Divergent opinions regarding the virtues and vices of Prometheus have fueled rigorous online debates. While some were captivated by Ridley Scott’s imaginative vision, others laughed in all the wrong places. Prometheus was burdened by massive expectation. Yet, when filmmakers dare to spin a new creation myth, rigorous critique will follow. So does Prometheus present a fresh take on the origins of humanity or does it play with profundity in service of a silly sci-fi story?

I will split the difference, calling Prometheus a semi-smart movie about human stupidity. The timing of this speculative film is heightened by scientists’ confirmation of an Higgs boson. We continue to wonder how the universe works and where we came from. While Prometheus rightly critiques our blind faith in technology, it ultimately fails to provide satisfying answer about where we’ve been and where we’re headed as humanity.

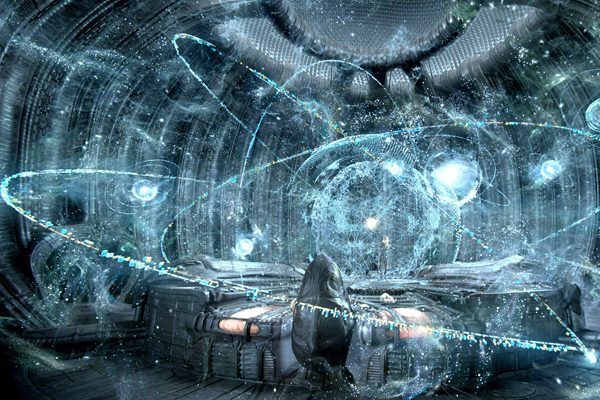

Director Ridley Scott creates a spellbinding atmosphere in the first third of the film (warning: massive spoilers ahead!). The provocative prologue suggests that humanity descends from the stars, or at least from a buff extraterrestrial race. This is the titular Prometheus, playing with fire and seeding the earth with what we now recognize as human DNA. The origins of the spaceship that departs following his plunge leave his intentions slightly open ended. Had he been consigned to death as a form of punishment or does he choose to sacrifice himself for a greater good? His suicide may be seen as the ultimate rebellion against the evil engineers (but for humanity as we know it, a fortunate fall). Many loaded theological possibilities (and Christ-like parallels) arise from this alternative creation story.

Flash-forward to the future where two archeologists discover cave paintings that point to a group of stars. This invitation across eons sparks a trillion dollar investment from Weyland Industries and a trip to planet LV-223. Along the journey, we meet the most compelling character in Prometheus, a cyborg named David, doing homework in preparation for the mission ahead. To pass the two-years of space travel, David watches Lawrence of Arabia, modeling his look and tones after the dashing Peter O’Toole. David replays a crucial scene where Lawrence is asked how he has learned to play with fire. Lawrence’s response is telling, “The trick is not minding it hurts.” As in all Alien films, plenty of people are sure to get hurt.

I was prepared to be scared but came away surprised by how tame Prometheus seemed. It is more ponderous than pulse pounding. Perhaps our collective hopes were too high for a prequel to a revered science fiction series. I still remember the visual shock that arose from Ridley Scott’s original Alien in the summer of 1979. The Nostromo felt like a blue-collar ship of space miners, out for a routine mission, hauling ore. So the horrors that grew from a tiny egg snuck up on audiences. H.R. Giger’s biomechanical alien felt like a chilling evolutionary possibility. And Sigourney Weaver’s ferocious Ripley set an aggressive new standard for screen heroines. Speculation about the origins of the space jockey left filmgoers eager for more. After five Alien movies, Prometheus could no longer sneak up on audiences. We expect xenomorphs to burst forth from inside something or someone. The tension in Prometheus builds slowly. Nothing splatters for almost half the movie.

Noomi Rapace steps into Ripley’s sizable shoes as lead archeologist, Elizabeth Shaw. While Rapace conveys the same feral intensity she brought to the Stieg Larsson Millennium films, her fellow scientists come across as remarkably stupid. Who would be foolish enough to remove their helmet because it seems like the atmosphere on a far-flung planet has been rigged to resemble ours? Why does the designated mapmaker get lost? Why do crew members who separate from the group because they’re creeped out go back to the place that creeped them out? And what kind of scientist would greet a snake-like alien as if it is a cuddly plush toy? Dumb and Dumber get what they deserve. An Ice Princess (Charlize Theron) wants to inherit Daddy’s empire. The rugged Captain (Idris Elba) just wants to get his ship and crew back to earth intact. Elizabeth commits the most egregious procedural errors. Having hauled the head of an ancient space jockey back to the ship, she proceeds to dissect, analyze, and then blow up her specimen, destroying an archaeological breakthrough within two minutes.

