I suspect a lot of people don’t know about this period of his life. Author Stephen Mansfield has the details:

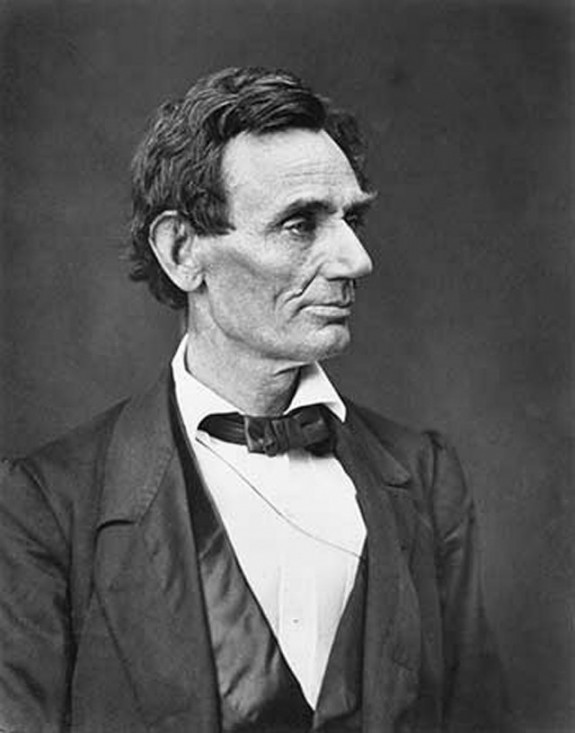

We have heard the soaring phrases often. They are fixed in the American book of verse. Now, they sound again in Steven Spielberg’s magnificent film, “Lincoln.”

They come to us as tones of faith from Abraham Lincoln’s presidential speeches: “a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land,” “the Almighty has his own purposes,” “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom,” and “the judgments of the Lord are true.” They suggest a God who rules in the affairs of men and does so with both love and justice.

Yet this God was not always Abraham Lincoln’s God. In his early years, Lincoln hated this being. It was a natural response. He was thoroughly convinced that God, in turn, hated Abraham Lincoln. It is one of the most surprising facts of Lincoln’s life, a fact that makes his religious journey among the most unique in our history.

The 16th president of the United States was born on an American frontier swept by almost violent religious revivals. Men routinely responded to preaching and the “Spirit’s work” by shouting, convulsing, passing out and even barking. Few were caught up in this excitement more eagerly than Thomas and Nancy Lincoln.

Their intelligent, sensitive son found it all too much. Young Abraham rejected his parents’ loud, sweaty brand of faith and in part because he could not reconcile the weepy, religious version of his father with the man who beat him, worked him “like a slave,” and resented his dreams of a more meaningful life. Historian Allen Guelzo has written, “on no other point did Abraham Lincoln come closer to an outright repudiation of his father than on religion.”

Young Abraham chose reading over religion — and reading made him rethink religion. Alongside “Aesop’s Fables” and “Robinson Crusoe,” he read the works of religious skeptics. Books like Thomas Paine’s “Age of Reason,” Edward Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” and “Ruins” by the French writer Volney gave Lincoln the intellectual tools for dismantling the edifice of religion.

His move to the Illinois village of New Salem did the same. As his friend and biographer, William Herndon, wrote of this time, “he was surrounded by a class of people exceedingly liberal in matters of religion. Volney’s ‘Ruins’ and Paine’s ‘Age of Reason’ passed from hand to hand.” Lincoln drank deeply from this anti-religion stream. Soon he began openly attacking Christianity. Friends recalled that he openly criticized the Bible, that he called Christ a bastard and that he labeled Christianity a myth. He even wrote a pamphlet defending “infidelity.” To protect his political aspirations, friends tore the booklet from his hands and burned it. Lincoln was furious. He had become the village atheist…

…Lincoln lived under this angry cloud during his first ventures into politics, into a troubled marriage and through the sufferings that marred his life and assured him of his curse. Oddly, it was through the portal of these very sufferings that faith slowly returned.

Read about his conversion here.