After Son of God, Noah, and God’s Not Dead demonstrated strong box office appeal, the media has dubbed 2014 as “The Year of the Biblical Epic.” Stories in the Los Angeles Times, Fox News, NPR, The Daily Beast, U.S. News and World Report and The Telegraph have chronicled this ‘flood’ of faith fueled films. Another religiously themed movie opens this week: Randall Wallace’s stirring adaptation of the bestseller, Heaven is For Real. Later this year, Christian Bale will take on the mantle of Moses in Ridley Scott’s retelling of Exodus. As I recently said on PBS’s Religion & Ethics’ News Weekly, when the movies “go big,” they often go biblical.

As we head into Holy Week, I thought it appropriate to survey the checkered history of the biblical epic, especially the oft told story of the life of Christ. Forget James Bond or Spiderman: the Son of Man has been the focus of far more cinematic adaptations and remakes (with very mixed results!). From Pathe’s depiction of The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ (1902) to Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), filmmakers’ attempts to encapsulate the life of Christ have inspired Christians while also raising concerns about anti-Semitism. Too many depictions of the Last Supper have failed to remind viewers that Jesus was first and foremost, a Jew, observing Passover. Artistic choices and interpretations often reflect the spirit of the age. Perhaps by looking across cinematic history, we can transcend some of our own cultural blinders and come to a deeper understanding of what Jesus meant and means.

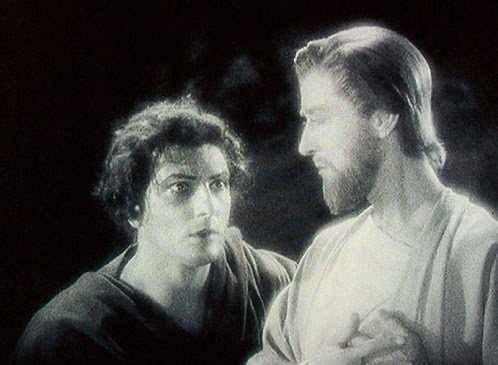

The grandest silent “Jesus film” is Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927). H.B. Warner portrays Jesus with strength and confidence, but DeMille takes liberties with the biblical narrative, creating a love triangle between Mary, Judas and Jesus. He blends sex and spirituality, as a scantily clad Mary Magdalene dances across the screen. The eerie special effects of King of Kings have held up over time as when seven deadly sins exit Mary’s body.

Jesus became an almost otherworldly figure in the fifties, depicted with such reverence that only the back of his head could be revealed in The Robe (1953) and Ben-Hur (1959). These widescreen epics attracted massive box office, reaching their apotheosis in King of Kings (1961) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1966). The sincerity in such movies can be stifling as Hollywood stars make distracting cameos. John Wayne’s appearance as the Roman soldier stationed at the foot of the Christ nearly killed the biblical epic.

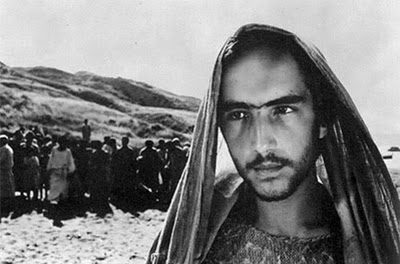

As theology wrestled with “The death of God” movement, so filmmakers began their quest for the historical Jesus. Pier Paulo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1966) is widely regarded as the most authentic and moving life of Christ on film. By casting non-professional actors from a remote Italian village, Pasolini brought grit to the gospels often lacking in more extravagant features. In St. Matthew, Jesus is a man of the people, serving the poor, challenging the authorities. As a gay man with Marxist leanings, Pasolini highlighted Jesus’ solidarity with those outside the corridors of power. How does one seemingly beyond church borders create such a compelling portrait of Christ? Perhaps artistic distance creates a fresh perspective.