Only the cyborg comes off looking intelligent. David accompanies the crew on their surface mission, gathering samples with childlike glee. The moment when he stretches a mysterious goo between his fingers encapsulates the entire franchise in a frame. He offers the simple truth, “Big things have small beginnings.” David also takes directions with a chilling logic, spiking an archeologists’ drink only after Charlie swears a willingness to do anything to find answers. Irish actor Michael Fassbender makes us root for David, eager to see what happens with his experiments.

Is it a problem when we’re rooting more for the non-humans than the crew? Dramatically speaking, yes. In the second half of the film, we wait and wonder who will be killed next. Not because we care about the characters, but because we want to get past the carnage to the overall point. Thematically speaking, the stupidity of the scientists is the point. Prometheus is a cautionary tale about the dangers of biotechnology. Breaking the DNA chain can create problems. The engineers turn out to be bioterrorists constructing cosmic weapons of mass destruction. And evidently, in playing with fire, they got burned. Now it is our turn.

Who or what is our postmodern Prometheus? The movie points to technologists like Peter Weyland. As funder of the mission, Guy Pearce hides behind some awkward old man make up that recalls 2001 but ends up more like Benjamin Button. Prior to Prometheus’ release, a brilliant viral video marketing campaign revealed the young Weyland’s Ted Talk circa 2023. He links his efforts to technological advances throughout history. But the movie never makes it clear if Weyland is searching for the fountain of youth or just a shortcut to heaven. He is our Prometheus, placing too much faith in technology and its ability to grant us immortality.

So where should we place our faith? Elizabeth wears a cross, given by her father. He beliefs are never articulated as much beyond ‘faith’. But the true believers are proven to be foolish. They followed the signs which pointed to a distant planet. So why would the engineers call us to the place where they were preparing our destruction? Were these paintings done by the rebel Prometheus as a pre-warning of peril to follow? Or just a convenient way for the screenwriters to move viewers from prehistoric cave paintings into deep space?

Science, in the form of Darwinism, is presented as the enemy of the cross. Will our choices remain religion versus science? What a 20th century way of thinking! With physicists confirming the existence of an Higgs boson, Internet discussion of the so-called ‘God particle’ will be effusive. (For an accessible video introduction, watch this). Our general ignorance of astronomy and physics will allow skeptics and believers to each claim that science confirms their faith. But why must we default to the old Genesis versus science debate? The rigorous researchers at the Fermilab and CERN are addressing “how” questions, trying to identify how matter adheres. The Bible is steeped in “why” questions, why we were created, the telos of life. God as the original engineer isn’t threatened or confirmed by an Higgs boson. “The mind of God” that Einstein described will continue to be tested. This Nobel-worthy discovery simply reframes the “how” questions for the next generation of physicists. Prometheus is at its best when it suggests how many mysteries and wonders remain amidst the music of the spheres. It offers an intriguing “how” but dodges the “why” question.

In her hour of greatest need, David challenges Elizabeth to remove her ancient Christian symbol. She self-administers a harrowing c-section in an effort to kill the beast growing within her. For potential parents skittish towards pregnancy, this graphic depiction of an onscreen abortion may further reduce birth rates. But woman are strangely absent from the engineers’ universe. So how do they reproduce? The Genesis account of creation may blame Eve for humanity’s curse, but at least she offers an essential, complementary role in human flourishing. Prometheus puts women at war with the engineers and the aliens.

The story wobbles in the third act. Elizabeth’s invasive surgery may shred her abdomen but one shot of painkiller gets her back on her feet, severed muscles and all. Elizabeth survives a final encounter with a space jockey and a xenomorph. Yet, her closing reconciliation with David strained this viewers’ credulity (and resulted in audible guffaws from the audience). I understand that a robot may know more about biotechnology. But David ends up as a head in search of a heart (and body). Stephen Hawking summed up his scientific philosophy in sterile terms: “I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.” Yet, in Prometheus, artificial intelligence doesn’t have the moral framework to say, “Let’s get out of here.” Only a human like Elizabeth would press further, towards a sequel, despite all the warnings inherent in the story. Logic is helpful, but our hunger for meaning drives us onward, upward, outward.

Prometheus fills our heads with ideas, but ends up cut off from our hearts. The affirmation of faith at the end of the film suggests that humanity still desperately needs salvation. A Greek myth of overreaching has failed. Elizabeth takes up the cross again, renewing her Christian faith. Rather than cheering, I felt like seeking deliverance from this pseudo profound prequel. Prometheus aims to discuss the origins of life but ends up descending to the pulpy fiction of Chariots of the Gods.