As a nine-year-old, living in a different state from my Papa, I was fairly unmindful of him; he was more mythic than substantial. Even my memories of him are blurred around the edges, only coming into focus when I look at photographs of him. Tall, lanky, small wire-framed glasses, an ever-present pipe with that sweet smoky smell. A fisherman, a hunter. A tiny house in Springfield, Illinois, a cluttered living room, a round rack for an absolutely fascinating collection of pipes; rare and rather edgy visits since his abrupt remarriage to a woman the family disapproved of.

As a nine-year-old, living in a different state from my Papa, I was fairly unmindful of him; he was more mythic than substantial. Even my memories of him are blurred around the edges, only coming into focus when I look at photographs of him. Tall, lanky, small wire-framed glasses, an ever-present pipe with that sweet smoky smell. A fisherman, a hunter. A tiny house in Springfield, Illinois, a cluttered living room, a round rack for an absolutely fascinating collection of pipes; rare and rather edgy visits since his abrupt remarriage to a woman the family disapproved of.

I remember my mother’s grief more than anything. It was my first funeral. There in the church we sat through the funeral, of which I remember nearly nothing except my mother sobbing for her father. A parent’s tears are always wrenching to a child, but then she did something completely out of character…as much as I could understand her character at that point in my life.

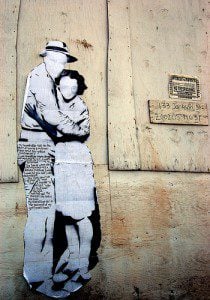

There was a railing between the pews and the front of the church, the coffin on the far side, us in the front row. After the service was over, before they could wheel the casket out, my mother went up to her dad’s coffin and draped herself over it, weeping with abandon. This was unlike my mother. Even now I wonder, did I imagine such a thing? My mother? with such a display of emotion and lack of restraint?

My memories of Papa’s funeral are all shot through with a sea change in my own awareness. I came to realize that my mother, who in my childish narcissism I had thought of as an orbiting moon around the sun that was me, had a secret life. An inner life. A world of thoughts and emotions and memories that had nothing at all to do with me. I was sad that my Papa had died, but I did not particularly share her grief, and the fact that she so loved this man that I barely knew kindled a new level of alertness in me; it awakened me somehow to a non-me-centered existence. The sorrow and the plain love had a story that was before and beyond me. Both my mother and my Papa came alive to me in new ways…at his funeral.

Later, much later, I found out new and curious things about my Papa. That Edgar Guest was his favorite poet; that he struggled to stay employed as a store manager during the Depression; that he may or may not have known his wife had an abortion because of their desperate poverty; that he really loved his two children; that his faith was a very private matter; that he loved to bowl, much to the chagrin of his wife who believed that dark bowling alley was a pit of degradation. Even these details are cursory and ever-so-small pieces of confetti in a rich life. As “outside” of my 21st-century reality as all these early to mid-20th-century details are, they still shape me and remain as symbols, untranslated perhaps, of truths that make me me.

Last week in church we read the story of the raising of the widow’s son in Nain (Lk. 7.11-17). As our pastor pointed out, the dead man is really just a prop in the story. The real action is Jesus’ response to the widow’s grief. He sees her sorrow and has compassion on her. Not on the dead man. On the mother. Restoring her son clearly made Jesus happy. The two—mother and son—now had a future together. They also had new identities: the Woman Whose Son Was Raised from the Dead and the Boy Who Was Returned to His Mother. I’m sure the stories were told in their village for years afterward … and of course are even now told in our churches. Clearly it was a transformational moment for them both, in more ways than one. The web of their lives together was both restored and enhanced, changing them, their communities, their stories, their futures. The son’s funeral became the awakening event of their lives.

Sometimes celebrating our fathers and grandfathers means not only treasuring the dearness of our relationships with them and the memories of those relationships, but standing back far enough to appreciate the depth and complexity of their lives, their loves, their experiences, their sorrows, their memories. The intricate mesh of our lives means that grandpas—even the ones who didn’t live long enough to embed themselves in our love or, perhaps, even the ones who lived too long and embedded themselves instead in our woundedness—are spinning globes wielding magnetic pulls on the lives around us, even long after they are gone. Their blessings and brokenness, passions and struggles, their sleepless nights and greatest joys, their fierce anger or helpless grief or tenderest moments—they tug at me in strange, unspoken ways.

A mysterious intergalactic photonic entanglement. A mystical interrelational entanglement of love and loss, life and identity; both a receiving and a letting go at the same time.

Photo courtesy taberandrew, Flickr C.C.