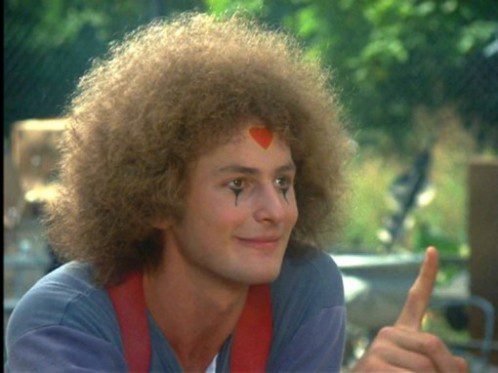

The foment arising in the 1960s resulted in vibrant re-imaginations of the life of Christ. From Broadway musicals came Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) and Godspell (1973). Both use rock music to place Jesus’ loyalties with hippies and flower children. While Jesus Christ Superstar retains a Middle Eastern setting, Godspell brings the Bible to New York City. Jesus becomes a holy fool, a clown, sporting a Superman logo and suspenders. These groovy time capsules made Christianity relevant in a turbulent era.

The ‘demythologizing’ of the Bible occurring in academic circles led to several cinematic controversies. Christians protested the release of Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) and Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Both films generated more headlines than ticket sales. As a comedic satire, The Life of Brian demonstrated how cults are born out of disinformation. The film respected Jesus but mocked how crowds clamor for miracles and form faction around thin premises. Many Christians failed to find the humor in the wacky chorus that accompanied the crucifixion: “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

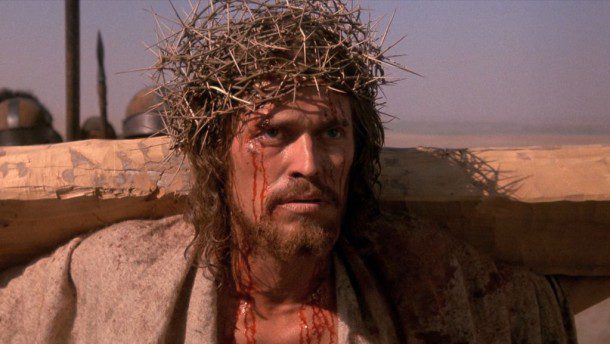

The charges of blasphemy reached a fever pitch with The Last Temptation of Christ. While director Martin Scorsese described the film as an act of devotion, outspoken Christian leaders denounced it as an abomination. Audiences failed to distinguish between the Gospel accounts of Jesus and the film’s source material: a novel by Nikos Kazantzakis. Scorsese depicts Jesus’ temptation to eschew the cross for a life of domestic bliss as a dream. The courageous faith affirmed at the conclusion of the film was lost amidst the double-minded portrait of Jesus that preceded it.

Jesus of Montreal (1989) offers a brilliant commentary on the domestication of Jesus. It places the passion narrative within a Canadian theatre troupe. A dwindling church eager to attract a crowd at Easter commissions a desperate actor to update the Passion play. The church authorities in Montreal are too busy putting on a show to notice the shocking parallels to the crucifixion unfolding in their midst.

The bloody Jesus depicted in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) generated so much press. Gibson responded to the charges of anti-Semitism with defiance, creating huge anticipation for his privately financed act of devotion. With a script in Aramaic, The Passion did not court mass audiences. Yet, this small movie, shot in the same village as The Gospel According to St. Matthew, became an international sensation. Love it or hate it, the public rushed to see it. Mel Gibson made the crucifixion front-page news. Only in years to come, after the passion around the movie subsides, will we be able to judge whether it is a parade of horrors or a work of profound beauty (or a bit of both!).

Few filmmakers dared to combine Christ and cinema since then. Two films released in 2006 cast Jesus as a black man. The Colors of the Cross connected Jesus’ persecution to the struggles of people of color. Son of Man places Jesus in a contemporary South African context. Mark Burnett and Roma Downey are to be commended for daring to bring Jesus back to the big screen, especially under the bold title, Son of God. Almost every attempt to adapt the life of Christ to the big screen has faced some resistance. Yet, we can be confident that the radical and sacrificial life of Christ will continue to inspire the next generation of storytellers (and audiences!).

So which Jesus film do you find most compelling?