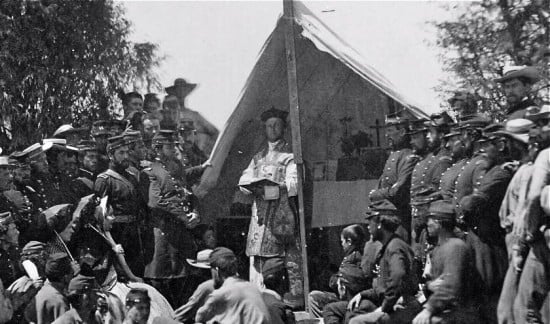

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War, and at least one historian has taken the time to look at religion’s role in the war:

“One of the things that surprised me was that there were certain dominant ideas, regardless of particular religious affiliation. Ideas about providence, ideas about sin, ideas about judgment. Those were common themes that crossed religious traditions,” George C. Rable, a history professor at the University of Alabama, told CNA on Dec. 7.

“Religion was absolutely pervasive when Americans tried to explain the causes, and the course, and the consequences of the Civil War.”

The year 2011 marks the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865.

The conflict remains a central event in American history. It preserved the union of the states and emancipated the slaves, both actions which Christians saw at the time as providential.

Differences about slavery and whether it was a divinely inspired institution helped divide the Protestant churches before and during the war. Some contemporary Catholic observers saw these divisions as a religious fault.

Prof. Rable, author of the 2010 book “God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War” (Univ. of North Carolina Press, $35), read many northern Catholic newspapers from the period for his research.

“One argument that they make is that essentially Protestantism caused the war. You might say that that is a peculiar idea, but their point was that Protestants are inherently divisive and schismatic. Had the nation been entirely Catholic, they said, the nation would never have divided.”

Catholics were a relatively small minority and tended to side with the people in their own section.

Contemporary Catholics, especially in the North, were “especially fascinating” to Rable because they did not speak in one voice and became increasingly divided as the war went on.

“Some remained very conservative, almost Copperhead in orientation, while somebody like Orestes Brownson came out against slavery early in the war and became a strong supporter of the Lincoln administration,” he said.

The anti-Catholicism of the 1850s accompanied the rise of the nativist Know Nothing Party, which contributed to Catholic fears.

“One of the things more conservative Catholics say during the war is, ‘you can’t trust the Republicans, because after they are through with the Confederates they’ll turn on the Catholics,’” Rable explained.