To the Wonder aspires to nothing less than showing us Absolute Reality in the face of brokenness. It is a sun kissed paean to the power of love that unfolds at a maddening pace. Director Terrence Malick has made a ballet, a symphony, a kaleidoscope that harkens back to the glory and simplicity of silent film. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki captures luminescent moments. Five editors (!) were called upon to craft the free flowing improvisation into musical passages. It is cinematic symphony cut at a music video pace–utterly original and confounding. I’ve been struggling for two weeks to summon the words necessary to respond to the beguiling spell summoned by To the Wonder. It veers so close to inscrutable, before offering us a taste of the eternal.

It is also so simple as to be frustrating. The plot driven viewer will wonder why Ben Affleck doesn’t say anything for the first fifteen minutes of the film. He is onscreen, but he is a cipher; or at most, a dramatic foil upon which hopes and dreams of eternal love are projected.

To the Wonder is about the sheer beauty of love, how it flows in at unexpected times. It sweeps us up, in a rapturous embrace that makes us want to dance through the aisles at the supermarket like Olga Kurylenko, a Ukranian Bond girl, cast here as Woman (Marina), falling for Ben Affleck, our biggest movie star, a k a Man (Neil). Ben Affleck may be America’s biggest movie star. Not the best actor, not the tops in box office, but the biggest hulking mass of a movie star we’ve got. Way bigger and taller than his rivals like tiny Tom Cruise. Poor tiny Tom would be swallowed up by the landscapes that surround Big Ben and his Bond Girl. They are given almost nothing to do other than to stare at each other in delight and glance away in disappointment. Because at the end of the day, what else is domestic life but a series of drawing near and falling apart. We are bonded by commitment that survives shifts in feeling or crushed by the ideals that cannot be maintained. First love flits about Paris. Mature love endures winter in Oklahoma.

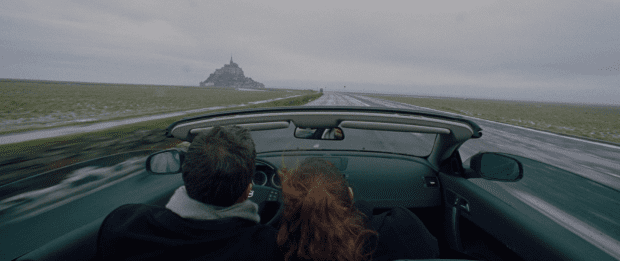

The most captivating moments of To the Wonder occur in that first flush of love, when everything seems to be spinning. Marina and Neil find each other in Paris, the most romantic city and run away to Mont Saint-Michel, the most majestic and mystical setting in France. The moment when we’re whisked into their convertible approaching the Wonder (La Merveille) that is Mont Saint-Michel, is the most exhilarating cut in the movie. The sequence where the water recedes and returns, threatening to cover the lovers (and us) is deliriously beautiful and intoxicating.

Alas, rapture rarely lasts. Try as we might to bottle it, preserve it, sell it at Victoria’s Secret in the mall, it fades. Or morphs into something else, resembling domesticity. France blurs into Oklahoma which has it owns severe beauty. The American heartland features the beauty of almost nothingness. Bartlesville, Oklahoma offers a stark horizon, fields of grain, and a sunset each and everyday. But it proves harder to see the wonder when you’re trapped in suburbia. A foreigner can remind us what is marvelous about America: our cattle, our open spaces, our democratic ideals like parades through downtown.

Our efforts to bottle that, to exploit those amber waves of grain, are doomed to failure. Ben Affleck plays some kind of environmental activist. He measures the water, takes samples from the ground, searching for contamination, but he doesn’t seem to be very good at measuring his own household for contamination. He can’t seem to keep his French beauty satisfied. Her ten-year-old daughter fails to adapt. The high school band and football stadium aren’t her scene. And the daughter exits the stage, back to Daddy in France.

The wonder returns when Big Ben comes across his old high school flame played by Rachel McAdams. She has a ranch, a big family ranch that could use a large man like Big Ben Affleck to tend it. Their date amongst the buffalo is amongst the most wondrous sequences in cinematic history. We are invited to linger, to feels what it is like to have a home where the buffalo roam. The deer and the antelope are implied.

You want it to work out for Ben and Rachel (called Neil and Jane). They run, they play, they frolic with such homespun abandon.

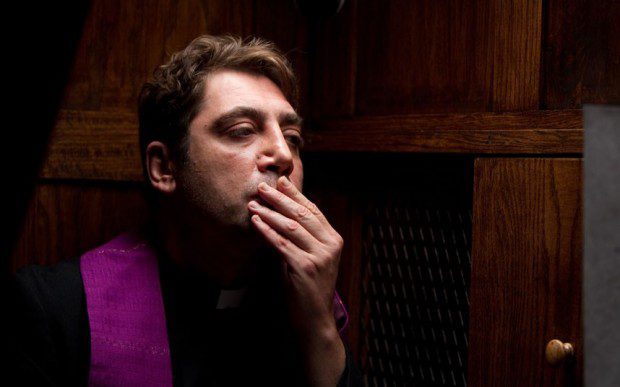

Despite our hunger for happiness, all the characters in To the Wonder seem caught in a cycle of self-sabotage. Contentment eludes us. This is why we need a priest; to frames things, to explain things, to get us through a really crappy week or season. Javier Bardem adds yet another accent to a film filled with the inflections that cover the globe. He is Father Quintana, serving in suburban Oklahoma, standing in for Every priest. He suffers inside while dispensing the sacraments.

