There has been plenty of heat generated by the jury’s verdict in the George Zimmerman trial. I have read so many heartfelt responses and blog posts in an effort to understand what transpired. Some have been more helpful and insightful than others. With the Florida jurors now chiming in, Trayvon Martin’s shortened life may be buried under the rush for television ratings. That is why Fruitvale Station is such a timely and important movie. It allows us to step into the shoes of another young black man whose life was also cut short by a bullet. It is a rehumanizing experience arriving in a highly politicized moment.

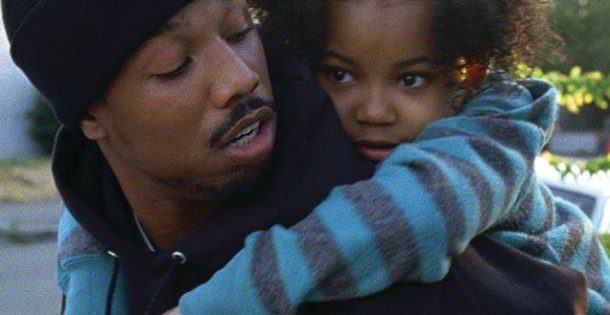

By recounting the murder of Oscar Grant III by a Bay Area Rapid Transit officer on New Year’s Day 2009, Fruitvale Station reminds us how familiar, repetitive and tragic Trayvon Martin’s death remains regardless of where you stand on ‘stand your ground’ laws. It puts a highly memorable face to yet another homicide, turning a statistic into a father, a son, and a brother. It resists the temptation to make Oscar into a saint. He was an unmarried father and a part-time drug dealer with a criminal record who deserved much more than a shot in the back. Fruitvale Station shows how fragile and expendable we continue to make African-American men. They vacillate between the tragic poles of “invisible man” and “suspect/target/victim.” Fruitvale Station is a poignant plea for healing, a deeply felt, highly personal film about how much every life matters.

Fruitvale Station is a remarkably assured first feature from Ryan Coogler, a young USC film school grad who recognized his similarities to Oscar. It is an Oakland story told from an Oakland perspective. In chronicling Oscar’s last day, Coogler has wisely avoided hyperbole, concentrating upon the ordinary and mundane. Oscar is trying to figure out how to pay rent, how to be a good father, where to find a job that will earn enough for him to get married. His love for his girlfriend, his daughter, and his mother is clear. But the odds stacked against a young man with a prison record and a short fuse are also clear.

A few flashbacks and moments of introspection demonstrate the tenuous nature of Oscar’s situation. He could sell reefer to make ends meet. He could end up back in jail, fighting for his life on the prison block. Even talking on his cell phone while driving could cause a downward spiral. On New Year’s Eve, Oscar meets an Anglo businessman in San Francisco whose criminal actions didn’t disqualify him from the American dream. But the political overtones are rooted in character rather than speeches. This isn’t a loud film like Boyz ‘n the Hood or Menace II Society. It is a much gentler cry from a new generation still searching for sustainable alternatives.

Some have criticized Fruitvale Station’s most dramatic flight of fiction. Coogler introduces a dog whose life is equally expendable. Obvious parallels are drawn: Oscar will be mowed down in the streets before he reaches maturity and potential. So many have been lost without justice, trial, or a second chance. The hopes of girlfriends and daughters are not fulfilled. The fervent prayers of God-fearing mothers are not answered. Fruitvale Station is a cinematic theodicy that answers the question, “Who is my neighbor?”

Perhaps the most memorable scenes convey the easy camaraderie and genuine love within Oscar’s family. Grandma’s crab gumbo brings them together for birthdays and holidays. Irrespective of how one feels about the George Zimmerman trial, Fruitvale Station serves as a stirring reminder that grief continues to haunt the Martin family. Perhaps the jury made the right decision based upon the evidence, instructions, and laws handed down to them. But the verdict stings because it is yet another blow in a long, painful history of (in)actions that consistently devalue African-American males, especially those in our inner cities who are regularly stopped for “Driving While Black.” Those of us in positions of privilege and power have rarely felt what is it like when people cross the road to avoid us on the sidewalk or when passengers in an elevator clutch their purse when we enter. We haven’t been considered suspect simply because of the color of our skin. This ninety minute movie is a rare opportunity to experience the madness and injustice of racial profiling.

I befriended so many young men like Oscar and Trayvon while I was working for Urban Young Life (twenty years ago). I played basketball (poorly) in some of the toughest sections of Charlotte, North Carolina. I was never scared for my safety, but for theirs. They knew how quickly their lives could be snuffed out without many repercussions. Their dreams rarely went much further than making it to age eighteen and maybe graduating from high school. They were plenty smart, very creative, full of potential. But they could rarely see beyond the situation they found themselves in; lousy schools, limited role models, and scant financial support. My heart broke for them on a regular basis. The cycle felt so much larger than any of our best efforts to rise above. Black on black violence continues because we’ve consistently communicated how little these young men are worth to our society.

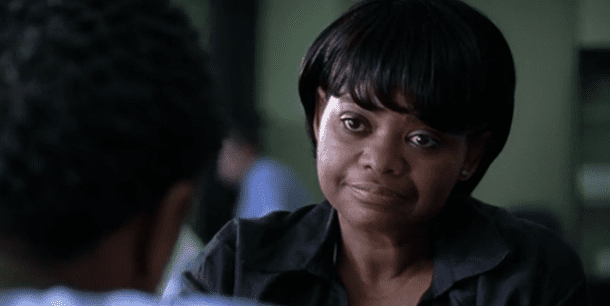

Fruitvale Station shows how a few random moments pushed Oscar Grant from life to death. The climatic moment on the train felt a little too dramatically contrived. But the police brutality played all too real. The audience in our theater gasped at the sight of a bullet hole in his back. For once, the movies made us consider the human cost of gun violence. Thanks to the powerful performances of Michael B. Jordan, Melonie Diaz, Sophina, Ariana Neal, and Octavia Spencer, we walk more than a mile in Oscar’s shoes. We are offered the profound gift of empathy. It shouldn’t take a movie to make us mourn. But if it makes us feel more than a headline and potentially reorient our laws, our education, and our economics in more equitable ways, then Fruitvale Station will have earned far more than accolades at Sundance and Cannes. We discover how little (and how much) separates Oscar and Trayvon from us.