I hosted a screening of Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom just two nights before Nelson Mandela died. The legacy of Mandiba was already in the forefront of my mind before the news of his passing. It will be tough to ever separate the movie (and its Christmas release) from the timing of his death. Audience interest in Idris Elba as Mandela will widen following his funeral in South Africa. The resulting box office and Oscar boost for the Weinstein Company will be considerable. Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom arrives at a teachable moment, serving as a timely cinematic eulogy for an extraordinary life. Mandela’s courage is placed alongside his indiscretions, celebrating his humanity rather than just hagiography.

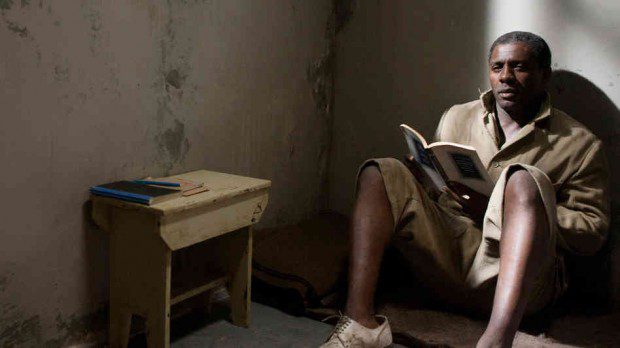

The danger in every biopic aspiring to definitive status is that it will skim the surface, hitting only the highlights. While the facts may be rendered factually and chronologically, the picture may fail to convey the inner life behind the headlines. Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom does race through the early years of a remote village upbringing through his rapid rise as a young lawyer in Johannesburg. We see events without necessarily understanding their importance. Only as the action slows down, with Mandela in prison, do we start to appreciate the depth of his character. As he changes, our engagement rises. We see how essential the struggle becomes. As Mandela grasps his purpose, we grow in our understanding as well.

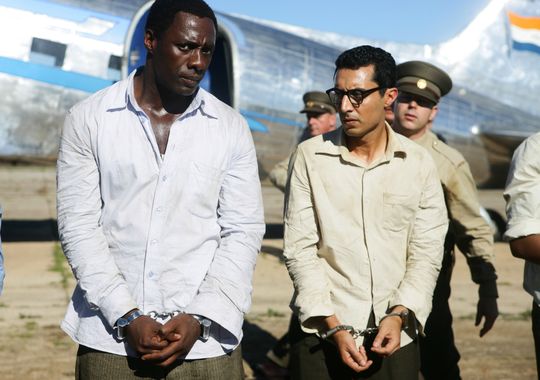

The filmmakers’ attention to detail, recreating the apartheid era in South Africa, is uniformly excellent. While Idris Elba may not resemble Mandela, he captures the intensity that fuels Madiba’s resistance. It doesn’t take many Sharpeville massacres to understand why Mandela and the African National Congress shifted from non-violence to bombmaking. The bigger mystery is how Mandela managed to forgive those who locked him up and decimated his family and community.

Mandela the movie portrays Mandela the man as fallible and powerful, a firebrand who revels in negotiating his way out of prison and towards equality in South Africa. It is remarkable to consider the historic shifts Mandela witnessed (and initiated in his lifetime). We see how he moved from young lawyer to ANC activist to taking up arms. His womanizing costs him a first marriage. The bombings send him to prison. We feel the high personal cost of imprisonment on Robben Island to both Mandela and his second wife, Winnie. Remarkably, his authority grows while he is incarcerated as events beyond the prison walls bring South Africa to a crisis point.

While we expect a masterful performance from Idris Elba as Nelson, it is the steely resolve of Naomie Harris as Winnie that makes the story work. The rage and bitterness that grows in Winnie’s heart during her husband’s imprisonment becomes a strong counterpoint to his comparative grace. Their monitored conversations in prison carry such weight. As she raises their daughters alone, we understand why she would push back against every police search and interrogation. Her time in solitary confinement only deepens her commitment to armed resistance. The radicalization of Winnie makes sense.

What is far more surprising and underexplored is Nelson Mandela’s ability to forgive. How does he summon the patience to negotiate with those who have jailed him? How can he approach secret meetings with Dutch South Africans with such a calm demeanor? Scenes of Mandela dressed in a new suit form such a contrast with the hard labor that he faced in prison. His cagey negotiating style earns some of the only laughter in an appropriately serious film. Perhaps the primary weaknesses in Mandela the movie is that we are never privy to the engine that drives his strength to forgive. While his comrades heighten their commitment to resistance, Mandela sees a compromising way forward. What eyes of faith informed such a transformation? We are left to wonder. The film never connects Mandela’s Christian roots to his ethics or practices.

Perhaps another film remains to be made about the faith and wisdom of Nelson Mandela. Long Walk to Freedom is a moving introduction. It reminds us how much we may have forgotten or never heard about his life, about South African history, about the key crossroads in their overlapping stories. It should spur us towards films that go into greater detail about his transition from prison to President, like the 1997 portrayal of Mandela and de Klerk by Sidney Poitier and Michael Caine. Those intrigued by Nelson’s relationship to his prison guard will find much more in Goodbye Bafana starring Dennis Haysbert and Joseph Fiennes. So much archival footage was gathered for the official, Mandela approved, 1996 documentary. Historians will have ample material to place in context.

In the meantime, I came away from Mandela the movie marveling at how much change we all may experience in our lifetimes. It may not be as radical as prisoner to president, but the overturning of apartheid will look rather swift in the annals of history. A racist policy of separation was resisted from within and without South Africa. May those who seek to separate us along racial, cultural, or economic lines continue to encounter resistance. Thanks to the powerful words and witness of Nelson Mandela, we know that radical change remains possible. Truth and reconciliation are an elusive goal ever worth pursuing.