In our last Neo-Pascalian conversation, I indicated that fragment 418 held yet another clue to the business of make-believe faith. There he addresses the one who “seeks a cure”—who recognizes his or her unbelief and wants to remedy the situation. That, I suggested, indicates the all-important role of desire. If you recognize that you are in a state of unbelief and you couldn’t care less, there’s nothing that can be done for you, humanly speaking. (Though, of course, with God, all things are possible.) But if you recognize that you are in a state of unbelief and that troubles you or creates some inner turbulence, then you have hope.

In our last Neo-Pascalian conversation, I indicated that fragment 418 held yet another clue to the business of make-believe faith. There he addresses the one who “seeks a cure”—who recognizes his or her unbelief and wants to remedy the situation. That, I suggested, indicates the all-important role of desire. If you recognize that you are in a state of unbelief and you couldn’t care less, there’s nothing that can be done for you, humanly speaking. (Though, of course, with God, all things are possible.) But if you recognize that you are in a state of unbelief and that troubles you or creates some inner turbulence, then you have hope.

Think of that inner unrest as a smoking ember. Far short of fire, still it eats away at your soul, waiting either to be fanned into flame or to be extinguished, snuffed out in an unobserved silence. If you can name that unsatisfied longing and make even the smallest wish that faith would come to you, would ignite your soul, would kindle holy fire, then that is where you must begin.

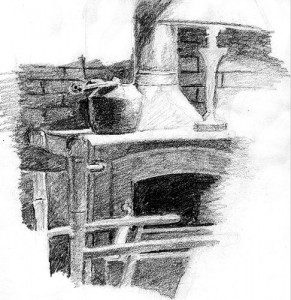

At the center of our family’s favorite mountain cabin retreat sits a hefty woodstove. Since it’s the only source of heat in that cabin and sometimes I’ve been up there alone, even I have learned how to build a fire in it. Building a good fire can be an all-consuming task, and when it’s really cold outside, it’s not only all-consuming, it’s urgent. Bundled and mittened, booted and scarved, I put a few logs in a little stack, wad up newspaper and stick it under and around the wood, and light the edges with a match or two. Then there’s the “fire dance”—carefully adjusting wood and air, opening and closing vents, cracking the door, sometimes adding more paper, adjusting the logs, poking, peering, prodding, shuffling all the ingredients until a raging flame has taken over the work.

What am I doing here? I’m “cooking” a fire, adding and stirring and seasoning and tending the flame.

Our desire for faith becomes holy desire and kindled faith when we approach the process in much the same way. Or so suggests Pascal. Look again at this part of fragment 418:

…at least get it into your head that, if you are unable to believe, it is because of your passions, since reason impels you to believe and yet you cannot do so. Concentrate then not on convincing yourself by multiplying proofs of God’s existence but by diminishing your passions. You want to find faith and you do not know the road. You want to be cured of unbelief and you ask for the remedy: learn from those who were once bound like you and who now wager all they have…

All too often we tackle the problem of unbelief (that is, if we even think of it as a problem) head-on. We look for, and sometimes concoct, “proofs of God’s existence.” And while I wholeheartedly endorse the great work of apologetics, I humbly suggest that apologetics alone—evidence that elicits the right “verdict”—cannot generate faith. Cannot generate faith.

So much evidence, so little faith. Surely that is what Our Lord himself must have thought and felt so much of the time. “Give us a sign!” they whined. “Show us something indisputable.” Okay, how about healing a paralyzed man? Feeding thousands on a few loaves of bread? Walking on water? No, none of that is evidence enough? How about raising the dead? No? What then?

Of course, we who live 2000 years after the fact may dispute this evidence by questioning the accounts: who wrote them, when, why, to what purpose? How historical? How accurate? Blah, blah, blah. But behind all that we must simply recognize that all the evidence in the world, right up close, in their face, did not generate faith among so many of those whom Jesus met and loved and taught. All our clamor today for evidence is beside the point because we could “multiply proofs” until we’re blue in the face and still not have faith.

Pascalian spirituality bids us move beyond multiplied proofs to the place of desire. Are you cold and in need of a blazing fire? Then feed the fire. Make it a matter of urgency, of first importance. Do not neglect the longing in your heart. Do not let it go out in a small, unobserved puff of neglect. Pascal encourages us thus:

I can feel nothing but compassion for those who sincerely lament their doubt, who regard it as the ultimate misfortune, and who, sparing no effort to escape from it, make their search their principal and most serious business. . . . There are only two classes of persons who can be called reasonable: those who serve God with all their heart because they know him and those who seek him with all their heart because they do not know him. (f. 427)

There are so many, many ways to not seek God, so many opportunities to quench desire. A vast array of other choices awaits you. These are “the passions” Pascal mentions: “if you are unable to believe, it is because of your passions … diminish your passions.” Pascal is not talking about asceticism—the stripping away of all pleasures and natural human activities for the sake of some grim, austere, barebones life. Pascal is no dualist, who might argue that the flesh, with all its material complications, is an evil weight dragging the more worthy spirit under waves of condemnation. Remember who we’re talking about here—Pascal is a scientist, a man who understands and appreciates the glories and wonders of the created order and who wholeheartedly believes in the great and godly role of reason in all we do.

When Pascal talks about diminishing passions, he is talking about those ever-present opportunities to satisfy our desires in another way. These don’t have to be intrinsically sinful activities. Distracting passions include a wide variety of seemingly innocuous addictions—from shopping to excessive internet browsing to video games to hours of television to … Well, you can name just as many as I can. We are impatient and ravenous in our desires, and the idea of having to actually feed hunger—that is, let it build rather than satiate it—is repellent to our souls.

I actually still get a newspaper, and one of the comic strips I follow is Zits, by Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman. It’s about a gangly teenage boy, Jeremy, and his friends and parents. Sometime earlier this spring, the strip showed Jeremy, who’s always in the Neanderthal position (i.e., slumped over with arms hanging loose), walking into the kitchen. His dad is at the stove, clearly cooking. Jeremy stands behind him, waits a moment, and then asks, “How long until dinner?” The dad answers, “Oh about thirty seconds.” And Jeremy responds: “Do you mind if I make myself a snack while I’m waiting?”

How painfully true this is … of me! I want what I want when I want it. And sometimes I cannot bear the emptiness or the darkness or the hunger, and though it speaks to me of the One who alone can fill and enlighten and satisfy, I snatch up something else that can put off or cover up that yearning.

And yet, the spark of longing, the simple little prayer—“incline my heart”—needs tending. How can we keep the prayer alive?

Next time we’ll outline the four most basic acts of “tending the fire.”

Photo courtesy Dave Kleinschmidt, Flickr C.C.

___________________

Note to Reader: This series on Becoming Neo-Pascalian considers some of the ways Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) speaks into the 21st century. It draws from my own research, published in Beyond the Contingent (2011), and citations are from the book, unless otherwise noted. The beginning of the series is here: Introduction.