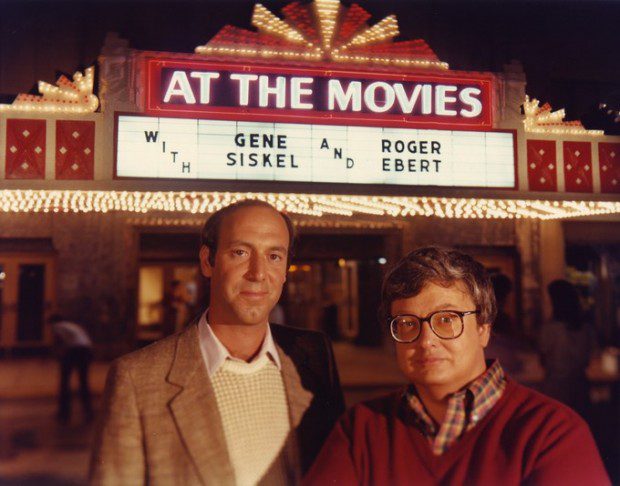

On the occasion of Roger Ebert’s funeral, I pause to offer two days of appreciation. My movie love preceded “Siskel & Ebert At the Movies,” but not by much. For my generation of film fans, they were the key critics at the right moment. Their weekly, televised reviews arrived in the eighties at the same time that so many classic movies arrived on home video. What had previously been the province of film societies suddenly opened up to a much broader audience. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert brought art house movies to the masses. They fervently believed in the transformative power of filmmaking for social change and spiritual uplift.

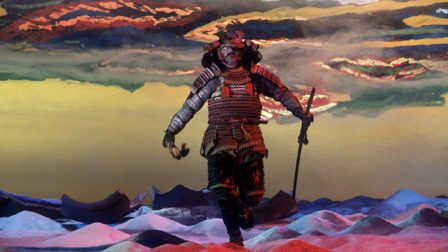

By setting our VCR to record “Sneak Previews” on PBS, we could find out about films that used to only be reviewed in The New York Times and The Village Voice. We could see clips of new releases from acclaimed international filmmakers like Terence Davies or Agnes Varda. It was as if lofty journals like Film Comment or Sight and Sound were being beamed into my living room, not just as magazines, but as a lived reality, available to teenagers like me in suburban North Carolina. Thanks to Siskel and Ebert, I sought out original films like My Dinner with Andre and Fitzcarraldo and the documentary Burden of Dreams (RIP to director, Les Blank who also just passed away). Siskel and Ebert introduced me to Akira Kurosawa, putting epics like Kagemusha and Ran on my radar. They made it cool to talk about films in passionate ways, to defend the cheesy and the artistic with equal aplomb.

If Gene’s Ivy League education veered him towards film snob, Roger’s University of Illinois background was much closer to today’s fan boys. Roger Ebert practically invented (or at least) articulated the passions of fan boys and girls around the world. Ebert defended the drive-in films that tapped into the Pulp Fiction that had always fueled the movies. He embraced unabashed genre films like Blood Simple and The Last Seduction, relishing their low-slung charms. Ebert also liked his films a little bit kinky from Bad Lieutenant to Exotica or The Cook, the Thief, his Wife & her Lover. Of course, how could the man who wrote the screenplay for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls have denied his guilty pleasures like Bound? Ebert always advocated adult movies about big ideas that dealt with sex and love in appropriately complex ways.

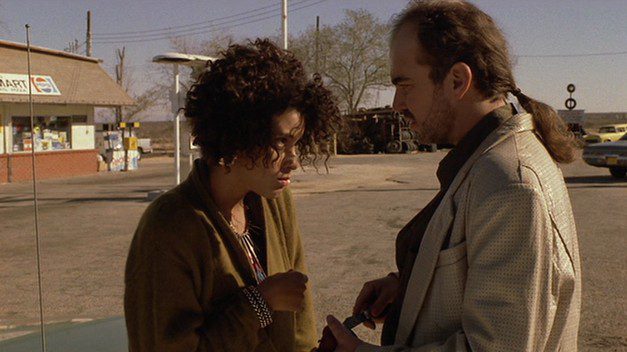

Ebert and Siskel lived out their liberal convictions by championing films that reflected the racial and economic divides in urban America. Their annual “Memos to the Academy” were aimed at broadening the Oscar voters’ purview. They shone a spotlight on key films that deserved much broader acceptance like Do the Right Thing, their top film of 1989. Siskel and Ebert also recognized how One False Move (1992) rose above low budget conventions to touch on important, enduring issues of race and responsibility. Their advocacy saved it from the direct-to-video bin (and launched Billy Bob Thornton’s career). We would never have dared to sit still for three hours of Hoop Dreams (1994) without their encouragement. This quintessential Chicago story took the long view of two young men who placed too much hope upon the basketball court. The Academy’s documentary branch still managed to ignore this landmark achievement (and prompted such ire from Siskel & Ebert’s fans that the Academy changed their nomination process). Ebert also championed Eve’s Bayou (1997), a fleeting moment when a black woman made a magical movie about black women that seemingly everybody paid attention to. Unfortunately that “Memo to the Academy Never Got through.” Ebert’s populist sensibility made my generation skeptical towards the Oscars.

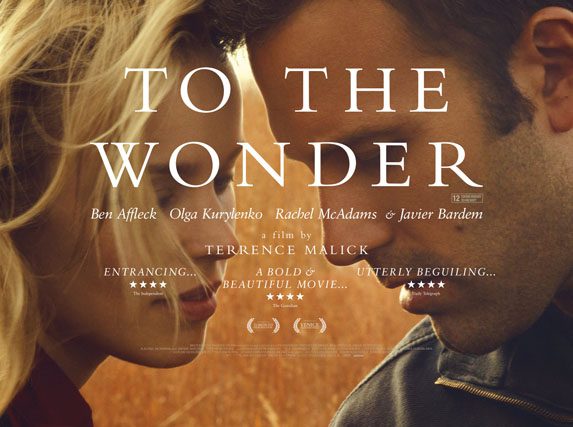

I am most grateful for his championing of the foreign and the obscure. How would I have found Kieslowski’s Three Colors trilogy or ten riveting hours of The Decalogue without Ebert’s introduction? I am so indebted to Ebert for turning me onto El Norte, Salaam Bombay!, Maborosi and Munyungarabo. These are smart, thick, important pictures. Without Ebert, I might have missed Paris, Texas or Wings of Desire. Where would my cinematic and spiritual life be without Wim Wenders’ insightful ennui? Ebert’s spiritual sensitivities drew him towards the simplicity of low budget, indie classics like George Washington and Man Push Cart. Ebert also reveled in the raw beauty of Terrence Malick’s radiant films from Days of Heaven through an instant masterpiece like The Tree of Life, placing it on his 2012 list of the top ten films of all time.

How fitting that Ebert’s final review is for Malick’s latest poetic meditation, To the Wonder. It is a majestic exploration of the meaning of life. It chronicles love and disappointment in beautiful ways. Ebert summarized it as “a few characters in search of transcendence.” To the Wonder has none of the giddy charms of the grindhouse. It is pure artistry, cinema as sacrament. You may be tempted to dismiss such a symphonic film, full of balletic flourishes. Malick and Ebert believe in the power of film to transport us, to lift us to a higher plane. I relish Ebert’s last review and urge us to honor his memory by being caught up in the heavenly vision of To the Wonder, opening this Friday.