A sobering and, frankly, shocking assessment from a combined analysis of The Boston Globe and Philadelphia Inquirer:

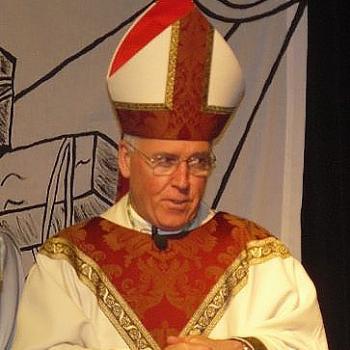

Bishop Robert Finn wasn’t going anywhere.

He never alerted authorities about photos of young girls’ genitals stashed on a pastor’s laptop. He kept parishioners in the dark, letting the priest mingle with children and families. Even after a judge found the bishop guilty of failing to report the priest’s suspected child abuse — and after 200,000 people petitioned for his ouster — he refused to go.

“I got this job from John Paul II. There’s his signature right there,” Finn had told a prospective deacon shortly after the priest’s arrest in 2011, pointing to the late pontiff’s photo. “And that’s who I answer to.”

Sixteen years after the clergy sexual-abuse crisis exploded in Boston, the American Catholic Church is again mired in scandal. This time, the controversy is propelled not so much by priests in the rectories, as by the leadership, bishops across the country who like Finn have enabled sexual misconduct or in some cases committed it themselves.

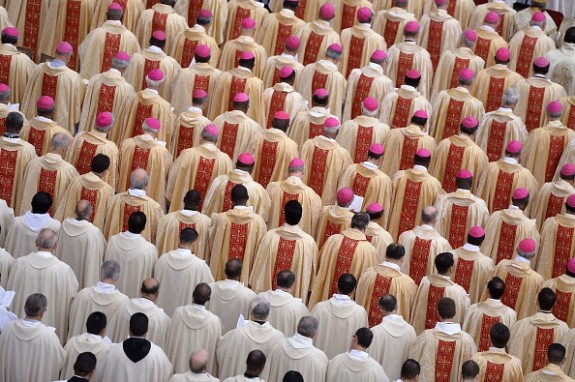

More than 130 U.S. bishops – or nearly one-third of those still living — have been accused during their careers of failing to adequately respond to sexual misconduct in their dioceses, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer and Boston Globe examination of court records, media reports, and interviews with church officials, victims, and attorneys.

At least 15, including Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington who resigned in July, have themselves been accused of committing such abuse or harassment.

Most telling, the analysis shows that the claims against more than 50 bishops center on incidents that occurred after a historic 2002 Dallas gathering of U.S. bishops where they promised that the church’s days of concealment and inaction were over. By an overwhelming though not unanimous vote, church leaders voted to remove any priest who had ever abused a minor and set up civilian review boards to investigate clergy misconduct claims.

But while they imposed new standards that led to the removal of hundreds of priests, the bishops specifically excluded themselves from the landmark child-protection measures. They contended that only the pope had authority to discipline them and said peer pressure — public or private shaming they euphemistically called “fraternal correction” – would keep them in line.

It hasn’t.