When Patheos first explored questions about the future of religion five years ago, I speculated that a Catholic priesthood made up of more married men was likely. Well, five years later, married men are continuing to be ordained—through the Pastoral Provision created by St. John Paul II and via the Anglican Ordinariate set up by Benedict XVI—but a bigger impact on the future of the church may lie, not in the priesthood, but in the church’s bishops.

What a difference a pope makes.

The election of Jorge Bergoglio as Bishop of Rome has changed more than just the man waving from the balcony of St. Peter’s. In ways both subtle and dramatic, it’s changing the shepherds leading the local flocks. Pope Francis has famously said shepherds should “live with the smell of their sheep,” and he seems intent on appointing men who do just that.

We shouldn’t be surprised that a pope puts his own stamp on the episcopacy. Pope Benedict often selected as bishops men who were not unlike himself: scholars, academics, teachers, intellectuals. Many of the men he appointed had some background in seminary formation. He seemed to be trying to craft a teaching church and therefore appointed men who could also help foster vocations.

Pope Francis, on the other hand, appears to be selecting men who are first and foremost pastors. Many have extensive experience working in parishes. They’ve done their share of weddings, baptisms, funerals; they’ve had to attend parish council meetings and replace broken boilers. They’ve counseled couples, heard confessions, dried the tears of grieving widows. Don’t look too hard for cufflinks; these guys usually work with their sleeves rolled up.

Take a deep breath and you won’t smell just Old Spice and incense. You’ll also smell the sheep.

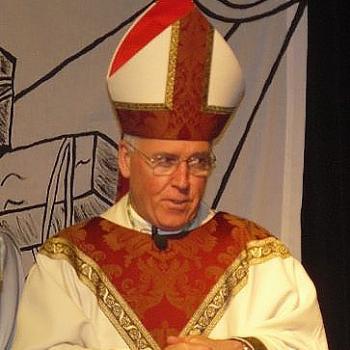

Take, for example, the new bishop of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Edward Malesic, whose clerical career has involved primarily parish and college ministry:

He began doing student ministry at various local colleges.

“My job was simply to put together the best Catholic church we could” on campus, he said. It was also to let students “ask their questions and letting them have their doubts.” Listening and discussing built strong connections with students, he said.

Father Malesic also enjoyed parish work. When his bishop asked him to study canon law, Father Malesic worried about being stuck behind a desk. But he found there was a “pastoral side” even there, helping people receive marriage annulments and other services.

His most recent assignment was as pastor of Holy Infant Church in York Haven, York County.

“He’s an extremely spiritual guy, but he’s also very people centered,” said Joe Kramer, a deacon at Holy Infant. “He’s not afraid to get down from the pulpit and get along with the sheep.”

Then there is Bernard Hebda, coadjutor Archbishop for Newark who, before becoming a bishop, worked in Pittsburgh as an assistant pastor, a pastor, and then director of the Newman Center, before teaching in Rome. (It doesn’t hurt that he also served as a secretary to Pittsburgh’s Donald Wuerl early in his career, or that he likes people to simply call him “Bernie.”) Before he entered the seminary, he collected degrees from Harvard and Columbia, and worked as a lawyer.

Or there’s Bishop Thomas Daly of Spokane, who worked as a parochial vicar, pastor, police chaplain and high school campus minister before becoming an auxiliary bishop.

It’s always risky to make generalizations about popes, and just two years into this papacy a clear portrait of a “Francis bishop” is still being sketched. But I think it’s fair to say we’re in for some surprises, and we’ll be seeing men in high places with diverse priorities and personalities. It’s too soon to tell just what the full impact of these kinds of appointments might be. It cannot help but affect the dynamic between the shepherds and their flocks; it may also affect the kinds of men who find themselves drawn to the priesthood. Might this bring about a new generation of “worker-priests”? Could this also have a ripple effect on the diaconate? Stay tuned.

This much is certain: some fundamental change is underway—and it could transform the church and her clergy for decades.

Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on the Future of Catholicism in America. Read other perspectives here.