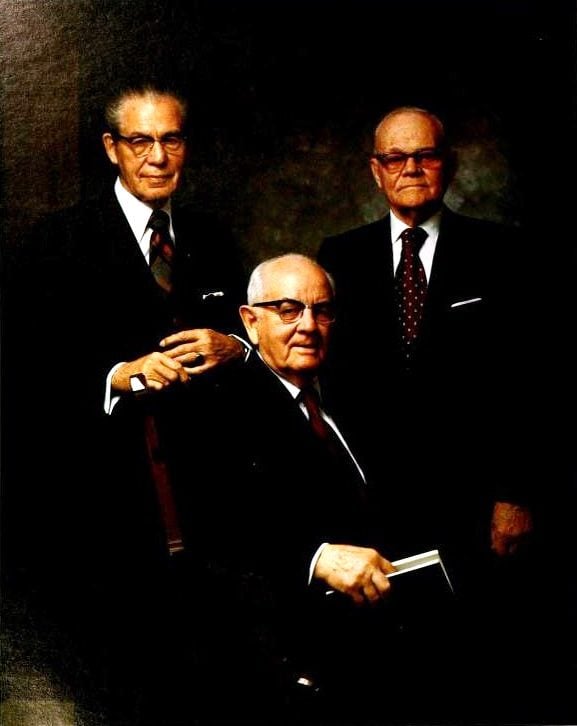

“The great religious leaders of the world such as Mohammed, Confucius, and the Reformers, as well as philosophers including Socrates, Plato, and others, received a portion of God’s light. Moral truths were given to them by God to enlighten whole nations and to bring a higher level of understanding to individuals. (The First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 15 February 1978)

***

I’m pretty commonly asked by Latter-day Saint audiences whether I believe that Muhammad was a genuine prophet of God, in the very strong Latter-day Saint sense and usage of that term. I typically respond with a resolute and forthright “I don’t know.” I simply can’t be certain. There are a few things that stand in the way of that conclusion for me, as a committed Christian and a believer in the claims of the Restoration. Notable among those obstacles is the Qur’an’s denial of the deity of Jesus. If it is true that the foremost and central task of a prophet is to testify of Christ, that is definitely a reason for me to withhold my endorsement. On the other hand, Muhammad and the Qur’an teach a very high and reverent view of Jesus. (Certainly far more so than other non-Christian religions, including Judaism.). So I typically add that I don’t rule out the idea that Muhammad was a prophet. In fact, I’m quite inclined to believe that he was inspired. Perhaps (though I have no evidence to make this stick), the sources as we have them don’t even accurately represent his actual teaching. Moreover, there is always the possibility that, while he was genuinely inspired, Muhammad’s revelations (as we have them) don’t inerrantly represent that inspiration.

With regard to that last possibility, which would fall considerably short of long-standing Muslim orthodoxy but would be a far more positive view than most Christians have historically entertained, I find the thinking of the great Edinburgh Islamicist W. Montgomery Watt (1909-2006) of considerable interest. Watt was both a deeply sympathetic student of Islam and biographer of Muhammad and an Anglican priest. He was manifestly very willing to viewing Muhammad and the Qur’an as inspired, but he did not accept traditional Islamic views of them as infallible. It was probably as difficult for him as it is for me to accept certain Qur’anic and Islamic doctrines (e.g., on the divinity of Christ). In 1970, Watt published a revised edition of Richard Bell’s 1953 Introduction to the Qur’an. Like W. M. Watt, Richard Bell (1876-1952) had been both an Islamicist at the University of Edinburgh and an ordained priest. These notes on the nature of Qur’anic revelation come from W. M. Watt and R. Bell, Introduction to the Qur’an, 18-25. Something on this topic should, I think, appear in the heavily revised book on Islam that I’m preparing for a Latter-day Saint audience; these notes are preparatory to that.

***

What does the Qur’an say about the nature of revelation? What are the principal words (nouns and verbs) that the Qur’an uses to refer to revelation?

