In New York City, Steven McDonald is something of a legend. His story grabbed the headlines nearly 30 years ago, in connection with a crime that shocked and horrified many in the city. If you don’t know his story, you should:

When NYPD officer Steven McDonald entered Central Park on the afternoon of July 12, 1986, he had no reason to expect anything out of the ordinary. True, there had been a recent string of bicycle thefts and other petty crimes in the area, and he and his partner, Sergeant Peter King, were on the lookout. But that was a routine – all in a day’s work. Then they came across a cluster of suspicious-looking teens.

When they recognized us as cops, they cut and ran. We chased after them, my partner going in one direction and I in another. I caught up with them about thirty yards away. As I did, I said to them, “Fellas, I’m a police officer. I’d like to talk with you.” Then I asked them what their names were and where they lived. Finally I asked them, “Why are you in the park today?”

While questioning them I noticed a bulge in the pant leg of the youngest boy – it looked like he might have a gun tucked into one of his socks. I bent down to examine it. As I did, I felt someone move over me, and as I looked up, the taller of the three (he turned out to be 15) was pointing a gun at my head. Before I knew what was happening, there was a deafening explosion, the muzzle flashed, and a bullet struck me above my right eye. I remember the reddish-orange flame that jumped from the barrel, the smell of the gunpowder, and the smoke. I fell backward, and the boy shot me a second time, hitting me in the throat. Then, as I lay on the ground, he stood over me and shot me a third time.

I was in pain; I was numb; I knew I was dying, and I didn’t want to die. It was terrifying. My partner was yelling into his police radio: “Ten Thirteen Central! Ten Thirteen!” and when I heard that code, I knew I was in a very bad way. Then I closed my eyes…

Steven doesn’t remember what happened next, but when the first officers to respond arrived on the scene, they found Sergeant King sitting on the ground, covered in Steven’s blood, cradling him in his arms and rocking him back and forth. He was crying. Knowing that every wasted second could be fatal, the men heaved Steven into the back of their RMP and rushed him to the nearest emergency room, at Harlem’s Metropolitan Hospital, twenty blocks away.

Immediately EMT’s, nurses, and doctors went to work. For the next forty-eight hours, he hung between life and death. At one point, Steven’s chief surgeon even told the police commissioner, “He’s not going to make it. Call the family. Tell them to come say goodbye.” But then he turned a corner.

They did the impossible: they saved me, but my wounds were devastating. The bullet that struck my throat had hit my spine, and I couldn’t move my arms or legs, or breathe without a ventilator. In less than a second, I had gone from being an active police officer to an incapable crime victim. I was paralyzed from the neck down.

When the surgeon came into my room to tell me this, my wife, Patti Ann, was there, and he told her I would need to be institutionalized. We had been married just eight months, and Patti Ann, who was 23 at the time, was three months pregnant. She collapsed to the floor, crying uncontrollably. I cried too, though I was locked in my body, and unable to move or to reach out to her.

Steven spent the next eighteen months in the hospital, first in New York and then in Colorado. It was like learning to live all over again, this time completely dependent on other people. There were endless things to get used to – being fed, bathed, and helped to the bathroom.

Then, about six months after I was shot, Patti Ann gave birth to a baby boy. We named him Conor. To me, Conor’s birth was like a message from God that I should live, and live differently. And it was clear to me that I had to respond to that message. I prayed that I would be changed, that the person I was would be replaced by something new.

That prayer was answered with a desire to forgive the young man who shot me. I wanted to free myself of all the negative, destructive emotions that his act of violence had unleashed in me: anger, bitterness, hatred, and other feelings. I needed to free myself of those emotions so that I could love my wife and our child and those around us.

Then, shortly after Conor’s birth, we held a press conference. People wanted to know what I was thinking and how I was doing. That’s when Patti Ann told everyone that I had forgiven the young man who tried to kill me.

He is reportedly the most seriously injured member of the NYPD to ever survive his injuries.

Since then, Officer McDonald has devoted himself to a number of causes. He and his wife co-wrote a book about their life. He makes frequent appearances to lend his name and face to various Catholic charities (His son, Conor, was named for Cardinal John O’Connor, who supported the family through his ordeal; Conor himself is now a member of the NYPD).

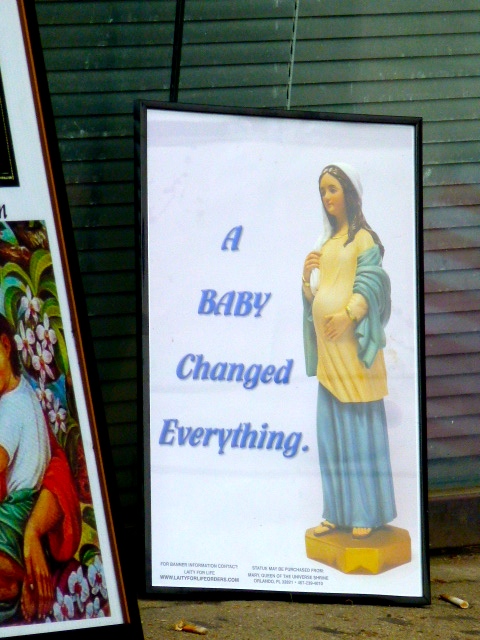

Steven McDonald is also proudly pro-life. Which is why he turned up at my parish in Queens this morning to join a march sponsored by Msgr. Philip Reilly’s “Helpers of God’s Precious Infants.”

Officer McDonald led several decades of the rosary as about 50 of us processed from my parish to an abortion clinic several blocks away, where we prayed, sang hymns and offered a moment of silence in support of the unborn. At least one woman who was about to enter the clinic changed her mind.

I don’t know how many people recognized the figure in the blue poncho rolling by in a wheelchair. Few, I suspect, realized they were in the presence of a genuine hero, a man of remarkable courage and unyielding faith—a figure whose name to many in the city is synonymous with a horrific, violent crime, but who has made his very existence a witness for peace and a testament to life.

Steven McDonald, even confined to his wheelchair, stands taller than most of us.

This Memorial Day weekend, he deserves to be remembered.

So, too, does Msgr. Reilly, a humble and determined priest of Brooklyn who has turned his quiet, peaceful form of protest into a global movement centered on prayer and, quite simply, presence. Those who are familiar with his work know his ministry is non-confrontational, obedient, faith-filled, and Eucharist-centered. Every march begins with Mass and ends with Benediction. And in between, there is the simplest and most recognizable form of prayer: the rosary. The woman who gave life to our salvation, the Mother of God, is invoked again and again. “Pray for us now and at the hour of our death, Amen.” Death is never far from our minds when we walk the streets to pray for the unborn. We are mindful of our mortality. But we are also reminded of the gift of life. The gift of reconciliation. The blessing of hope.

The woman who changed her mind this morning did so, in no small measure, because of the quiet and persistent work of Msgr. Reilly. He has been a powerful witness to life, across many decades. Lest we forget, his greatest weapon has been the one he carried with him this morning on the streets of Queens.