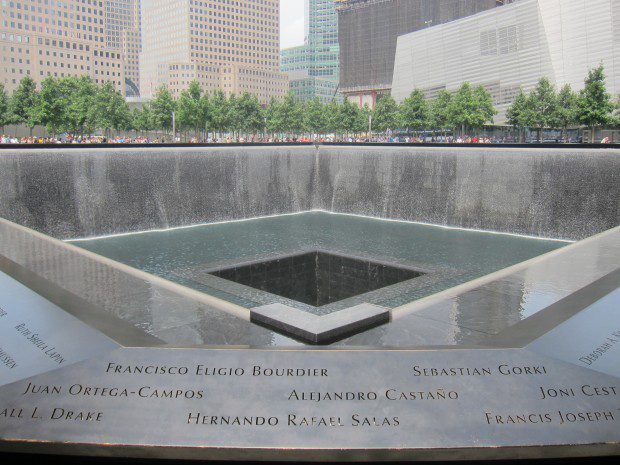

I visited the 9/11 Memorial in New York City over the summer. It is a peaceful place amidst the hubbub of Manhattan. Cascading water silences some of the din. The diversity in the names inscribed in the marble are a stirring tribute to the many peoples and tribes that constitute America. Two squares flowing with water mark the site of each of the twin towers. (Check out these 360 degree panorama views here). I was struck by how the water flows out from beneath the victims’ names before it takes a long, dramatic tumble. Most striking of all is the deep, dark hole at the center of the two memorials. It seemingly has no bottom. And perhaps that is appropriate given the depth of the sorrow generated by terrorism. While many monuments direct our vision upward, the 9/11 memorial pulls it down, into the ground. It is tough to create uplift from such a senseless act. It is even difficult to make heroes out of innocent victims who happened to work in the wrong building at the wrong time. A gaping hole forces us to stop, pause, consider.

Getting to the memorial is anything but peaceful. There is a long line to obtain free tickets meted out for timed entrances. Donations are collected beside the free tickets. A gauntlet that doubles the size of Disneyland lines snakes back and forth outside the memorial. Visitors pass through requisite security monitors, in some cases, a pat down or search may be required for entry. All of these reminders of the ongoing cost of 9/11 precede any effort to simply pause in respect for the dearly departed.

Eleven years on, we still struggle with ways to talk about the tragedy. We can cite heroism amongst police and firefighters who ascended the stairs to get people out of the burning buildings. We can salute soldiers who fell chasing agents of Al Qaeda across the Middle East. We can take comfort in the death of Bin Laden. But I sense that many soldiers and civilians are still wondering why we spent billions in Iraq and haven’t wrapped up a war in Afghanistan, our longest conflict in American history. We can vow to never forget–what it is like to be attacked, what sorrow and grief feels like, how sacrifices involves real costs and lives, but an air of ambivalence remains. And unfortunately, we have few ways of processing ambivalence in broad, public gestures. In writing this post and linking it on Facebook, I invite comments. And I also invite people to “like” my thoughts. But can our feelings around 9/11 ever be reduced to a “like” button?

Clicking on a “like” button is a form of voting, especially when it is aggregated around a pop cultural phenomenon like a band, a movie, or a team. The Dallas Cowboys, long revered as ‘America’s Team’ have over 5 million likes on Facebook, while the lowly Jacksonville Jaguars muster less than 300,000 likes. In the run up to the 2012 election, Barack Obama has over 28,000,000 people who liked him on Facebook. Mitt Romney had just over 6,000,000 likes. Perhaps such a significant gap amongst social media mavens will hurt Romney in the election. Yet, both Presidential candidates pale in their Facebook reach compared to Lady Gaga’s 53 million likes. What essentially became a point of self-identification, “Liking” a show like Glee or a singer like Bob Dylan (who releases new albums on 9/11) eventually morphed into a literal fanbase, a simple way to blast an update to millions of dedicated followers. “Like” moved from a show of support, to signing in for an electronic newsletters. But while we may “like” our troops serving overseas, we could never “like” 9/11. And I’m not sure we should even “like” the memorial. Admiration, sure. Appreciation, definitely.

What’s not to like about the “Like” button? It works splendidly when passing along pleasant news. But what happens when we’re sharing our pain or sorrow? We’ve all been confronted by status updates that might suggest dire circumstances such as, “Mom is in the hospital for an MRI, still waiting for a diagnosis” or “My Dad passed away today, getting in the car for long drive back to my hometown.” While such updates may trigger a wave of condolences, they are certainly not something we would “like”. And yet, Facebook doesn’t offer a ‘dislike’ button. This simple software choice may force us to rethink our status updates, shading them in hopeful terms. Slight shifts towards “Mom is in the hospital for an MRI, doctors working on a diagnosis” or “Dad passed away today, know he’s in a better place” make our updates much more “likeable.” While I am all for projecting hope, we must acknowledge that not all our prayers will be answered and not all of our experiences are positive. Facebook offers a way to reach out to friends and family, but it isn’t predisposed toward depression, doubt, or loneliness. I’ve seen updates that beg for a response, “Is anybody out there?” or “I’m so lonely” linger because they ask for a bit more than we may be used to offering via Facebook. A casual comment does not seem sufficient to enter into the conflicted feelings on the other end of the post.

The ‘like’ button may also limit the kinds of links we share. In his perceptive 2011 book, The Filter Bubble, Eli Pariser notes, “That Facebook chose Like, instead of, say, Important, is a small design decision with far-reaching consequences: The Stories that get the most attention on Facebook are the stories that get the most Likes, and the stories that get the most Likes are, well, more likeable.” It is much easier to pass along a funny video than a poignant news update. One generates plenty of likes, while the other forces a level of reflection and introspection that frankly, we may not ‘like.’ I could never “like” an article about genocides or floods or institutional injustice. I might find it timely, important, relevant, enlightening, but “like” seems too small an emotion to apply to complex issues that defy easy answers. By only offering an ability to “like” things, Facebook may inhibit our knowledge of wars, conflicts, and pressing social problems. Importance must be inscribed in the update itself—“An article worth thinking about” or even the ultimate abbreviated intro, “This: .” While it is certainly helpful to have a news feed that can sort through the world wide web and allow my friends to forward the best stories, we are also somewhat limited by the format itself. Facebook needs new buttons that offer a wider range of emotions. Facebook would still offer programmatic short cuts (perhaps offering three or four different emotional buttons to click). But users would also be invited to consider a wider range of sources.

So when it is time to reflect upon sobering moments and haunting realities, we can do far more than “like” an update. As the gaping hole at the center of Ground Zero reminds us, some things are beyond likes or even dislikes. They may even defy words.