Qur’an 2:97 is an interesting passage in this regard:

Gabriel “sends it down [nazzalahu] upon your heart by God’s permission [bi-idhni Allah]

“one of the latest and clearest descriptions of revelation in the Qur’an” (Watt and Bell, 18-19)

“That this was the account accepted by Muhammad and the Muslims in the Medinan period is certain. Tradition is unanimous on the point that Gabriel was the agent of revelation. When Tradition carries this back to the beginning, however, and associates Gabriel with the original call to prophethood, the scholar’s suspicions are aroused since Gabriel is only twice mentioned in the Qur’an, both times in Medinan passages. The association of Gabriel with the call appears to be a later interpretation of something which Muhammad had at first understood otherwise” (Watt and Bell, 19).

“It is to be noted that in 2.97/1 there is no assertion that Gabriel appeared in visible form; and it may be taken as certain that the revelations were not normally mediated or accompanied by a vision” (Watt and Bell, 19).

The Qur’an mentions two occasions on which Muhammad saw a vision:

53:1-12

53:13-18

“Strictly read, these verses imply that the visions were of God, since the word ‘abd, ‘slave’ or ‘servant’, describes a man’s relation to God and not to an angel; this interpretation is allowed by some Muslim commentators” (Watt and Bell, 19).

In 81:15-25, however, the vision or visions seem to be reinterpreted as visions of an angel.

“This indicates a growing and changing understanding of spiritual things in the mind of Muhammad and the Muslims. At first they assumed that he had seen God himself, but later they realized that that was impossible, and therefore concluded that the vision was of a messenger of God, that is, an angel” (Watt and Bell, 19)

There is perhaps one other allusion, in the Qur’an, to a vision. It occurs before the expedition to Hudaybiyya:, in 48:27.

See also Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks. “The Throne Theophany/Prophetic Call of Muhammad.” In The Disciple as Scholar: Essays on Scripture and the Ancient World in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson.

http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/publications/books/?bookid=46&chapid=253

From the hadith:

Seeing God and the sun on the horizon.

Moses and God’s index finger.

According to Watt and Bell, 23, there are four phases in Muhammad’s understanding of revelation:

- God himself appears and speaks.

- A spirit implanted within him speaks.

- Angels and intermediaries speak.

- Gabriel is the angelic intermediary who speaks.

“Both the visible appearance of God and the hearing of his voice are excluded by 42.51/0: ‘it is not fitting for any human being that God should speak to him except by “revelation” [illa wahyan] or from behind a veil [hijab], or by sending a messenger to “reveal” [fa-yuuhiya] by his permission what he will’” (Watt and Bell 19-20).

“The Arabic verb and noun, awha and wahy, have become the technical terms of Islamic theology for the communication of the messages or revelations to Muhammad” (Watt and Bell, 20).

Bell’s translation renders awha/yuuhi as “to suggest.”

But, in the Qur’an, the word awha is also used in 19:11/12 with regard to Zechariah or Zacharias, who had been stricken dumb, making a “sign” or “indicating” to the people that they should glorify God.

Satans or demons among jinn and men “suggest” specious ideas to one another, according to 6:112.

Moreover, the recipient of wahy from God isn’t always a prophet, nor even human. In 16:68/70, God “suggests” to the bee to take houses for herself in the hills and trees and in the arbors that men erect. At the Last Day, according to 99:2-5, the earth will yield up its burdens because its Lord has “suggested” that it do this.

In 41:12/11, God “suggested” its specific function to each of the seven heavens.

Even when the recipient of wahy is a human prophet, the “suggestion” may not be a verbal revelation, but, rather, a practical course of action. Something to do, not something to say.

In 11:36/8 and 23:27, for example, it is “suggested” to Noah that he build the ark, and he is to build it under God’s eyes and at God’s “suggestion.”

To Moses, it is “suggested” that he set out with his people by night (20:77/9; 26:52), strike the sea with his staff (26:63), strike the rock with his staff ((7:160).

To Muhammad himself, it is “suggested” that he should follow the religion of Abraham (16:123/4).

Still, these practical “suggestions” are often formulated in direct speech, as if a form of words had been put into a person’s mind (see, for example, 17:39/41 and the verses preceding it).

Sometimes, the terms appear with reference to doctrine rather than conduct.