He goes door to door in Bartlesville, encountering the working class in all their uneducated glory. What they lack in healthcare or dentistry is counterbalanced by a dose of wisdom. They see the fragileness of life, they long for the simple comfort of a hug, a prayer, the heavenly host.

To the Wonder will frustrate most viewers because it doesn’t really go anywhere. A European beauty attempts a trust fall. An American hero catches her, but even with a green card, she still wants more. Her friends may even encourage her to have an affair. We all know how stupid infidelity can be, despite the allure of forbidden love. Nobody gets what they want (including viewers).

So why did Terrence Malick make this rapturously beautiful and frustrating movie? To the Wonder is a deeply personal follow up to his deeply personal masterpiece, The Tree of Life. In Tree of Life, Malick mined his childhood, and the problem of pain caused by the death of his brother, to tackle universal truths about suffering. The Tree of Life took us from the Big Bang and the Garden of Eden through the Book of Job, and to the River Jordan. It covered birth, death, eternity. To the Wonder draws upon Malick’s romantic misadventures, from his second marriage to a French woman and his lost years in Paris to his return to America and his third marriage to his high school sweetheart, Alexandra Wallace. His failings serve as a jumping off point for the universal frustration we all feel with this love that almost never lasts. To the Wonder is the middle film of a trilogy, slated to conclude with Christian Bale starring in Knight of Cups. We may not fully grasp To the Wonder until we see how all three films fit together.

How are we supposed to receive a film that is created via improv and offered as a sacramental gift? As an organ prelude prepares our spirit to enter into worship at within a cathedral, so Malick’s films require us to set aside the hurried pace that we normally bring the cinema. He doesn’t want us to get amped up, but rather chilled out. Malick is the anti-Tarantino. He eschews interviews, withdraws from the press, and withholds his presence. Quentin Tarantino we cannot avoid. He forces his way into his own films even to their detriment. From Reservoir Dogs to Django Unchaimed, he hammers us with cruelty we’d like to escape. He purges us of our sins with literal bloodlettings. Malick’s movies are as beautiful as Tarantino’s are ugly. But Malick doesn’t come at us. He lulls us in with beauty. Then, he makes us do the work. He doesn’t tell us what to think. He doesn’t twist us up in character or plot. He just unspools a world of wonder and delight, everyday glory that is available for all to access; if we choose.

While millions flock to Tarantino’s ritual floggings, we avoid the poetic pauses of Malick like the plague. A little complexity, in the shifting timeline of Pulp Fiction or in the will-the-Nazis-get-what-they-deserve, Inglourious Basterds kind of way, equals box office gold. Genuine complexity, in Malick’s can’t-be-summarized-by-a-capsule-review kind of way, is box office poison.

While Tarantino is rewarded for beating us up, Malick is avoided for breaking us down. His movies strip away our longing for the quick, the convenient, and the tidy. He gives us so many beauty shots that we can’t take any more. Who knew that sunsets could be so boring! What is on the other side of the looks, the gestures, the light, and the shadows? (Spoiler alert!) To the Wonder concludes with the most unapologetic explication of Holy Communion ever captured on film.

A frustrating film about frustrated lovers who cannot find peace or happiness concludes with an unabashed celebration of the Mass. With his marriage on the rocks, Ben Affleck is invited to ride along with the priest, to see what service and sacrifice looks like. As the priest dispenses comfort to the hungry, the hurting, and the bereaved, we are invited to receive the gift of life. The answer to life’s pain and problems is quite specific: “Christ be with me. Christ before me. Christ behind me. Christ in me. Christ beneath me. Christ above me. Christ on my right. Christ on my left. Christ in my heart.” As with the equally specific heavenly vision summoned in The Tree of Life, this gracious conclusion of To the Wonder made me weep. I was probably a minute or two away from walking out, giving up, fleeing for something tidy. I endured just enough frustrating beauty and bad decision making to receive the gift of life. To the Wonder ends with a prayer, a psalm of ultimate, universal longing: “Thirsty. We thirst. Flood our souls with your spirit and life so completely that our lives may only be a reflection of you. Shine through us. Show us how to seek you. We were made to see you.”

Malick offers fleeting glimpses of God—during hopscotch in the shadows of a window, in rollercoaster rides at the carnival, in the tide rolling in. As with Jesus’ confounding teaching, these moments are offered without a hook or catch for those who have eyes to see.