“your God is one God” (18:100; 21:108; 41:6/5”

“Usually the formula is short, the sort of phrase which after consideration of a matter might flash into a person’s mind as the final summing up and solution of it. . . . The fundamental sense of the word as used in the Qur’an seems to be the communication of an idea by some quick suggestion or prompting, or, as we might say, by a flash of inspiration. This agrees with examples given in the dictionaries (such as Lisan al-‘Arab, s.v.) where it is implied that haste or quickness is part of the connotation of the root” (Watt and Bell, 20-21).

There are, however, a few passages in which the verb seems to refer to the communication of relatively lengthy matters to the Prophet.

For example, in 12:102/3 the phrase “stories of what is unseen [or absent]” may refer to the entire story of Joseph. “Even in such passages, however, the actual verbal communication of the stories is not certainly implied” (Watt and Bell, 21).

“An explanation of the frequent use of this term in connection with the Prophet’s inspiration might be that there was something short and sudden about it. If Muhammad was one of those brooding spirits to whom, after a longer or shorter period of intense absorption in a problem, the solution comes in a flash, as if by suggestion from without, then the Qur’anic use of the word becomes intelligible. Nor is this merely a supposition. There is evidence to show that the Prophet, accessible enough in the ordinary intercourse of men, had something withdrawn and separate about him. In the ultimate issue he took counsel with himself and followed his own decisions. If decisions did come to him in this way, it was perhaps natural that he should attribute them to outside suggestion” (Watt and Bell, 21).

Richard Bell hypothesized that “originally the wahy was a prompting or command to speak. The general content of the utterance was perhaps ‘revealed’ from without, but it was left to Muhammad himself to find the precise words in which to speak” (Watt and Bell, 22).

“Sura 73.1-8 was interpreted by Bell of the Prophet taking trouble over the work of composing the Qur’an, choosing the night-hours as being ‘strongest in impression and most just in speech’, that is, the time when ideas are clearest and when fitting words are most readily found” (Watt and Bell, 22).

“A similar experience when after effort and meditation the words in the end came easily as if by inspiration, may well have led him to extend to the actual words of his deliverances this idea of suggestion from without” (Watt and Bell, 22).

“A curious isolated passage [75:16-19] seems to encourage him to cultivate this deliberately: ‘Move not thy tongue that thou mayest do it quickly; ours it is to collect it and recite it; when we recite it follow thou the recitation; then ours it is to explain it’. This has always been taken as referring to the reception of the Qur’an, and if we try to get behind the usual mechanical interpretation we can picture Muhammad in the throes of composition. He has been seeking words which will flow and rhyme and express his meaning, repeating phrases audibly to himself, trying to force the continuation before the whole has become clear. He is here admonished that this is not the way; he must not ‘press’, but wait for the inspiration which will give the words without this impatient effort to find them. When his mind has calmed, and the whole has taken shape, the words will come; and when they do come, he must take them as they are given him. If they are somewhat cryptic—as they may well happen to be—they can be explained later” (Watt and Bell, 22).

“If that be the proper interpretation of the passage, it throws light on a characteristic of the Qur’an which has often been remarked on, namely, its disjointedness. For passages composed in such fashion must almost of necessity be comparatively short” (Watt and Bell, 22).

“In some such way, then, Muhammad’s claim to inspiration might be understood. It has analogies to the experience which poets refer to as the coming of the muse, or more closely to what religious people describe as the coming of guidance after meditation and waiting upon God” (Watt and Bell, 22).

Muhammad was genuinely convinced that his inspiration came from God (Watt and Bell, 23, 24-25).

But he may also have been aware of the danger that his “inspiration” could come from a non-divine source—e.g., from the devil or even from within himself. He had to be reassured that he was not majnun (that is to say, not mad, or not jinn-possessed).

The matter of the “Satanic verses.”

There is a danger of trying to hasten things. (See 18:24.)

Some questions should perhaps not even be asked. (See 5:101; 22:52.)

A‘isha’s complaint that the Lord hastens to do Muhammad’s desire (Watt and Bell, 24).

But there are revelations that criticize him, that urge him to do things he didn’t want to do (Watt and Bell, 24).

Nazzala and anzala also need to be examined, though. They are three times as common as awha. Bell’s hypothesis doesn’t account for them. But they’re probably compatible with his hypothesis about wahy. (Watt and Bell, 24.)

Posted from Park City, Utah